Annie Ada Collier Harris loved her husband dearly. He was a farmer, and she went to the fields each day just to be near him. She took him his lunch, sat with him, watched him eat, and the two of them talked.

I never saw them do this. I never met my Great Aunt Annie or her husband, Grover Lee Harris. But my mother, who is 93 now, and who is Annie’s niece, tells me these things. “She was deeply in love with her husband,” Mom tells me.

Before he got old Grover went blind. He could no longer work, or go to the fields. Annie read to him. And he sat with her while she tatted her lace. Her fingers moved quickly, and every few stitches she ran the needle that someone had made for her through her hair, and that oil helped the needle glide through the threads.

Her hands were never idle, and her home and the homes of her family members were never without lace. Lace doilies for the tables, lace antimacassars for the backs and arms of chairs, lace trim on the sheets and pillowcases, on sleeves and collars. Her sisters laughed about it, but loved her lacy gifts.

Annie and Grover were married for 39 years before he died. Annie buried him near their #2 Furnace home, at the Koontz Cemetery at Naked Creek.

Their children, Wilma (Wilmy) and Agnes were grown and married by that time. Wilmy married Clarence Blose and Agnes married Joseph Merica. Joseph was the grandson of George Strother Merica, who was the grandson of Johannes Merkey. Johannes was also my third great grandfather from the line of Mericas that reaches down through my grandfather, Thomas Austin Merica, who was married to Aunt Annie’s sister, Florence.

That’s just the way it works in the Blue Ridge.

After Grover died, Aunt Annie was alone for the first time in her life. Sure, she had her daughters, but she had been deeply in love with Grover, as my mother keeps telling me, and missed him terribly.

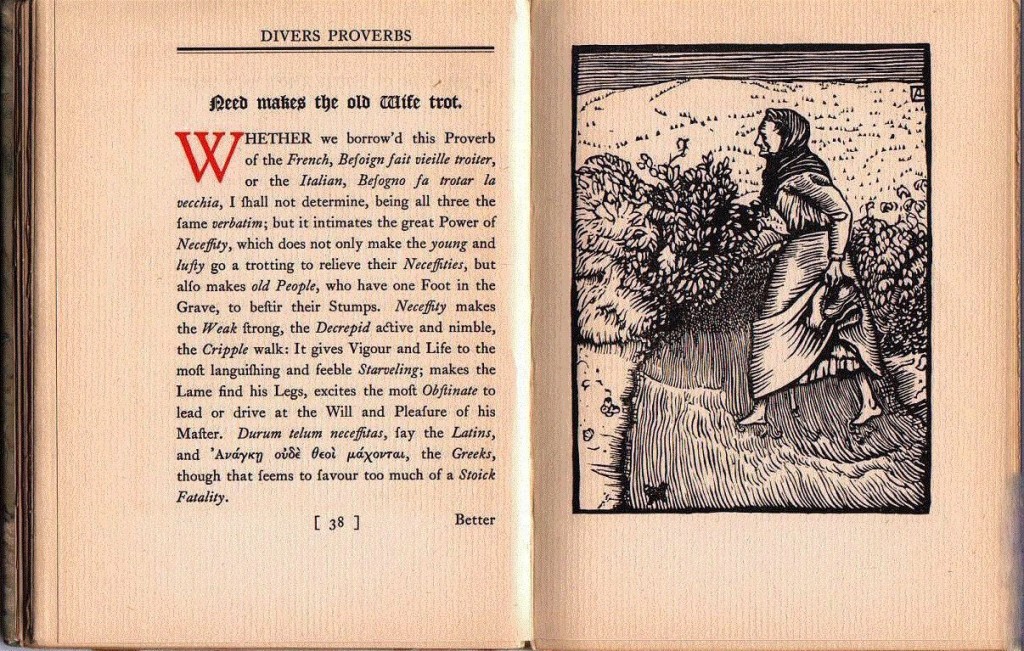

There’s an English proverb, Need makes the old woman trot. The 1917 Dictionary of Proverbs explains,

“it intimates the great Power of Necessity, which does not only make the young and lusty go a trotting to relieve their necessities, but also makes old People, who have one Foot in the Grave, to bestir their Stumps. Necessity makes the Weak strong, the Decrepid active and nimble, the Cripple walk: It gives Vigour and Life to the most languishing and feeble Starveling, makes the Lame find his Legs, excites the most Obstinate to lead or drive at the Will and Pleasure of his Master.”

Aunt Annie had a need, and that was to be with people after Grover was gone. And so she took to visiting. She visited her sister Florence, my grandmother, for days or weeks at a time. They were both widows and enjoyed each others’ company. That’s what widows did. Used to the hustle and bustle and needs of busy households during their earlier years, the walls of their now-empty houses crept in on them if they did not get out for happy, long visits. Always to family.

Aunt Annie had a need, and that was to be with people after Grover was gone. And so she took to visiting. She visited her sister Florence, my grandmother, for days or weeks at a time. They were both widows and enjoyed each others’ company. That’s what widows did. Used to the hustle and bustle and needs of busy households during their earlier years, the walls of their now-empty houses crept in on them if they did not get out for happy, long visits. Always to family.

Aunt Annie and my grandmother used their time together to make quilts. Their favorites were crazy quilts, those Jackson Pollocky riots of colored bits of stitched-together cloth. They chattered and gossiped and quilted their days away, never hurrying, never impatient to be somewhere else or doing something else.

Annie visited her daughters, and I imagine that she visited her other sister and her brother. She visited nieces and nephews, too, like my Uncle Jesse Merica’s family in Waynesboro. My cousins remember her visits.

She took the Trailways bus from Elkton to Waynesboro and Jesse’s wife, my Aunt Emily, picked her up at the station. Aunt Annie stepped down from the bus carrying her two paper shopping bags with handles made of twine, her thick stockings rolled to just above her knees, and wearing heavy black shoes with two-inch heels and three eyelets for the laces. Everything she brought was in those two paper bags. She didn’t need much, just the company.

When she arrived the first thing she did was to count out enough money for her bus ride home and put that back in her coin purse. The rest she had for spending, mostly on supplies for lace-making that she stocked up on before going home, although she always took out a nickel or a quarter for the children.

No matter who she was visiting, Annie kept to her routine. At night she put on her nightgown and let down her long, white hair. Then she brushed it. Many strokes, till it shined like silk, or like starlight. She took off her glasses and set them on the night table, tied a black scarf around her head so she wouldn’t get earaches, then she reverently got down on her knees to murmur her quiet prayers to God.

I don’t know what she prayed for. Maybe for the soul of her beloved husband. Maybe for the safety and happiness of her daughters. She probably prayed also for her sisters and their families. That was her world.

The next morning she pulled her hair up again into a tight bun worn at the back of her head. She put on her stockings, rolled them to her knees, tied her black shoelaces, grabbed her tatting bag, and was then ready for anything.

Annie Ada Collier Harris loved her husband so much that she visited his family after he died, my mother tells me, even though they lived over the mountain in Greene County.

Annie Ada Collier Harris loved her husband so much that she visited his family after he died, my mother tells me, even though they lived over the mountain in Greene County.

One day she was visiting my grandmother, Florence Collier Merica, and as she readied to leave she said, “I’m going to visit Grover’s family, so I’ll have a lot to tell you when I come next time.”

But before she went on her visit she needed to rest up. She went home, took off her bonnet, lay down on her bed for a nap, and never got up.

My cousins tell me Aunt Annie was “a sweet old woman.” Their stories, and my mother’s, make that clear.

grass and starving sheep. But that was just her living circumstances. She had her adored Robert, and then Priscilla. That was all she really needed, anyway.

grass and starving sheep. But that was just her living circumstances. She had her adored Robert, and then Priscilla. That was all she really needed, anyway.