Searching for your ancestors teaches you a lot.

When you start to see past the organizational structures of genealogy, past the dates and towns and who begat whoms, you find small truths that touch your heart, or hidden stories that teach you the character of a person, or even a time.

You see your ancestors’ births and deaths fit into eras, and those eras fit into historical circumstances, and historical circumstances fit into your deepening thoughts about our world.

Lately I’ve been thinking about the children. In 17th, 18th and 19th century America even the most protected of them lived in a world of upheaval. A world of uncertainty and impermanence. I have some ancestors who were married two, three, and four times; not because they kept finding fatal flaws in their partners, but because their spouses kept dying. Dying and leaving both spouse and children behind. In those rougher eras, nearly a quarter of all children lost at least one parent before the age of five.

In 17th, 18th and 19th century America even the most protected of them lived in a world of upheaval. A world of uncertainty and impermanence. I have some ancestors who were married two, three, and four times; not because they kept finding fatal flaws in their partners, but because their spouses kept dying. Dying and leaving both spouse and children behind. In those rougher eras, nearly a quarter of all children lost at least one parent before the age of five.

It was just as common, more common in fact, to lose a child. Up till 1900, twenty percent of children died before they reached five. My mother’s mother lost two babies. My father’s mother also lost two babies. After researching a number of my family lines back a half dozen or more generations, I stopped naming the early deaths entirely. If the child did not live to adulthood, he did not make it onto my tree. If a spouse didn’t contribute to my blood line, I didn’t list them. That even goes for my mother’s two lost siblings, and my father’s two sisters who died before he was born, a week apart.

Priscilla was six and Elizabeth was six months. Because the gravediggers were on strike, my grandfather dug the graves himself. My grandmother expressed sorrow for the rest of her life. I have the girls’ photos, and they are beautiful babies, clearly adored and pampered by their parents. My sister displays Priscilla’s photo on her vanity dresser. I have the baby’s silver drinking cup inscribed, “Priscilla.”

Priscilla was six and Elizabeth was six months. Because the gravediggers were on strike, my grandfather dug the graves himself. My grandmother expressed sorrow for the rest of her life. I have the girls’ photos, and they are beautiful babies, clearly adored and pampered by their parents. My sister displays Priscilla’s photo on her vanity dresser. I have the baby’s silver drinking cup inscribed, “Priscilla.”

But their names are not on my family tree. I had to draw the line at children who made it to adulthood, and who grew the tree. The fruit that fell before maturing had to be left off. I don’t have room for everyone. I don’t feel good about leaving them off. I would like to honor the unfortunate babes with their rightful place in the family history, but a blessing of peace has to suffice in place of a leaf on my already overpopulated tree.

I am not the only one. In some families, the only record of a lost infant is a gap in the succession of children’s birth dates. There is no other sign; no birth certificate, no death certificate, no photo or marker. In 17th century America a normal family lost at least one child. The parents themselves were gone early, the mother at 39, her husband at 48.

What did all this death and loss and attachment and then replacement do to the children who remained? If I am unsettled because I cannot honor those lost early as members of the family tree, how could those who remained living even bear the morning sun?

Did the children learn to live with nonattachment, considering one adult guardian as good as another? Did they consider blood siblings as just another child like any other that came and went in their lives? Did they grow up to love less than we do today? Or did they grow up to love more, because they learned that strangers can come together to be a family?

Did the children learn to live with nonattachment, considering one adult guardian as good as another? Did they consider blood siblings as just another child like any other that came and went in their lives? Did they grow up to love less than we do today? Or did they grow up to love more, because they learned that strangers can come together to be a family?

Because family structure up until the 1900s was wildly different from what we think of as a normal family today. In earlier centuries, families were elastic. They took in orphans. They took in the elderly and the destitute. Even poorer families might expand the dinner table with servants and apprentices. Families grew and shrank as needs and circumstances changed. Grandparents died, and were moved onto the table in the parlor, where family gathered and paid their respects.

Parents died, and life went on. Children died, and parents mourned, but they acknowledged the cycle of birth and life and death. How could they not? The cycle of life was condensed. It swirled faster, and was often made mean by war or disease. Children were not the central concern of these families. Survival was.

Parents died, and life went on. Children died, and parents mourned, but they acknowledged the cycle of birth and life and death. How could they not? The cycle of life was condensed. It swirled faster, and was often made mean by war or disease. Children were not the central concern of these families. Survival was.

If a parent died and left his or her spouse with too many children to care for alone, the surviving parent often parceled the children out to family, friends, and even orphanages. A poor widowed mother might give her child to another family to raise in exchange for some compensation, like money, or a cow. When the mother became more settled she could try to buy back her child.

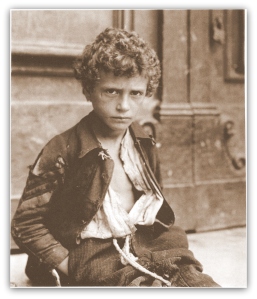

In 1620, London dealt with their street children by rounding them up and sending them to the Colonies as indentured servants. They were made to work for their masters for years to buy their freedom. More than half the English immigrants to the Southern colonies were indentured servants. Their average age was 15, and some were as young as six. A six year old servant might be nine or ten by the end of her indenture. What then? Who took in that child? Many of them, like the boy above, photographed in 1888 by Alfred Stigleitz, spent their entire childhood in the workhouse, living the meanest of lives.

In 1620, London dealt with their street children by rounding them up and sending them to the Colonies as indentured servants. They were made to work for their masters for years to buy their freedom. More than half the English immigrants to the Southern colonies were indentured servants. Their average age was 15, and some were as young as six. A six year old servant might be nine or ten by the end of her indenture. What then? Who took in that child? Many of them, like the boy above, photographed in 1888 by Alfred Stigleitz, spent their entire childhood in the workhouse, living the meanest of lives.

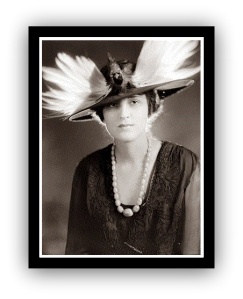

When my mother in law’s mother, shown below, died in childbirth in about 1920, she left her grocer husband with nine children that he couldn’t both care for and work. Six went to family members, but three had to be put to the orphanage until their father found and married a new mother for them. The children never did take to the stepmother, nor she to them. They found solace, refuge, and support from each other. That closeness lasted the rest of their lives. Loss is not everpresent for us today as it was just 114 years ago. Spouses are fairly assured to live till old age. Children are fairly assured to outlive their parents. You can be reasonably sure that when your wife or husband goes out for food they will not be mauled by a bear. War will not decimate your neighborhood. Your child will not die of small pox.

Loss is not everpresent for us today as it was just 114 years ago. Spouses are fairly assured to live till old age. Children are fairly assured to outlive their parents. You can be reasonably sure that when your wife or husband goes out for food they will not be mauled by a bear. War will not decimate your neighborhood. Your child will not die of small pox.

As we lose less, do we love more? Do we feel more secure in giving our love? I think the answer is yes. We are less guarded, less numb from loss already, less likely to withhold love from feeling the terrible, core-shattering pain of loss of a previous love.

If this is true, perhaps as life becomes more secure, as medicine and technology better control life’s hazards, will we as a culture love more? It’s a nice thought. Teach your children well.

When we last saw my distant ancestor John Fitch he had just buried his gold and silver on Charles Garrison’s farm in the dead of night.

When we last saw my distant ancestor John Fitch he had just buried his gold and silver on Charles Garrison’s farm in the dead of night.