First names, like eye color, tend to run in families.

In my (ex) brother-in-law’s family, every first son is James, every second son is John. It has been like that for generations. He broke the tradition by a hair, naming his first son John. James will have to wait for esteemed son number two.

My sister tossed on our own family naming tradition by adding a middle name for baby John that is old-fashioned and multi-syllabic: Chauncey, which is the name of our great-great grandfather.

Chauncey is also a name that is typical for my family. Given names for us tend to be a mouthful: Theodore. Cynthia. Thaddeus. Justine. Florence. Priscilla. Abigail. Frances.

In all 2,101 ancestors I’ve come up with so far, our most common female name is Mary. There are 112 of them, which still leaves 1,989 who are not named Mary. That makes for a lot of unique names.

Of course, each generation seeks its own naming trends,whether we’re talking the 1980s or the 1480s.

Every one of my 16 Abigails are from the 16- and 1700s, except one 1800s.

Sometimes these generational naming trends fight family traditions for naming supremacy.

And so somewhere right now 2014’s trending “Joshua” is bumping a favorite family name off the birth certificate. Just as the name “Ashley” did a few years ago.

And the way “Ruth” spiked from 66th to fifth most popular girl’s name after the birth of the hauntingly beautiful “Baby Ruth,” daughter of President Grover Cleveland, in 1891.

But does every family have names as odd as mine?

Look through my ancestors and you’ll find Aleonore, Amabil, Ansfred, Apollonia, Apollos, Augustine, and Avelina. And Benoni, Beriah, Biggett, Bishop, and Bran. That doesn’t even exhaust odd names from the A’s and B’s!

Of course, they probably weren’t odd for the time, and that’s where it helps to put on your best Sherlock Holmes deerstalker hat and play Ancestral Name Detective.

Of course, they probably weren’t odd for the time, and that’s where it helps to put on your best Sherlock Holmes deerstalker hat and play Ancestral Name Detective.

You can sometimes guess in what era an ancestor was born, or the circumstances of an ancestor’s birth, just by the their name.

My eighth great grandfather was Benoni Gardiner. That odd name is a clue that his mother might have died in childbirth, which she probably did, as her year of death is also his birth year.

It didn’t take me much Googling to find that Benoni is a name that had special meaning in early New England families. It comes from a passage in Genesis on the death of Rachel, wife of Jacob:

And it came to pass, as her soul was in departing, (for she died) that she called his name Benoni: but his father called him Benjamin.

It’s no trick at all to know that my ancestors, Silence Brown, Delight Kent, Mindwell Osborne, Temperance Stewart, and Thankful Clapp were all named in the trendy Puritan practice of choosing virtues as children’s names.

It’s no trick at all to know that my ancestors, Silence Brown, Delight Kent, Mindwell Osborne, Temperance Stewart, and Thankful Clapp were all named in the trendy Puritan practice of choosing virtues as children’s names.

And with a name like Henry de Pomeroy, you can bet my 21st great grandfather lived in 11th or 12th century England, which he did.

But I admit I was thrown by my 18th great grandmother, Ethel May Dyer, who was born in 1320 England, not the early 20th century American Midwest.

You can learn a lot about history, too, when researching ancestral names.

Walter Giffard, my 23th great grandfather, was born in 1040 in Normandy. I figured he must have palled around with William the Conqueror, because next we see him he’s been installed as Earl of Buckingham after William won the Battle of Hastings in 1066 and parked his throne in England.

Sure enough, a little Googling proved my hunch was right. (Don’t be too impressed. The Battle of Hastings in 1066 is one of the few historical dates I remember from school.)

At first ol’ Norman-named Walter was surrounded by people with weird Anglo-Saxon names like Cyneweard, and his friends Godric, Aelfwine, Godgivu , Aethelred, and Deorwine.

William and his Norman crowd brought their refined, wine-drinking names with them, and the not-so-sore-losing conquerees soon discovered that they liked both the culture and the names of the conquorers better.

That’s why your neighbors are probably William instead of Wigberht, John instead of Eoforhild, or Susan instead of Swidhun.

It’s also the reason there are, statistically, 60 Michaels to every Hector, and 57 Johns to every Stuart.

Because the pool of popular children’s names shrank after the Norman invasion.

Instead of the Anglo-Saxon baby name book that would have been hundreds of pages long, parents would have had more of a pamphlet to go through now.

To put it another way, if you went out to meet a group of ten friends in England in about 1300, the group would have, statistically, two Johns, two Matildas, at least one William and Isabella, and either a Thomas, Bartholomew, Cecilia, or Catherine for the others.

Naming became so uncreative in England, in fact, that there were sometimes several children with the same names in one family.

Like a family noted in the History of Parish Registers, which reads:

Like a family noted in the History of Parish Registers, which reads:

“One John Barker had three sons named John Barker, and two daughters named Margaret Barker.”

I just hope they didn’t all look alike too.

It got confusing real fast. Thus the surname became a thing.

For a while, last names kept to the knitting. If you read King Edward IV’s accounting books from 1480, you would see IOUs made out to:

John Poyntmaker, for pointing of xl. Dozen points of silk pointed with agelettes of laton.

To a laborer called Rychard Gardyner working in the gardyne.

To Alice Shapster for making and washing xxiiii. Sherts, and xxiiii. Stomachers.

But they started running into a problem of duplicates, so someone got smart and extended the roster of names by adding “son” (in whatever appropriate language) to the ends of given names.

Then someone else started in on adjectives, like Short, Little, Red, or White.

Then someone else started in on adjectives, like Short, Little, Red, or White.

Then they started putting their creative muscle into it and got Longfellow, Blackbeard, Stern, and Peacock (“vanity, vanity, all is vanity”).

You probably don’t know anyone named “Crooked Nose,” but maybe you know a Cameron, which is Gaelic for the same.

And you probably don’t know an “Ugly Head,” but I bet you know its Gaelic version, Kennedy.

You probably do know what the name Williamson means. But I bet you didn’t know that William is German for Desire Helmet.

It’s fun to play ancestral name detective, though it can be frustrating. But if you’re hitting brick walls that you need to find a way around, put on your deerstalker hat and think like Sherlock. You might be surprised at how well it works.

The list is a 58-page searchable pdf with many hundreds of names.

The list is a 58-page searchable pdf with many hundreds of names.

You don’t know why that happened, and so decide the skies must be angry.

You don’t know why that happened, and so decide the skies must be angry. Or that the seasons are determined by the sun’s position relative to earth. The sun, we know, grows weaker in the winter and stronger in the summer for those of us in the northern hemisphere because of the tilt of the earth’s axis.

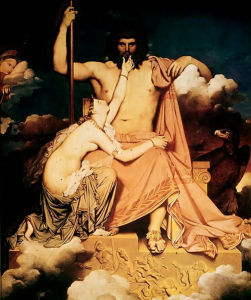

Or that the seasons are determined by the sun’s position relative to earth. The sun, we know, grows weaker in the winter and stronger in the summer for those of us in the northern hemisphere because of the tilt of the earth’s axis. The Germanic Goddess Gefjun plowed the land and brought abundance and prosperity. Apollo, god of sun and light, drew his chariot across the sky by a team of celestial horses, driving the sun in its course.

The Germanic Goddess Gefjun plowed the land and brought abundance and prosperity. Apollo, god of sun and light, drew his chariot across the sky by a team of celestial horses, driving the sun in its course.