My mother had her own drawer as a child.

With a family of 12 in a four-bedroom farmhouse that’s all she could get, one drawer.

12 in a four-bedroom farmhouse that’s all she could get, one drawer.

But she didn’t feel deprived, she felt special.

The way she put it was, “My mother gave me my own drawer.”

She doesn’t know if her brothers or sisters had their own drawers, because, “I just thought about my drawer, not theirs.”

It was the Depression, and theirs was one of the fortunate families. They had their farm, and Mom’s father had a good job with the Norfolk & Western Railroad.

They had abundant food and some income to buy new shoes and little combs, maybe a doll at Christmas, and to go to the fair once a year and get other occasional small luxuries that gladden a child’s heart.

In the afternoons after school, with her homework done and still too early for supper, she liked to open her drawer and look at her special things.

There was a small, doll-sized tea set, and sometimes she had te a parties for her doll on the downstairs parlor windowsill.

a parties for her doll on the downstairs parlor windowsill.

There was a doll’s comb, and sometimes she sat on the edge of her bed and quietly combed the pretty hair on her precious doll with the bisque head.

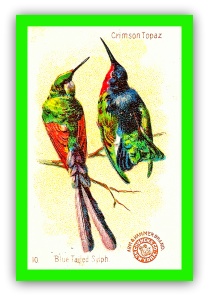

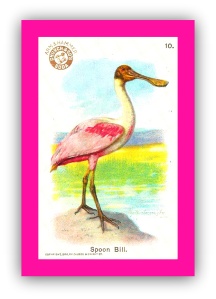

But what she loved best of all were her bird cards. She had a whole stack of them and she liked to take them out, spread them on her bed, and look at them.

But what she loved best of all were her bird cards. She had a whole stack of them and she liked to take them out, spread them on her bed, and look at them.

She examined each of the birds, their colors, the fineness of their feathers, the tilt of their heads, the way they perched so lightly on a twig.

Then she turned the cards over and read what they said on the other side.

She read about the brown thrasher, that, “On beautiful May mornings he is seen and heard singing his clear, rollicking, joyous, and variable song, while perched on the topmost branches of tree or bush.”  Such vibrant, lyrical language!

Such vibrant, lyrical language!

She read that the dickcissel’s “unmusical song, which is given with great earnestness, resembles the syllables, ‘dick dick chee chee chee chee,’ and from this the bird’s name is derived.”

And that the crested flycatcher’s territory “is pugnaciously guarded by the male, who brooks no intrusion by any other bird.”

But mostly she looked at the delightful pictures. Each of them was drawn with great skill in vivid colors and detail exacting enough to show the bird’s features, but artistically enough to be a creative representation of the bird in its environment.

She handled them gently, always carefully restacking them and putting them back into the drawer, precisely in the near-right corner, squared to the two drawer sides.

Her mother gave them to her, only her, and she got a new card every time her mother came home from the store with a new box of Arm & Hammer baking soda. They came one to a box.

Her mother gave them to her, only her, and she got a new card every time her mother came home from the store with a new box of Arm & Hammer baking soda. They came one to a box.

Sometimes after looking at her bird cards she liked to go to the windowsill of her upstairs bedroom and watch for the real kind.

Her home was at the edge of land where the rolling green valley of Shenandoah meets the dense forest of the Blue Ridge Mountains.

She could look out past he r mother’s locust tree, west across the long sloped field where Stony Run Creek flows from Grindstone Mountain, and beyond that to far distance where Bearfence Mountain sits at the peak of the Blue Ridge Mountain range.

r mother’s locust tree, west across the long sloped field where Stony Run Creek flows from Grindstone Mountain, and beyond that to far distance where Bearfence Mountain sits at the peak of the Blue Ridge Mountain range.

I don’t know if she knew how privileged she was to grow up in one of the most beautiful places in the world.

But she did recognize and treasure the beauty and everything that environment gave her.

Off in the field she could see vivid blue buntings perched precipitously on swaying twigs.

And grosbeaks with their bright red chests. Towhees were harder to see, blending  with the field grass and bushes until they flew from their hiding place.

with the field grass and bushes until they flew from their hiding place.

Pretty bluebirds sometimes nested in the locust, and in summer the robins always seemed to be hop-hop-hopping along.

Sometimes she tried to catch them. “If you put salt on its tail,” her mother told her, “you can catch it.”

She tried sneaking up close. She tried tossing salt from as far as she could throw.

She tried dropping it on them from up in the peach tree, where she sat quietly until one got near enough.

But nothing worked. She only realized years later that what her mother meant was that if she could sneak close enough to shake a sprinkling of salt on the bird’s tail, she was close enough to grab it.

No matter. The bird cards were just as amazing as the birds themselves.

They were painted by Louis Agassiz Fuertes, considered by some as history’s greatest portraitist of birds.

He did 90 paintings for Arm & Hammer’s chromolithographed bird cards. Today the originals are among the collections of Cornell University.

Today the originals are among the collections of Cornell University.

Some say the cards were so popular that they helped create the Victorian era bird watching phenomenon, when dapper men and dainty ladies alike took to hill and vale to catch a prized view of rare and colorful birds.

Arm & Hammer added mottoes to the cards: “For the good of all, do not destroy the birds.”

It was already too late for the passenger pigeon.

What had been a bird so plentiful that flocks would darken the sky, became  extinct when Martha, the last one, died on September 1, 1914.

extinct when Martha, the last one, died on September 1, 1914.

Now conservationists were afraid for other birds as well.

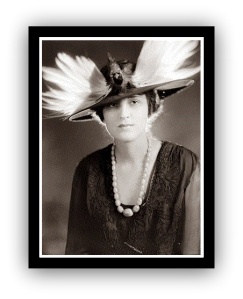

The birdwatching craze included watching for bird feathers on ladies’ hats, the more glori ously spectacular the plumes, the better.

ously spectacular the plumes, the better.

Some hats even sported entire stuffed birds. More than 95 percent of Florida’s shore birds were killed by plume hunters.

Two women objected. They started a group they called the Audubon Society, and waged a nationwide campaign to stop the feathers for fashion craze.

Thanks to them, and to conservationist president Theodore Roosevelt, an act of Congress was passed to stop the slaughter.

them, and to conservationist president Theodore Roosevelt, an act of Congress was passed to stop the slaughter.

My mother was spared knowing any of that. She just loved her birds. And her bird cards.

I don’t know when she stacked the m in the near-right corner of her drawer for the last time.

m in the near-right corner of her drawer for the last time.

They were still in there when she placed her high school diploma in the drawer.

And when she went off to Washington D.C. to work as a shop girl at Garfinkle’s department store.

The drawer became someone else’s, and the cards disappeared sometime over the years.

But my mother never lost he r love of birds, and today, at age 93, she sits in the patio and watches yellow finches cover the finch feeding bags.

r love of birds, and today, at age 93, she sits in the patio and watches yellow finches cover the finch feeding bags.

When her children call, she always tells them how her birds are doing, and whether the mallards have visited the swimming pool.

She doesn’t have any bird cards, but she remembers them, the favorite of all the special things she kept in the drawer that was her own.