In 1834, Richard Henry Dana sailed south from Boston around Cape Horn and up the long Pacific coast to California. Upon seeing the vast emptiness of our coastal land he wrote in his diary, “What brought us into such a place, we could not conceive.” No trees, “not even a shrub,” in fact nothing “except the stalks of the mustard plant.” A “desolate looking place,” he wrote.

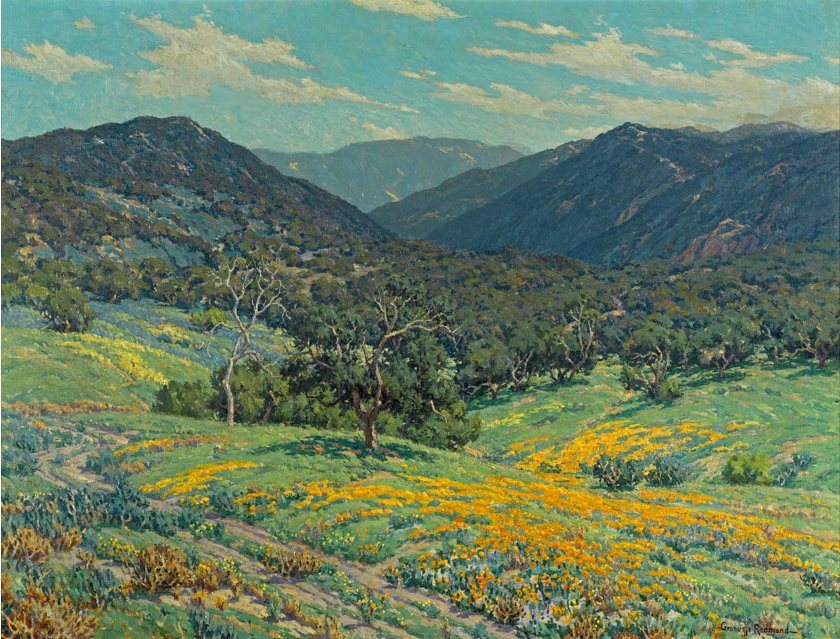

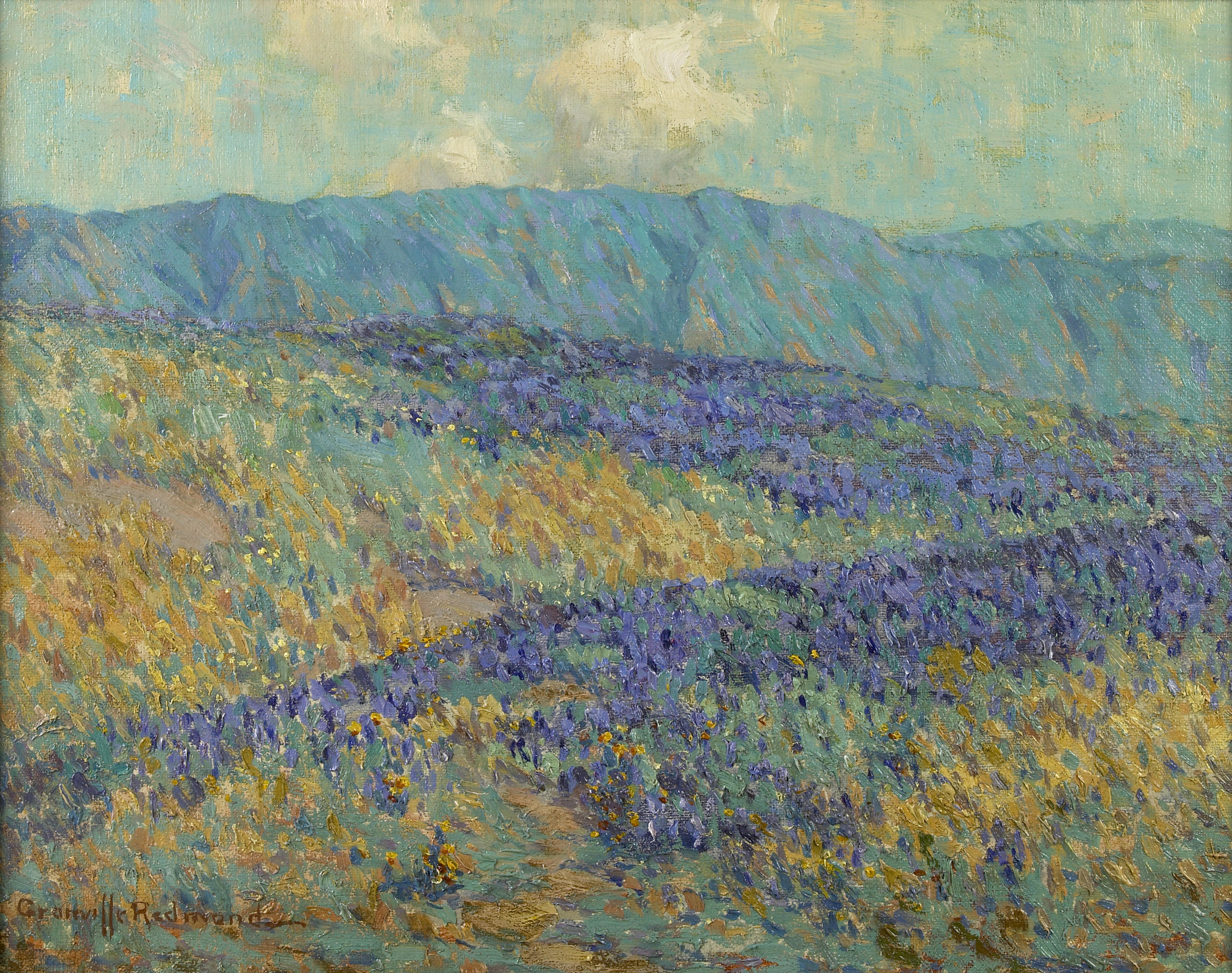

Perhaps the long months at sea had cowled his vision. When I look on our landscape in spring, I see hills and fields dappled in hues of green from deep moss to light-catching chartreuse, a many-colored coat that quivers under the infinite and achingly blue sky. It is

our coastal sage scrub, alive and kicking, its deep roots siphoning spring’s water to quench its thirst and pack away against summer drought, turning leaves these vivid hues and nourishing nascent buds that will soon burst into bright bloom. Velvet-leafed California sage, feathery buckwheat, puffy deerweed, tall toyon, spiky goldenbush, ghostly white sage, ashy purple sage, and dozens of others create this rich palette.

These are accented by open fields that wear a dazzling sheath of brightest yellow, Dana’s wild mustard, brought here, legend has it, as seeds lodged in the hooves of cattle, or scattered by Spaniards along the trail called El Camino Real to help them keep the path. In spring the blooming mustard cascades down hillsides, stretches over fields, undulates in rippling waves under the breeze. Look closely and you can see meadowlarks swaying at the ends of willowy stems, heads thrown back to call out their complex and melodic song, or blackbirds flashing a blaze of red wing as they flit from stalk to stalk. Splashes of blue

lupine and golden poppy are the dazzling jewels that trick out Mother Nature’s outfit. And if you’re lucky, you chance upon an elfin patch of delicate shooting stars, faces down, stamens thrust forward, and pale lavender petals streaming back like the tail of a comet. Above, billowing clouds, white as fields of cotton, cast patched shadows that pass over the vivid landscape like a whispered secret, then blow away. How can you call such a place dull?

I had a friend once who came here from New York. She said, “To love California you have to love brown.” I can understand the scornful judgment she must have felt after living in a place where trees and shrubs and vines and grasses grow in lush abundance. California can seem barren after such extravagance. My view, though, is that to love California, you must be unafraid of the vastness here. Job said, “Speak to the earth, and it will teach you.” Whether we learn is up to us. Standing at the edge of the ocean, the portal to the stars, the door to the far horizon, how small we are and how boundless is nature. Some people climb

to the tops of mountains to behold the majestic view. Here, especially before suburbia spread its pervasive tentacles, we need only to top the nearest small rise to see into the far distance, past the green velvety hills. The first time I drove across Florida, I was near panic for the claustrophobia I felt. The roads are straight and flat, and trees crowd to the very edge of the asphalt. You can’t get your perspective. You can’t place where you are in the landscape. You are hemmed in, flying blind. I could hardly wait to reach home, where I could once more see to the curvature of the earth.

After being on the southern California coast for a few months, Dana did begrudgingly admit that “there was a grandeur in everything around,” with hills that “ran off into the interior as far as the eye could reach.” He added, though, that “the only thing which diminishes its beauty is, that the hills have no large trees upon them.” He believed he was “at the ends of the earth; on a coast almost solitary; in a country where there is neither law nor gospel.” Let him and his kind go home then! It only means fewer people and more wide open spaces for us.

From the time that Dana visited California until the 1950’s, more than 100 years later, not much had changed. Towns had sprung up along the coast, but past that thin strip of humanity, the hills and valleys remained essentially as empty as they were in the earliest times. Emptier, in fact, after extermination of the Native Americans who were wiped out by the Spanish. But that is a different chapter.

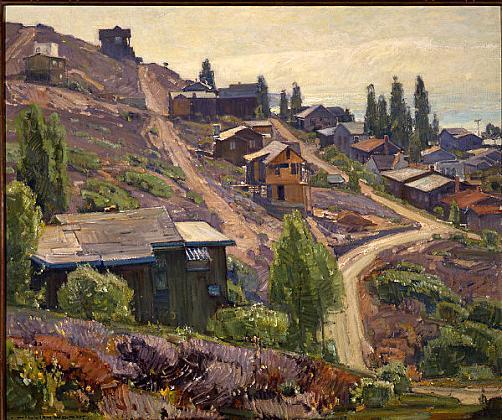

By the mid-1950’s, Coastal North San Diego County had sprouted a series of pleasant villages strung along the sandstone bluffs that rise like sentinels above the Pacific Ocean. The towns were not old by most standards, but already well-worn by the sun and salt air. At a distance they all looked alike, hanging onto the bleached coastal hillsides like memories of lost love, sweetly faded with time. Up close, they still looked alike, little houses and little shops, beige as sand, square as boxes, unadorned by the gables and porticos and acreage that marked wealthier communities like Rancho Santa Fe. Languid under the gauzy haze of summer mornings, calm as churches, the sleepy villages were as if a dreamland that existed separate from the rest of the world. No hustle or bustle disturbed the peace of those places. For most, to live here was a choice made for the sake of beauty. Beauty and ease. Beautiful sparkling ocean, whose rhythmic swells sighed like the breath of Neptune; beautiful golden hills billowing to the distant horizon; beautiful sunny, warm skies that made living easy. In those years this was paradise, a secret kept by its inhabitants, who were here by a wholly gratuitous grace.

There are philosophers who have spent entire lifetimes arguing whether beauty exists outside of human experience or rests only in our eyes. St. Augustine, history’s great confessor, asked “What is it that allures us and delights us in the things that we love? Unless there was grace and beauty in them they could not possibly draw us to them.” He opted on the side of objective beauty. I don’t know if beauty exists outside our experience of it, but I do know that our little Elysium by the sea was made so by the wonder and reverence which was inspired in those of us who lived here.

One of the smallest villages along the coast was Cardiff-by-the-Sea, where tacky bungalows were anchored like barnacles to the bumpy hillside streets, some of them still unpaved 40 years after the town’s founding. Weed-filled empty lots stood as reminders that no one was rushing to build in this remote outpost nearly an hour from the nearest city, where there were no industries to draw skilled workers or resorts to seduce luxury tourists. We lived by

a different kind of ambition, one that cherished the hedonism of simplicity over material wealth, and self-direction over prestige. Nearly everyone made their livings in support of the community – keeping shop, educating children, building or repairing houses, tending health, keeping peace – and so were in service to each other, engaged in the good of all.

A comforting harmony lay over the town like a soft blanket. The local newspaper, the Coast Dispatch, carried front-page stories about Little League games, or someone finding a litter of lost kittens. Kids dug pits in the dirt of empty lots and tunneled dens in the thick lemonade berry bushes, dividing into factions to launch harmless attacks on each other. Teens built giant bonfires on the beach on warm summer nights, dancing to the music of the stars. Parents sent their children to the Cub Scouts, Brownies, Blue Birds, Little League, and 4-H. I’m sure that inside their homes there was as much drama and disease as anywhere else, but the spirit of the place was a soothing balm upon the bruises of life.

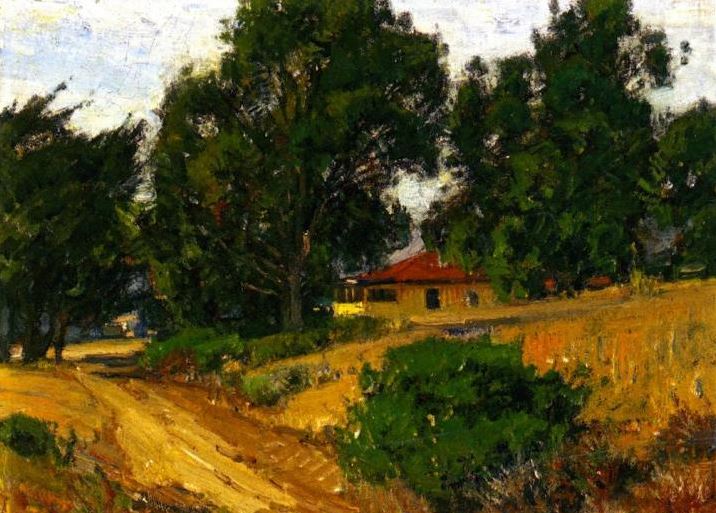

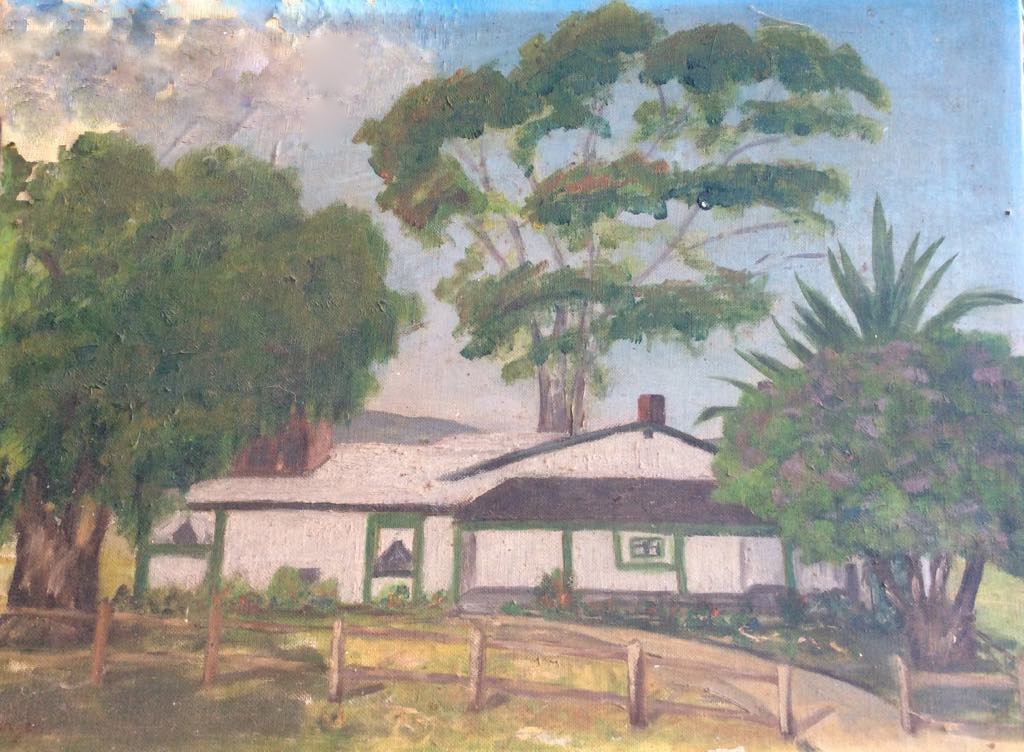

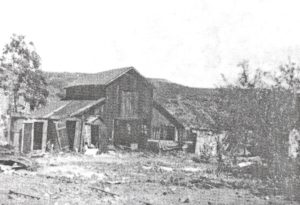

My own family came here after rejecting the institutions of the East. My grandfather, ex-scholar, ex-Wall Street interpreter, ex-inventor. My grandmother, ex-lady, whose preference had always been to live in New York City. They brought my father, ex-Air Force by way of World War II; my mother, dark-eyed country girl; and my father’s brother, ex-Manhattan musician. They brought few skills that were easily transferrable to this frontier, though, and so decided they would build houses. My grandfather, still the scholar, went to the library in San Diego and discovered the ancient art of adobe, and so that is what they did: they built adobe houses, learning their trade from an encyclopedia. They made adobe bricks on-site from the ubiquitous clay soil and straw, stacking them one on another until a house emerged, the way a painting emerges from the dashed strokes of an artist. They

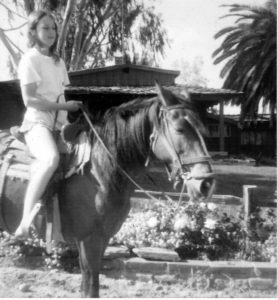

bought an old ranch with a dilapidated house that was unfit for my mother, young brothers, and grandmother, who stayed at the Sturdivant apartments on the bluff next to the Self Realization Fellowship in Encinitas while my father and grandfather made the ranch house habitable (this was before I was born). My grandmother and uncle never did live there, preferring to live in town. We all spent lazy Sundays together.

Cardiff was the closest town to our ranch, just over the hill that separated us from the ocean. There was no road up the hill, which meant we had to drive three miles around it to reach Cardiff, skirting the edge of the placid San Elijo Lagoon that swept up the coastal plain from the shore like a shimmering scarf. The lagoon bustled with a busy community of seabirds. The snowy egret, standing still as a held breath, stately as a lord, until raising his head plume in showy display, like a mad composer. Fulgent mallards whose luminous

feathers seem to change from green to blue to purple as they catch different angles of the light. Rare California least terns, whose black caps enshroud their eyes like an executioner’s mask, darting and plunging for the small fish they feast on. Busy stilts, funny backwards-kneed yellow legs bending and stretching, bending and stretching, as they patrol the shallow water in search of juicy snails or insects. Watchful hawks, soaring high overhead on the currents of the wind until they sight some prey below. Then they fold their wings into their bomb-shaped bodies and drop into a death dive that sends rabbits and squirrels scurrying for cover. Voluptuous white pelicans that dip and turn in synchronicity, beaks up, beaks down, a shimmering chorus line to match anything on Broadway. And of course, the mud hen, the most blundering bird, all thumbs, who lands on his head as often as on his belly, the way ducks ought to. In spring the swallows arrived to build their mud nests into the sandstone cliffs, and in later years, onto the San Elijo overpass of Interstate 5. They came in vast colonies, and crowds of them flittered in hectic flight all summer over the estuary, feeding on whatever insect dared to brave such dangerous airspace. Years later the avian community was joined by a trio of gay flamingos that arrived mysteriously from unknown parts. The San Diego Zoo claimed they weren’t missing any of the stilted pink oddities, yet no one could think of any other way they could have gotten there.

In heavy rains, water drained off the many hills that stretched along Escondido Creek and fed into the lagoon, swelling its volume until it spilled over, obliterating any sign of the road that ran along its edge, our only link to town. My father drove then by faith alone, knowing from having traveled that route for years where the asphalt should be beneath the water. Like the skipper of some awkward motorboat he navigated through water that

San Elijo Lagoon in flood, from Cardiff-by-the-Sea, by Wehtahnah Tucker and Gus Bujkovsky, courtesy Doug White

sometimes reached above the chassis, scattering dumbfounded mud hens before us, a wake veeing out behind us. Less daring drivers didn’t brave those high seas, and instead turned back to the long drive through Rancho Santa Fe and down to Del Mar to reach the coast highway to Cardiff, a 10-mile detour. In later years engineers would raise the road, but in those days, into the early 1970’s, driving San Elijo Road could be treacherous. For reasons I don’t understand, fog was denser back then, too. When it lay particularly heavy over the lagoon, one of my brothers would get out and walk the unmarked road so my father could find his way behind without tumbling the car into the water below.

Cardiff proper began at the northwest side of the lagoon, where the remains of a kelp factory from before World War I could still be seen on a steep bluff above the ocean, its dark bulkhead bent and broken like Jeremiah weeping for his own demise. At the estuary’s outlet to the sea, the bones of old pilings protruded from the surf where a pier once ran 300 feet into the Pacific. Once there was a perpetual motion machine at the end of the pier, designed to harness energy from the waves, but a storm wiped out the machine and the pier in 1915, just a year after they were erected. Wind energy would have to wait nearly another century before becoming viable.

The Cullen Building was the center of town, an imposing two-story former hotel that now held the small country grocery store where we did most of our shopping, the Cardiff Mercantile. As in other small towns where everyone knew each other, customers took what they wanted on credit and paid at the beginning of each month, a form of trust that has been all but exterminated today, replaced by the anonymity of leech-like credit card companies. Cardiff also had a library, barber, grammar school, dentist, doctor, and post office. Town dwellers had their mail delivered, but we lived too far out, and so had a post office box, which I still remember: Route 2, Box 2605-A.

The school held a festival once each year called the Native Fair, an event put on in the parking lot and featuring games, prizes, a bake sale, and talent competition. One year a friend recruited me to sing a duet for the contest. We practiced “Oh What a Beautiful Morning” after school at her house for weeks, and on the day of the event stood before the small and polite audience and did our native best to squeak out the tune, which was written for voices far better than ours. We didn’t win, and the experience taught me that I had no talent as a singer and no stomach for performing.

Like other small towns along the coast, Cardiff was built abreast of the railroad tracks and Highway 101, both of which ran from San Diego to the Canadian border. Once there was a railway station, but after a few years they realized that nothing much happened in this place. Few people got on or off here, and the few who did could as easily go to the Encinitas station a mile and a half to the north. Nor was there much reason to pull off the highway to visit Cardiff’s town center. There was a Richfield gas station at the corner of Chesterfield and San Elijo, built in 1920. At Christmastime they handed out pretty pamphlets of Christmas songs, and my sister and I sang them all season in the back seat as my father drove.

But the only restaurants and souvenir store were down along a strip of highway at the beach south of town, where there was a seashell shop, Elmer’s Rocket gas station, the Sea Barn café, Evan’s motel, George’s restaurant, and the rowdy Beacon Inn Hotel, where a mostly out-of-town clientele went for the 3 D’s – dining, drinking, and dancing. Cardiff’s teens liked to hang out at the South Cardiff Lodge, which was converted from Elmer’s gas station. As an adolescent, I used to go to the Sea Barn with my father, who was good friends with the owners, whose names I have long forgotten. Sometimes I picked a basket of mulberries and they would bake us a pie while we ate lunch, then bring out two warm and steaming slices topped with a scoop of vanilla ice cream.

And then there was the beach, that irresistible boundary between land and sea, a coexisting of opposites, a place for physical and emotional regeneration, and shelter against the anxieties of civilization. We go to the beach because it soothes our souls. It calms our anxieties. We enter the water and are born again, like sinners who are given a second chance to feel the presence of the Divine. We let the waves wash away our gloom, or loneliness, or discouragement. We lie in the sand and let the sun purify us, baking out weariness, reviving our spirits and our potency. We walk the tideline and feel the dual power of land and sea charge our blood and bones with energy.

It wasn’t always so. In ancient times, the ocean was feared, portrayed in the Bible as a remnant of primordial creation, chaotic and dangerous, outside the Garden of Eden, and inhabited by the terrible monster, Leviathan. Vikings built their ships with fierce heads and open jaws at bow and stern, there to ward off evil spirits. Renaissance artists characterized the sea as raging, incomprehensible, ready to suck in those who ventured too close, as into some liquid hell.

Not until the 18th Century was the seashore seen in a more positive light, when the Romantics reinvented the ocean as a symbol of eternity, and the beach as a place for leisure, health, and socializing. William Wordsworth wrote, “The gentleness of heaven is on the sea,” and people went out to take a look. Cautiously they ventured out to picnic on the beach, take in the invigorating salt air, even dip beyond the tideline into the sprawling surf. And they never looked back. Now the idea of the seashore has been completely rehabilitated. We flock to the coast both to play and to live, crowding each other into smaller and smaller spaces for the sake of proximity to the sea. Forty percent of the US population lives on the coastline. By 2020 another 10 million people will shoehorn their way in, which begs the question, at what point does suffocating density cancel out the received grace of living by the sea?

Richard Henry Dana would be shocked to see how many people choose to live on this coastline, at this “desolate-looking place.” Some of us are here because we refuse to give up on it, despite the invading hoards that have descended upon us since the boomtimes of the 1970’s. We think ourselves special, pioneers of a place that was once paradise. We look askance at the newcomers, anyone who has been here fewer than 50 years. But time’s march is inevitable, and we are helpless to the changes it wroughts. My brother escaped to the mountains. My sister left for even farther mountains. And me? I don’t know if I’m cut out for life inland. I once lived in Chicago for several seasons. When it was time to return here my husband and I decided to drive cross-country instead of fly. I swear to you that when we reached the top of the Rocky Mountains and passed over the Continental Divide, I could smell the familiar scent of salt air. I was coming home.

I don’t live in Cardiff anymore. I grew up believing that it was necessary to leave home, to have a career. Cardiff was too small a place for my wide eyes. Even now, I can’t go back; I am not that forgiving. But I am still on the coast, and in the spring I can still find fields of brilliant yellow. I can still gaze far to the distant mountains. And I can still dip my feet into the healing waters of the Pacific and be regenerated. Thomas Wolfe reminded us that we can’t go home again. Yet for me, the little ranch on the outskirts of Cardiff where I grew up will forever be the truest home I have ever known.

October is peak tourist season in Shenandoah National Park, when the forest puts on a dazzling show that never fails to delight.

October is peak tourist season in Shenandoah National Park, when the forest puts on a dazzling show that never fails to delight. For 200 years those generations eked out their living from the rough soil and rugged mountains.

For 200 years those generations eked out their living from the rough soil and rugged mountains.

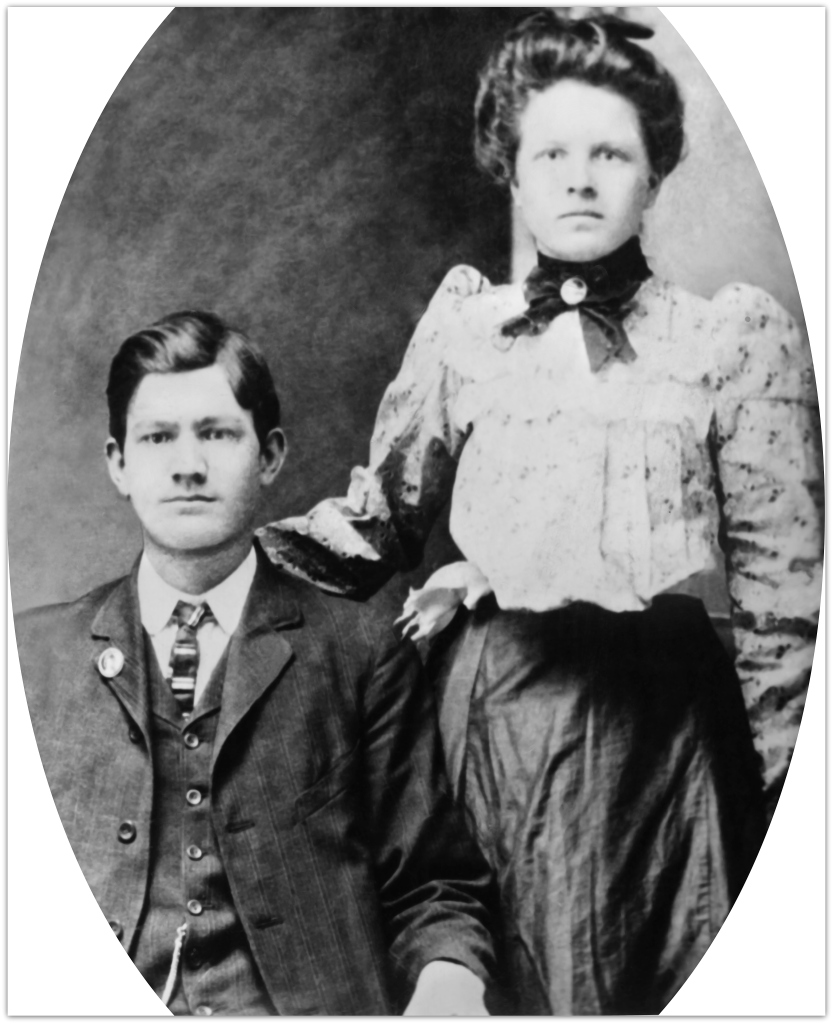

among those summarily tossed out. William Durret Collier and his wife, Mary Meadows Collier, lived up the mountain from Jollett Hollow.

among those summarily tossed out. William Durret Collier and his wife, Mary Meadows Collier, lived up the mountain from Jollett Hollow.

but all through the cities and countryside looking for pockets of poverty to eradicate.

but all through the cities and countryside looking for pockets of poverty to eradicate.

Did others make out financially as well? Looking at the evidence, I have to say it seems most did.

Did others make out financially as well? Looking at the evidence, I have to say it seems most did.

t was no doubt at one of the area’s frequent barn dances that she met her future husband, Thomas Austin Merica. She was 17 when they married, and so small around that her young husband, tall and strong, could put his hands around her waist, making her blush with secret delight. That delight never left, and even years later her cheeks flushed when her husband spoke affectionately to her, especially when he called her Sally, a pet name.

t was no doubt at one of the area’s frequent barn dances that she met her future husband, Thomas Austin Merica. She was 17 when they married, and so small around that her young husband, tall and strong, could put his hands around her waist, making her blush with secret delight. That delight never left, and even years later her cheeks flushed when her husband spoke affectionately to her, especially when he called her Sally, a pet name. wisps falling about her neck and ears. The story goes that her thick chestnut hair fell below her waist until a bout with pneumonia thinned it.

wisps falling about her neck and ears. The story goes that her thick chestnut hair fell below her waist until a bout with pneumonia thinned it.

radio, and lived a just and satisfying life, relatively free of drama or pain.

radio, and lived a just and satisfying life, relatively free of drama or pain.

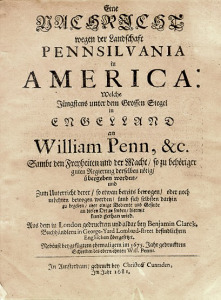

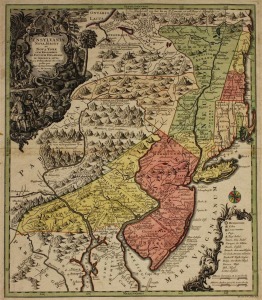

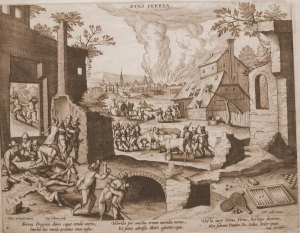

To emigrate in the Seventeenth or Eighteenth Century was to leap by faith alone into the unknown, leaving behind home and family, familiar neighborhoods, routines well established, even loved ones they never wished to leave behind. All to begin again from scratch with little more than a few precious dollars and enormous stores of energy and faith.

To emigrate in the Seventeenth or Eighteenth Century was to leap by faith alone into the unknown, leaving behind home and family, familiar neighborhoods, routines well established, even loved ones they never wished to leave behind. All to begin again from scratch with little more than a few precious dollars and enormous stores of energy and faith. they drive emigrants to leave their homes and venture into the unknown. We’ll never know their particular kind of hope and fear mixed with regret and relief, the concoction of emotions that has driven immigrants to our land for nearly four hundred years, and continues to drive them today.

they drive emigrants to leave their homes and venture into the unknown. We’ll never know their particular kind of hope and fear mixed with regret and relief, the concoction of emotions that has driven immigrants to our land for nearly four hundred years, and continues to drive them today.

the countryside and its people were in ruin. Religious hatred and political divisions pitted Catholic against Protestant, Hapsburg against Ottoman, north against south, prince against prince, and in their armies, peasant and farmer against peasant and farmer. The devastation was enormous, the taxes oppressive as local leaders sought more and more money to wage war.

the countryside and its people were in ruin. Religious hatred and political divisions pitted Catholic against Protestant, Hapsburg against Ottoman, north against south, prince against prince, and in their armies, peasant and farmer against peasant and farmer. The devastation was enormous, the taxes oppressive as local leaders sought more and more money to wage war.