I did not set out to write a multi-part series on the Blue Ridge Mountain evictions, but as the original post became longer and longer, I decided to split it into parts, all of which I will post in upcoming days. Be sure you read parts One and Two. I also want to thank Jon Bilous for the use of his exquisite Blue Ridge photos. You can see his entire Blue Ridge portfolio here.

My Blue Ridge Mountain Home Eviction: Part 3

Most Americans blow away from their family trees like fall leaves in a high wind. They drift to wherever jobs and prevailing winds take them, commence flying the local colors and rooting for their new local team, and forget any loyalties they ever had elsewhere, remembering family only as a holiday obligation.

Most Americans blow away from their family trees like fall leaves in a high wind. They drift to wherever jobs and prevailing winds take them, commence flying the local colors and rooting for their new local team, and forget any loyalties they ever had elsewhere, remembering family only as a holiday obligation.

But we’re not all like that, are we? I was born of a 10th generation Virginian, my mother’s Meador ancestors first arriving in Virginia from England in 1636. They’ve now stayed in Virginia for 378 years and counting. In fact, the family name moved more than the family did, morphing from Meador to Meadows sometime over their first two centuries here.

By 1743 the Meadows family moved from Virginia’s coastal plains at the Rappahannock to the heart of the Blue Ridge Mountains, on Hightop Mountain, near Swift Run Gap, and thus I was born not just to a 10th generation Virginian, but to a fifth generation Blue Ridgian. Indeed, seven of my mother’s eight great grandparents were from those mountains, the origins of the eighth being so far unaccounted for.

This is not unusual in the Blue Ridge. In fact, it’s typical. What is unusual is that my mother moved all the way to California. It’s unusual because most people born to the Blue Ridge don’t leave. It’s unusual because she is the only one of nine children to leave. It’s unusual because… here it comes… 94 percent of those born in Appalachia (of which the Blue Ridge is part) are descended from families that have been there since the American Revolution, five, six generations ago.

I am from California, where everyone is from somewhere else, and so to me that is an astonishing testament to the bonds that tie my mother’s family and other Blue Ridge natives to their homes and families. I should add that I am not just astonished, I am envious. My childhood home is gone, vanished, my clan disbursed like dandelion seeds in the wind to take root elsewhere. From six or more related households within a few miles of each other in Encinitas and Leucadia, California, we blew outward to Oregon, Washington, North Carolina, the High Sierras, Alaska, and elsewhere. No one is left in our little hometown. Even our home is gone, torn down to make way for something bigger.

What are these ties that bind some so firmly to family and place? Why are Blue Ridge natives (for I’m interested only in Blue Ridge natives, not Appalachians in general) so different from the rest of the country? I found a Facebook page that’s open only to those whose ancestors are from that one small area of Virginia. It’s an active site and its members are amazingly knowledgeable about their and even their neighbors’ ancestors. I’ve never seen that anywhere else. They are historians, and clearly love their work. They are also clearly proud of their ancestors. There are certain surnames that have prestige, the honor of a long history in the Blue Ridge. The Breedens, Lams, Eppards, Turners, Deans, Meadows, Hammers. And some, like the Hensleys and Shifflets, are genealogical royalty, their families spread across those mountains for centuries, like history’s icing.

What are these ties that bind some so firmly to family and place? Why are Blue Ridge natives (for I’m interested only in Blue Ridge natives, not Appalachians in general) so different from the rest of the country? I found a Facebook page that’s open only to those whose ancestors are from that one small area of Virginia. It’s an active site and its members are amazingly knowledgeable about their and even their neighbors’ ancestors. I’ve never seen that anywhere else. They are historians, and clearly love their work. They are also clearly proud of their ancestors. There are certain surnames that have prestige, the honor of a long history in the Blue Ridge. The Breedens, Lams, Eppards, Turners, Deans, Meadows, Hammers. And some, like the Hensleys and Shifflets, are genealogical royalty, their families spread across those mountains for centuries, like history’s icing.

We’ve all seen people who proudly announce their ancestors are this president, that king, some other inventor or explorer. When telling you, they have a pleased expression, as if thinking that genetic connection makes them smarter, or more important in the scheme of history. But it’s different in the Blue Ridge. When those descendents proudly point to a photo of their ancestor, you’re likely to find yourself looking at a worn-out looking man or woman dressed in old, maybe tattered clothes, maybe sitting in front of a barely-standing shack in a dirt yard.

I get that. Those are my ancestors too, at least on my mother’s side. Within this Blue Ridge genealogy group on a Facebook page, I have that same pride. The blood of these strong, determined, American pioneers runs through my veins. They climbed the mountains, hacked their homes from the wilderness, raised strong families, fended for themselves, helped their neighbors, never infringed on anyone else and asked only to never be infringed upon. Their clothes were raggedy, but yours would be too if you had just made America. While Thomas Jefferson and John Adams may have been the brains that created this country, these people were the backbone that gave America its strength and character.

I get that. Those are my ancestors too, at least on my mother’s side. Within this Blue Ridge genealogy group on a Facebook page, I have that same pride. The blood of these strong, determined, American pioneers runs through my veins. They climbed the mountains, hacked their homes from the wilderness, raised strong families, fended for themselves, helped their neighbors, never infringed on anyone else and asked only to never be infringed upon. Their clothes were raggedy, but yours would be too if you had just made America. While Thomas Jefferson and John Adams may have been the brains that created this country, these people were the backbone that gave America its strength and character.

They made their homes in the mountains of Virginia, one of the most beautiful places I’ve ever seen on the five continents I’ve traveled, and so grand a place that their descendents have stayed through half a dozen generations, staying as close to those original Blue Ridge mountain homes as they can. They’re bound to that place by some undefinable force. Way out here in California I feel it too, pulling me back to a place I’ve never lived.

When I was growing up I would sometimes say that my mother was from the South. That gross inaccuracy always rankled her, and she would correct me, “I am not from the South, I am a Virginian.” That is an important distinction, something she’s always been proud of. She is equally proud to be from Shenandoah, and if there were some sort of shorthand way of saying it so others would understand, I’m sure she would proudly tell people she is from close to where her grandparents and great grandparents and great great and great great great grandparents lived their entire lives, back to five generations ago.

Unlike the 94 percent who remain there all their lives, she didn’t want to stay. She wanted all the experiences a bigger world could give her. But she took Shenandoah and the Blue Ridge with her, and then she passed them on to me. Like I say, I have Blue Ridge in my blood. I feel richer for it. And who knows, maybe some day I will live there.

You can read Part Four of My Blue Ridge Mountain Home Eviction here. Or access the whole series here. To make sure you don’t miss any installments, go to the “subscribe” form at the top of this page.

casting long shadows from its woodlands, that endless green like a carpet of rumpled velvet, and those blue-tinged mountains beyond, brings a tear to my eye for such beauty.

casting long shadows from its woodlands, that endless green like a carpet of rumpled velvet, and those blue-tinged mountains beyond, brings a tear to my eye for such beauty.

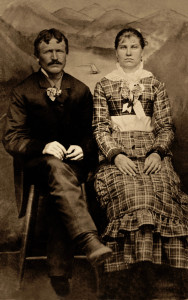

Mary Meadows, daughter of Mitchell Meadows and great great granddaughter of Francis Meadows, was born in 1864 in the Blue Ridge, just up from Jollett Hollow, which sits on the eastern edge of the great Valley of Virginia, the Shenandoah. There she grew up, and there she married William Durrett Collier, whose people also came to the mountains early.

Mary Meadows, daughter of Mitchell Meadows and great great granddaughter of Francis Meadows, was born in 1864 in the Blue Ridge, just up from Jollett Hollow, which sits on the eastern edge of the great Valley of Virginia, the Shenandoah. There she grew up, and there she married William Durrett Collier, whose people also came to the mountains early.

days like their parents and their grandparents and really, like you and me, a version of the American life, if not the American dream. They raised five girls and a boy, all hard-working but fun-loving youngsters who, my mother quotes her mother, Durrett and Mary’s youngest, as saying, “hoed corn all day and danced all night.”

days like their parents and their grandparents and really, like you and me, a version of the American life, if not the American dream. They raised five girls and a boy, all hard-working but fun-loving youngsters who, my mother quotes her mother, Durrett and Mary’s youngest, as saying, “hoed corn all day and danced all night.”

They are gentle, welcoming, not at all intimidating, as are our Sierras that separate California from the rest of the country like a knife edge.

They are gentle, welcoming, not at all intimidating, as are our Sierras that separate California from the rest of the country like a knife edge.

There is a profound silence telling you that secrets hide here, covered by mists and time and the forests that reclaim their pristine past.

There is a profound silence telling you that secrets hide here, covered by mists and time and the forests that reclaim their pristine past. Of the Blue Ridge, he wrote:

Of the Blue Ridge, he wrote: And of Shenandoahans, he wrote:

And of Shenandoahans, he wrote: I couldn’t agree more.

I couldn’t agree more.

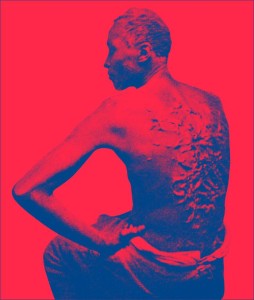

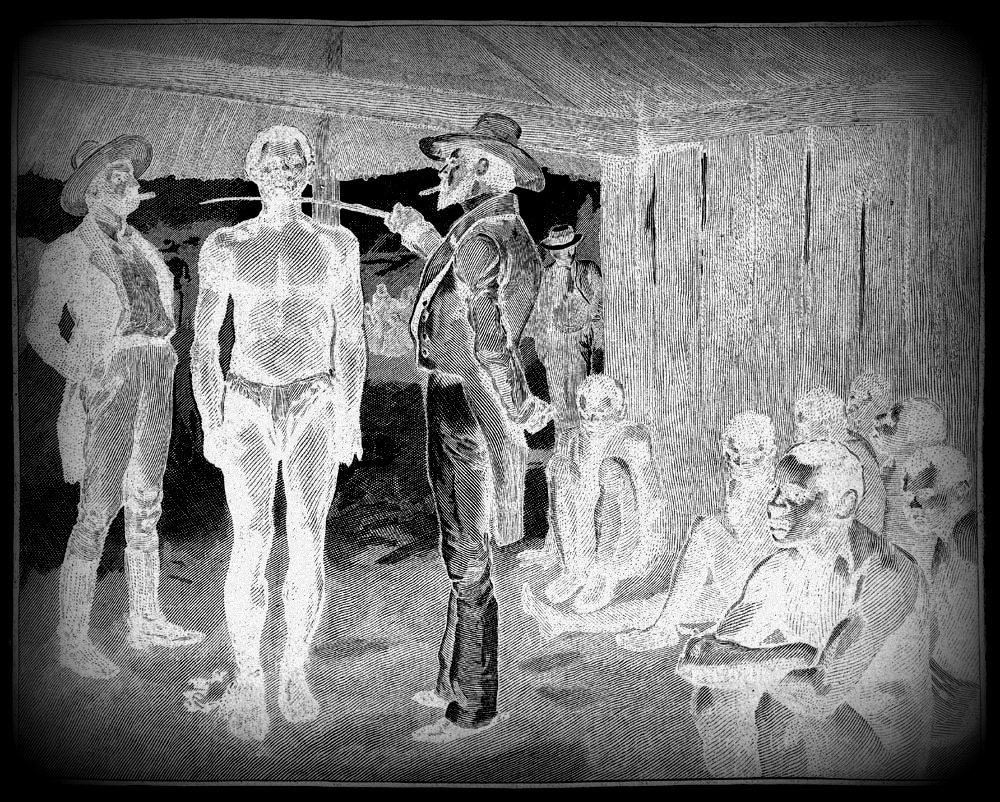

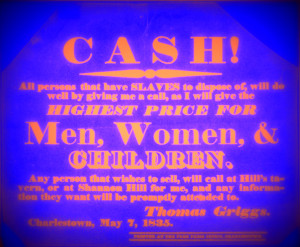

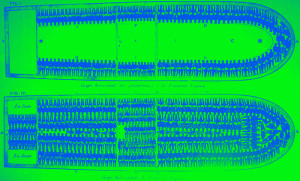

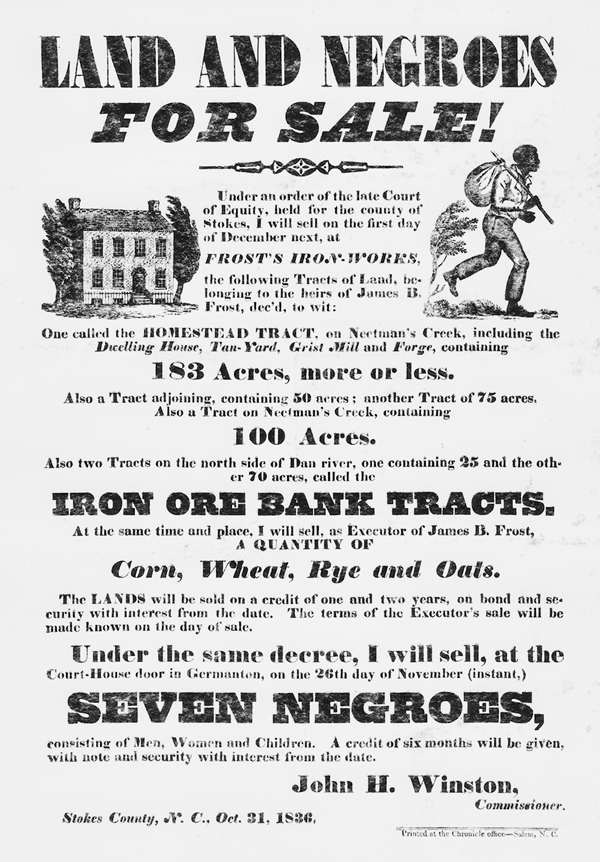

Slavery is illegal in every country in the world, but not so long ago it wasn’t. Emancipation was only 57 years old when my mother was born, and she remembers the community’s animosity for a woman known as “Granny,” because she had been a slaveholder. That community, by the way, was in the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia, the South’s breadbasket, and the place burned to the ground by General Sheridan’s Northern troops during the Civil War. These small farmers, Mennonites, Methodists, and United Brethren, which included my mother’s family, opposed slavery, and some opposed all war as well.

Slavery is illegal in every country in the world, but not so long ago it wasn’t. Emancipation was only 57 years old when my mother was born, and she remembers the community’s animosity for a woman known as “Granny,” because she had been a slaveholder. That community, by the way, was in the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia, the South’s breadbasket, and the place burned to the ground by General Sheridan’s Northern troops during the Civil War. These small farmers, Mennonites, Methodists, and United Brethren, which included my mother’s family, opposed slavery, and some opposed all war as well.

Imprimis I give to my son William Berryman Old Negro Jack and Grace and their ten Children and bob which in his possession and Sall which I delivered to him as part of his fathers estate some years past but being a little Negro girl, that attended me I desired my son William to let her stay and wait on me which is now with me, as also I give him Rachel and Nel & Beck their Mother, to him and his heirs and assigns forever and allso my fathers Old Silver Tankard without a lid and also my fathers coat of arms. Af (&?) als

Imprimis I give to my son William Berryman Old Negro Jack and Grace and their ten Children and bob which in his possession and Sall which I delivered to him as part of his fathers estate some years past but being a little Negro girl, that attended me I desired my son William to let her stay and wait on me which is now with me, as also I give him Rachel and Nel & Beck their Mother, to him and his heirs and assigns forever and allso my fathers Old Silver Tankard without a lid and also my fathers coat of arms. Af (&?) als o I give to my said son William Berryman all the lands I bought of Cossom Bennett in the County of Westmoreland which I have given him by a deed and do confirm to him his heirs and assigns forever.

o I give to my said son William Berryman all the lands I bought of Cossom Bennett in the County of Westmoreland which I have given him by a deed and do confirm to him his heirs and assigns forever.

, good will and good cheer and twelve dancing reindeer. It’s a time of beauty, joy, reverence, camaraderie, and all those fruit cakes.

, good will and good cheer and twelve dancing reindeer. It’s a time of beauty, joy, reverence, camaraderie, and all those fruit cakes. But did you ever stop to wonder where all these traditions come from? How our ancestors celebrated Christmas? Not just our grand- and great-grandparents, but those ancestors who came many hundreds of years ago and more. Did they go caroling? Did they make gingerbread houses? Did they hang stockings from the mantel? And why did there always seem to be an orange in my stocking?

But did you ever stop to wonder where all these traditions come from? How our ancestors celebrated Christmas? Not just our grand- and great-grandparents, but those ancestors who came many hundreds of years ago and more. Did they go caroling? Did they make gingerbread houses? Did they hang stockings from the mantel? And why did there always seem to be an orange in my stocking?

the moonlight. He got the idea to bring a small fir tree into his home, decorating it with candles lighted in honor of Christ’s birth. It’s a beautiful legend, but there is no evidence that it is true.

the moonlight. He got the idea to bring a small fir tree into his home, decorating it with candles lighted in honor of Christ’s birth. It’s a beautiful legend, but there is no evidence that it is true. months. Holly, with its fresh green leaves and bright berries, symbolized growth and fertility, the hope and reminder of renewal in the springtime to come.

months. Holly, with its fresh green leaves and bright berries, symbolized growth and fertility, the hope and reminder of renewal in the springtime to come.