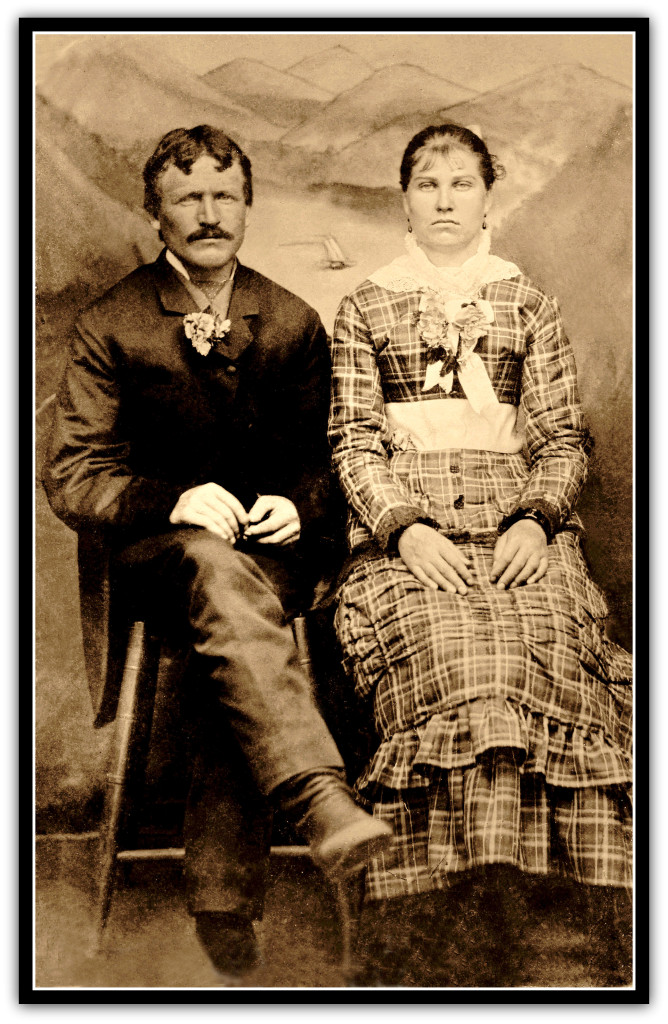

On a cool, late autumn day in 1930, or maybe 1931, Ruthy Merica and a small swarm of her grade school friends from the Fleeburg section of Shenandoah, Virginia, walked home from school as they always did, down the dirt road from their two-room schoolhouse, children dropping from the swarm here and there as they reached their front doors till it was just Ruthy, her brother Jesse, and her friend Helen. When they reached the Merica house, Ruthy invariably waved goodbye to Helen and ran around back to the kitchen door to find her mother.

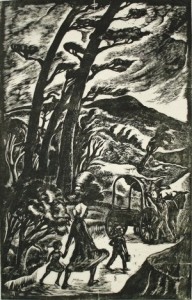

But today was different. As the swarm made its way down the road one of the children spotted smoke coming from the woods.  They all looked, and at the edge of the meadow they saw a gypsy camp, strange people with long dark hair and colorful clothes, mostly rags, lounging and milling about.

They all looked, and at the edge of the meadow they saw a gypsy camp, strange people with long dark hair and colorful clothes, mostly rags, lounging and milling about.

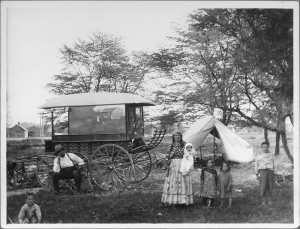

The children knew about Gypsies. They camped in the woods every autumn, then again in spring, migrating like birds south to escape the harsh northern winters and then back north in spring to some nesting grounds somewhere.

“Lock your children away, the Gypsies are near,” the children yelled, then ran ahead with shrill screams, arms outstretched and hearts thumping, racing in what they thought was a dangerous game to reach home before the Gypsies caught them.

By that night the news had spread. “The Gypsies are here,” people whispered to each other. Ruthy’s parents, Tom and Florence Merica, turned off all the lights, and kept them off so that  gypsy marauders who sneaked by night would not see their house.

gypsy marauders who sneaked by night would not see their house.

They kept the windows open all night too, so the family could listen for the chickens squawking, a sure sign something or someone was skulking about the property. They had been hit in years previous, a chicken from the coop, a ham from the smokehouse, vegetables from the garden, and they did not want to repeat those unnerving incidents.

It was different during the light of day. That’s when the gypsy women went door to door, selling expertly made baskets they wove from willows cut down by the streams. Ruthy’s mother bought one once. It was pretty, and she used it to carry vegetables from the garden.

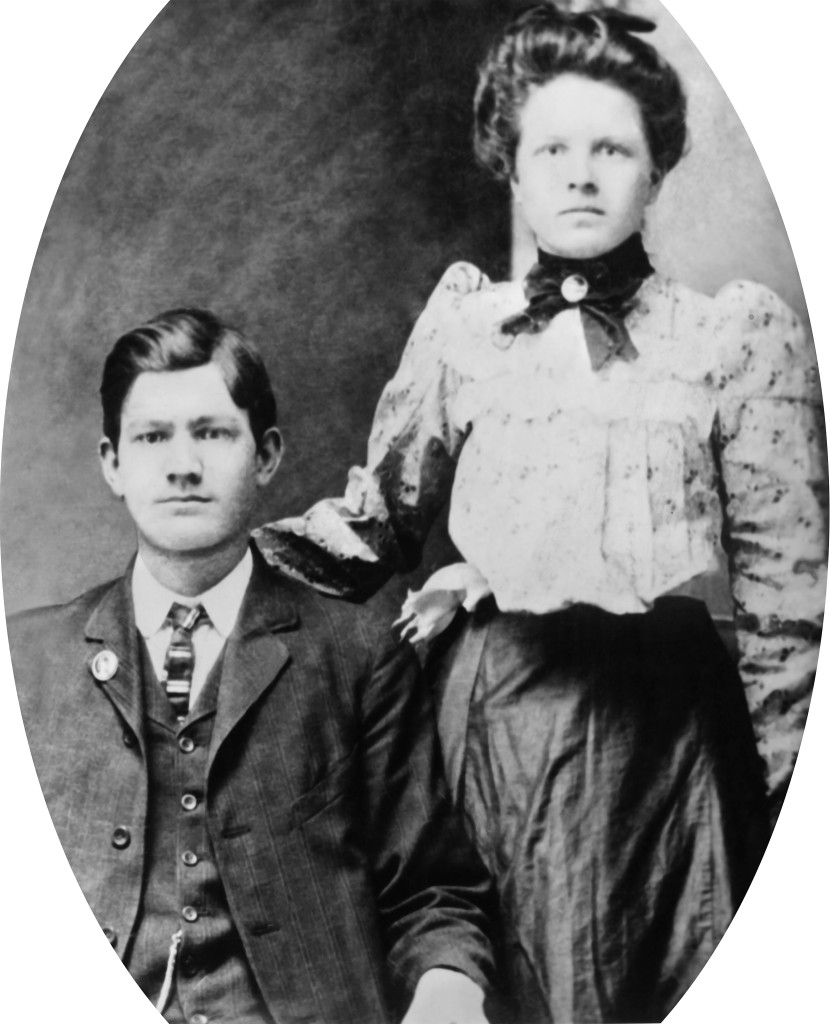

The next day Ruthy’s older sister, Ola, drove her Model A Ford to Harrisonburg to shop. Ruthy went along, as Ola liked the company and Ruthy enjoyed seeing the shops in the larger town. That afternoon on the way back, after turning from Naked Creek Road onto Fleeburg Road, Ola pulled off to the side and stopped near the Gypsy camp. She turned to Ruthy and said, “I’m going to get my fortune read.”

Ola was 13 years older than Ruthy and was married already to Raymond Grimsley, but she didn’t want her parents to think her reckless. “Don’t tell Ma or Pa,” she said, and jumped out.

Ola was 13 years older than Ruthy and was married already to Raymond Grimsley, but she didn’t want her parents to think her reckless. “Don’t tell Ma or Pa,” she said, and jumped out.

She strode through the meadow, tall and confident, more so maybe even than Ruthy’s older brothers. Ruthy got out too, but went only to the middle of the road, where she stood to wait for Ola to return. She saw Ola enter the camp, then disappear behind a tent with a woman who must have been the fortune teller.

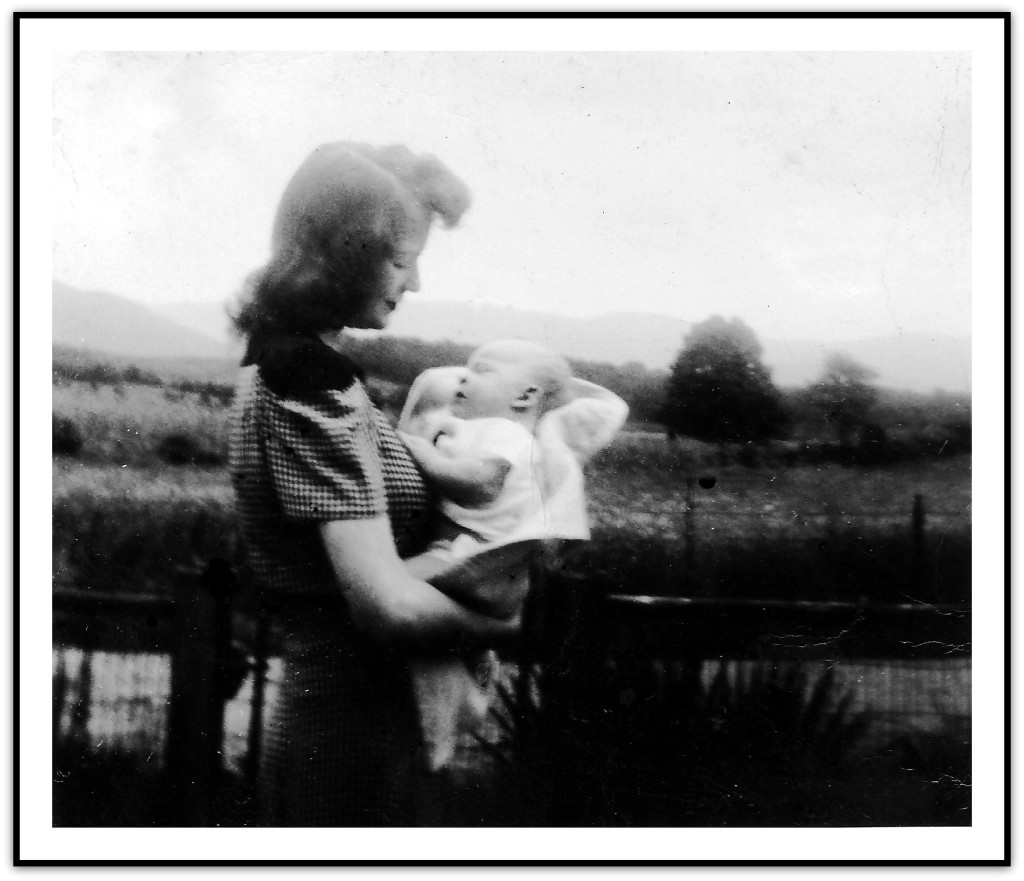

A few minutes later Ola returned across the meadow. She and Ruthy got in the car and drove the rest of the way home, where Ola dropped her off, picked up her baby, Ray, and drove back to her own home in Shenandoah. Ola never told Ruthy what the fortune teller said, and Ruthy never thought to ask her.

Seventy or so years later, I had my own Gypsy encounter. Six or seven years ago my husband and I visited Rome. I had been before, and knew exactly where in the city and its surroundings I wanted to take him.

O ur hotel suite had a beautiful view of the Roman Coliseum on one side, and around the corner on the other was the spectacular Basilica di Santa Maria Maggiore. We decided to start our day there.

ur hotel suite had a beautiful view of the Roman Coliseum on one side, and around the corner on the other was the spectacular Basilica di Santa Maria Maggiore. We decided to start our day there.

After touring this, the largest church in Rome, we were ready to eat, and so walked down the church’s massive stone steps and across the plaza to an osteria we had noticed before.

The plaza was crowded with tourists, even though we like to travel in off months to escape the crowds, say when it is rainy or cold, or both, as it was that day. Before we reached the osteria two mothers and their children approached us. The women both carried babies, and a half dozen children surrounded them. The mothers caught and held our eyes, pleading for money to feed their children, and then the children mobbed us, their hands out and cupped, pulling on our clothing and talking all at once in some language I did not recognize. We were sympathetic, but the scene was getting out of hand. We kept moving, but they bound themselves around us inescapably.

Their sudden appearance startled us, erasing any spiritual calm we absorbed while inside the church, and as these moments were just short of frightening, we frantically made our way to the osteria. Just before we reached it, they fell away and disappeared. All this happened over only a few seconds.

Once inside the quiet osteria we regained our calm over a relaxed lunch, planning where to go next. When we were ready to leave, Patrick, my husband, reached for his wallet. It was gone, as was his passport, his credit cards, and about $1,000 in cash, which we stupidly had not put in a safety deposit box that morning.

I immediately jumped up and ran outside to find the two mothers, or a policeman.  Scanning the street, I spied one of Italy’s tiny police cars rounding the church, and flagged it down. What ensued was a mad-cap ride through the streets of Rome in the back of a police car, with countless other police cars joining the chase, each going a different way. It was comical in a Buster Keaton, Keystone Cops way.

Scanning the street, I spied one of Italy’s tiny police cars rounding the church, and flagged it down. What ensued was a mad-cap ride through the streets of Rome in the back of a police car, with countless other police cars joining the chase, each going a different way. It was comical in a Buster Keaton, Keystone Cops way.

Long story short, we found the culprits, and they were arrested. The Roman authorities asked us politely if we would go to court the next day to testify. It seems that there was a terrible crime wave against tourists in Rome, and they needed our help to convict these perpetrators. Most tourists, they said, will not agree to testify, because they don’t want to lose precious and limited tourist time in the courthouse. We, on the other hand, thought this sounded like a wonderfully unique adventure, practically worth the cost of our losses, and so agreed.

I’m skipping many of the interesting details, but the upshot of our adventure was that once in court the prosecutor said the thieves were Gypsies, members of a huge group of refugees from war-torn Bosnia who came here with nothing and so turned to thieving to feed their families.

Once we found out more about these maligned people we felt compassion for their lifetime of misfortune. We decided we did not want to press charges, but by that time it was too late. The state had taken control. We didn’t even have to testify for those two women to be convicted, and for their children to be put in homes, though family members would be able to extract the children. The sentence was one year. We felt horrible. My husband kept track of the sentence, and on the anniversary of their release we hoped and prayed for their better lives.

Once we found out more about these maligned people we felt compassion for their lifetime of misfortune. We decided we did not want to press charges, but by that time it was too late. The state had taken control. We didn’t even have to testify for those two women to be convicted, and for their children to be put in homes, though family members would be able to extract the children. The sentence was one year. We felt horrible. My husband kept track of the sentence, and on the anniversary of their release we hoped and prayed for their better lives.

The Gypsies are mysterious, and their origins just add to the mystery. We know they were originally from India, and their language even today, for any left who speak it, is based on Sanskrit. But we don’t know why they left India in the 10th century, migrating through Persia and arriving in Europe roughly 800 years later, where they were given the name Gypsy, because Europeans of the Middle Ages thought they were from Egypt.

They came to America originally in the 17th and 18th centuries, banned as they were from England, France, Portugal and Spain. More arrived from Serbia, Russia, and Austria-Hungary after the 1880s.

They came to America originally in the 17th and 18th centuries, banned as they were from England, France, Portugal and Spain. More arrived from Serbia, Russia, and Austria-Hungary after the 1880s.

Today there are between 100,000 (National Geographic) and one million (Wikipedia, PBS) Gypsies living in the United States, mostly in Los Angeles and Chicago, and about 12 million worldwide.

Governments around the world have always tried to ban the Gypsy’s way of life. They said, “You cannot live in wagons pulled by horses and travel in caravans.” Later they said, “You cannot live in vans and travel from place to place. You must have a house, and send your children to school.”

It is no better for the Roma (the Gypsy name for themselves) today. Right now, the anti-Roma sentiment is only growing. Hundreds of thousands of Roma fled the war-torn Baltic states into Western Europe. Now France and Italy burn their camps and deport them. In Romania their homes are bulldozed, even though the Roma may have lived in them for decades. The EU put travel restrictions on Romania and Bulgaria, hoping the stem the tide of Roma emigrants.

A backlash against the hatred is growing. Pope Francis spoke out against Roma discrimination. He said, “I remember many times here in Rome when some Gypsies would get on the bus, the driver would say: ‘Watch your wallets!’ This is contempt. It might be true, but it is contempt.”

Will the Gypsy culture survive? It has already lost much, and now, not since Hitler has there been such dedication to eradicating that way of life, if not those people themselves.

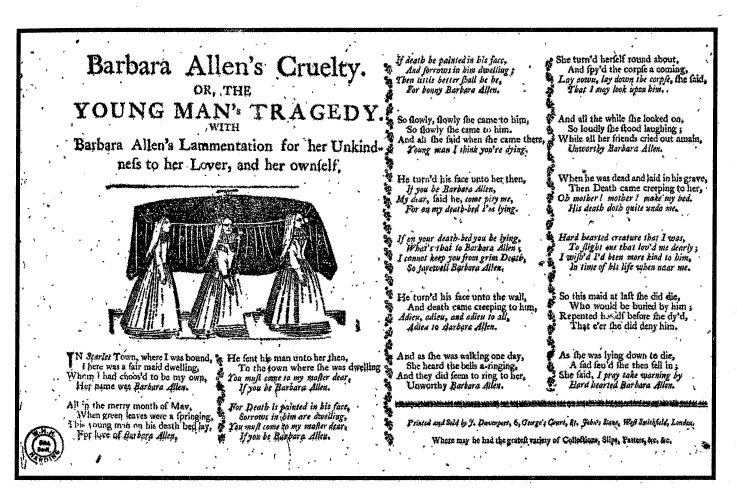

A revered Gypsy poet called Papusza wrote,

The time of the wandering Gypsies

Has long passed.

But I see them,

They are bright,

Strong and clear like water.

You can hear it

Wandering when it wishes to speak.

But poor thing, it has no speech

Apart from silver splashing and sighing.

Only the horse, grazing in the grass,

Listens and understands that sighing.

The water does not look behind.

It flees, runs farther away,

Where eyes will not see her,

The water that wanders.

Ruthy, my mother, knew instinctively that the gypsies didn’t steal children, but our reactions to superstitions are not triggered by our rational minds.The mysterious “other” has always engendered fear.

Ruthy, my mother, knew instinctively that the gypsies didn’t steal children, but our reactions to superstitions are not triggered by our rational minds.The mysterious “other” has always engendered fear.

Yes, my family’s only two encounters with Gypsies involved theft, and a culture of theft is intolerable. But with so many fears bestowed upon the Gypsies, do they even have a chance to live better lives? The world denies them their nomadic life, denies them the tradition of oral rather then written knowledge, says their children must attend school.

They have clung to their ways through centuries of the worst persecution. But can they survive this latest attempt at forced integration?  The Gypsy’s ways have always been misaligned with the cultures around them.

The Gypsy’s ways have always been misaligned with the cultures around them.

Perhaps that’s why they first took to the road. And maybe that’s why they stay on the road even today, because wherever they stop, they are eventually asked to leave. No wonder they are nomadic.

in the 1700s: Francis Meadows and his wife, Mary; and Martin Crawford and his wife, Elizabeth McDonald.

in the 1700s: Francis Meadows and his wife, Mary; and Martin Crawford and his wife, Elizabeth McDonald. McDaniel, and David Turner and Catherine Lucas.

McDaniel, and David Turner and Catherine Lucas.

left Brooklyn.

left Brooklyn. you heard me tell the story and then remembered it as though it was your own.”

you heard me tell the story and then remembered it as though it was your own.”

So some descendants have taken action, working with the Park to ensure that our ancestors’ histories are told to Park visitors, and told in the right light; building memorials outside the Park, maintaining Park-land cemeteries.

So some descendants have taken action, working with the Park to ensure that our ancestors’ histories are told to Park visitors, and told in the right light; building memorials outside the Park, maintaining Park-land cemeteries.

ancestors, and we can almost see ourselves right there beside them, conversing in their ancient language, living between our time and theirs.

ancestors, and we can almost see ourselves right there beside them, conversing in their ancient language, living between our time and theirs. bulldozed to make way for urban cities, the old people moved carelessly to apartment dwelling or some other unfamiliar government convenience.

bulldozed to make way for urban cities, the old people moved carelessly to apartment dwelling or some other unfamiliar government convenience.

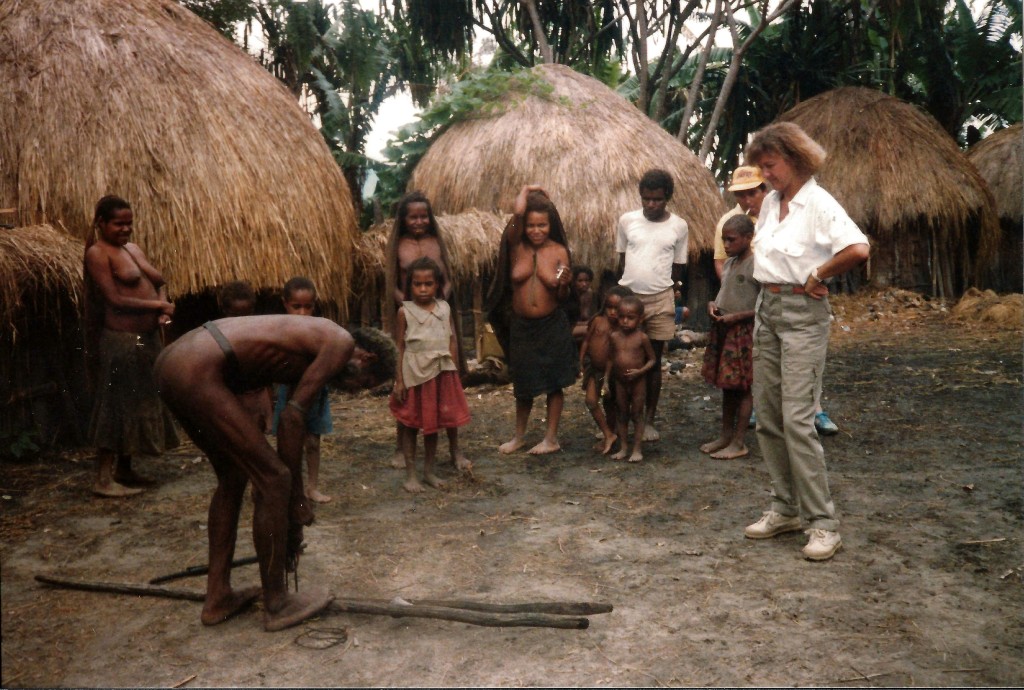

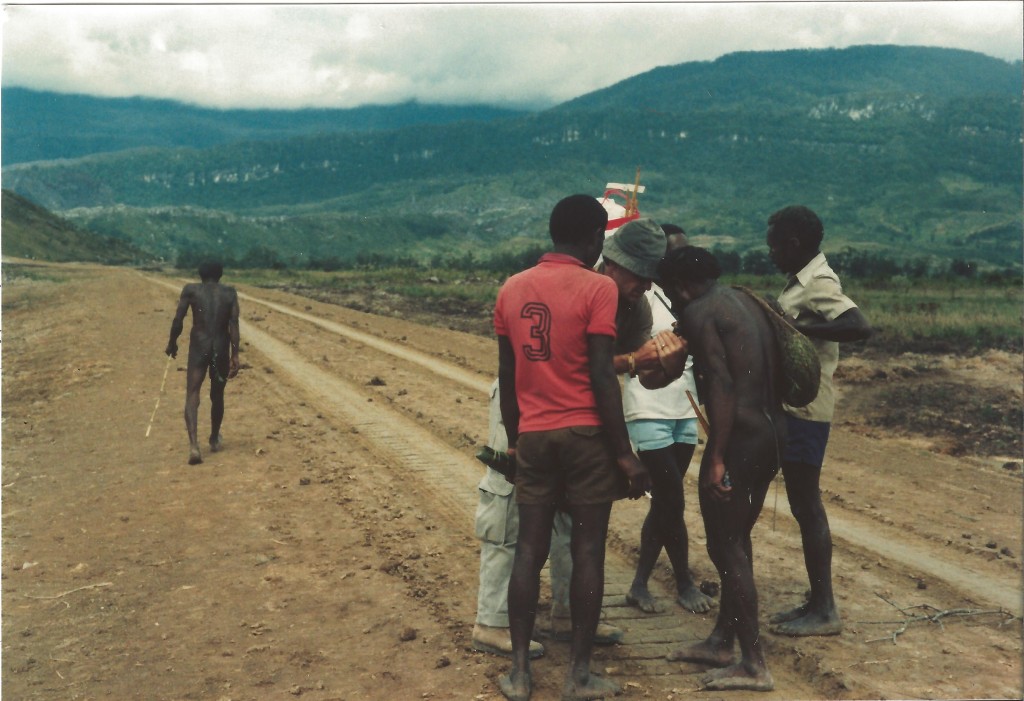

Michael Rockefeller, of “those” Rockefellers, was part of that team until he disappeared, his body never to be found.

Michael Rockefeller, of “those” Rockefellers, was part of that team until he disappeared, his body never to be found.

a distant island, decided to build a road over the mountains and into the Baliem Valley, where the primitive Dani lived.

a distant island, decided to build a road over the mountains and into the Baliem Valley, where the primitive Dani lived. nslaught of popular culture? No. I can say that unequivocally. It may not be tomorrow, or next year, or in ten years, but it will happen.

nslaught of popular culture? No. I can say that unequivocally. It may not be tomorrow, or next year, or in ten years, but it will happen.

sprung from between their fallen walls, and 80 seasons of fallen leaves have covered their remnants.

sprung from between their fallen walls, and 80 seasons of fallen leaves have covered their remnants.

But for the tenants, I’m not so sure. I lived many years in rentals before buying a home. Renters have few rights, no matter where you are. That’s simply the way it is, dehumanizing as it may be.

But for the tenants, I’m not so sure. I lived many years in rentals before buying a home. Renters have few rights, no matter where you are. That’s simply the way it is, dehumanizing as it may be.

I imagine their very first reaction was negative though, on hearing that the government was condemning their property and evicting them from their homes. Who would be happy about that? But time, and the offer of money, which was in short supply for most of these people, won in the end.

I imagine their very first reaction was negative though, on hearing that the government was condemning their property and evicting them from their homes. Who would be happy about that? But time, and the offer of money, which was in short supply for most of these people, won in the end.

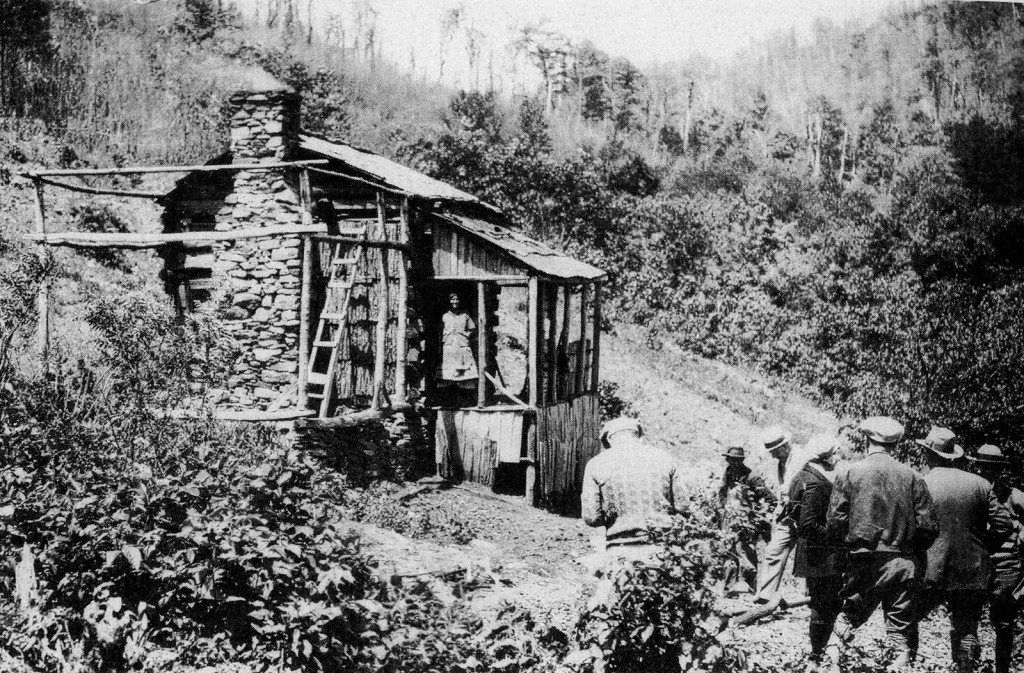

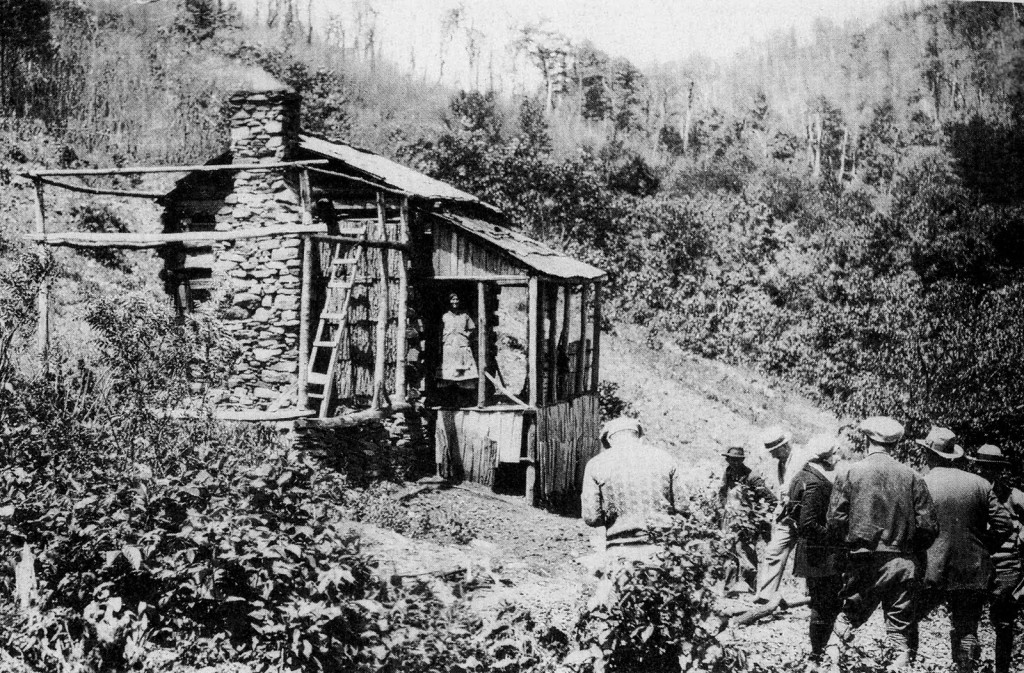

These were families who had been there for generations. Many lived in compounds of extended families, with parents, brothers, grandparents all with their own small homes. Some were so poor that they couldn’t afford to move anywhere else. Each family’s circumstance was different, but I guess that every one of them was a complex tangle of emotions, needs, desires, and problems that had to be dealt with before they could pull up roots and leave.

These were families who had been there for generations. Many lived in compounds of extended families, with parents, brothers, grandparents all with their own small homes. Some were so poor that they couldn’t afford to move anywhere else. Each family’s circumstance was different, but I guess that every one of them was a complex tangle of emotions, needs, desires, and problems that had to be dealt with before they could pull up roots and leave.

lies and buried their old, and often their young too, in cemeteries just a few steps away. Midwives delivered babies, herbalists consulted on medicine, and occasionally, the fortune teller up in the woods near Waynesboro read nervous young women’s futures.

lies and buried their old, and often their young too, in cemeteries just a few steps away. Midwives delivered babies, herbalists consulted on medicine, and occasionally, the fortune teller up in the woods near Waynesboro read nervous young women’s futures.