I did not set out to write a multi-part series on the Blue Ridge Mountain evictions, but as the original post became longer and longer, I decided to split it into parts, all of which I will post in upcoming days. Be sure you read parts One, Two, Three, and Four.

My Blue Ridge Mountain Home Eviction: Part 5

The Blue Ridge evictions were not so long ago. They happened within the lifetime of my mother, who is still alive, though she is the last of her family. She was 14 when her grandparents had to leave their Blue Ridge home, but has only a few memories of the event.

As a girl, and before the evictions, she and her mother walked through Jollett Hollow and up the mountain to her grandparents’ home for visits. After the eviction, the walk was easier, just into Jollett Hollow.

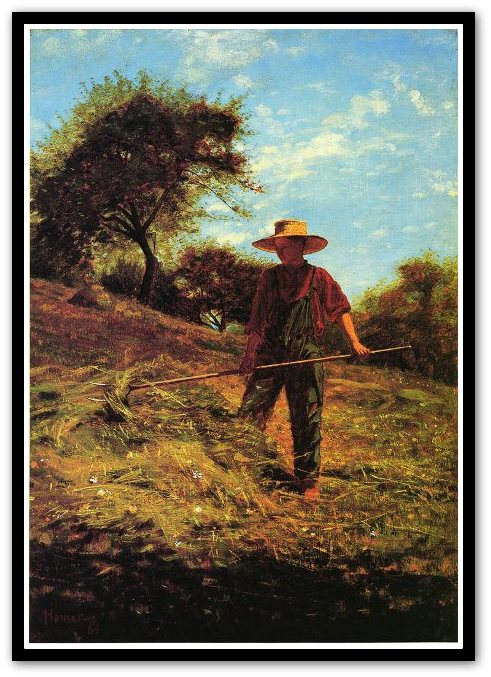

Her grandfather, Durret Collier, had a good amount of land. The Park records say 452 acres. In the spring, Durret and my mother’s father, Tom Merica, peeled the tanbark from their trees with a spudbar and hauled it to Cover’s tannery in Elkton. Durrett also managed a farm for a Mr. Moore, or Morris. These, to my knowledge, were his only sources of income.

My mother’s grandparents kept a busy house. As a young family, I can imagine the commotion on visiting day, with five daughters and one son. There must have been suitors aplenty! Later, with the girls grown and married, visiting day was still special. Aunts and cousins and neighbors came and went, some bringing casseroles or jelled salads, others sitting with plates of fried chicken or macaroni and cheese. Food was central to visiting, and a good host never got past “Come in” or “How are you?” without offering something nourishing.

With so many adults around, my mother sat quietly off to the side and listened to the grown-ups talk. She didn’t like playing with her cousins as much as she liked spending time with her mother, often coming in from play when there were visitors. She liked to hear what adults talked about, the community news, the gentle gossip that got her mother giggling.

She remembers some vague talk of the evictions, that her grandparents were pleased to be able to move to a better house to raise the young granddaughter who had been left in their care when her mother died. She remembers that others who talked with her grandparents were similarly pleased. Yes, she remembers some felt they were treated unfairly, but the impression she took away, filtered through these last 79 years, is that people thought it a net positive benefit to them.

I imagine their very first reaction was negative though, on hearing that the government was condemning their property and evicting them from their homes. Who would be happy about that? But time, and the offer of money, which was in short supply for most of these people, won in the end.

I imagine their very first reaction was negative though, on hearing that the government was condemning their property and evicting them from their homes. Who would be happy about that? But time, and the offer of money, which was in short supply for most of these people, won in the end.

Maybe those who went willingly are the minority. Or the majority. I don’t know, and probably never will. There are different levels of going “willingly.” But this I know: Not everyone was so pleased. A survey was taken in five hollows. Of the 132 families surveyed, 27 didn’t believe the park would ever exist, 17 were indifferent, four were hostile, ten showed anxiety, nine wanted to remain in the park, and 65 felt positive. Yet of those 132 families, 93 had no plan about leaving.

I can understand that, and I imagine the anxiety level was much higher than reported. Even under the best circumstances, moving causes stress and anxiety, and these were about the worst circumstances possible – eviction. Even if they did turn around to see it as a “net positive” as my ancestors did, I’m sure it wasn’t easy coming to terms with being forced by outsiders to leave their homes.

There was talk of violence. Some took the matter to court, hoping our legal system of checks and balances would prove the condemnation of their homes illegal. A cottage industry of books and college theses on displacement and the abuse of eminent domain sprouted up, many focusing on the loss of home and culture that these people suffered. Of course, there were also others that praised the efforts of Roosevelt and his New Deal to lessen poverty by moving subsistence farmers from marginalized lands to more fertile farms.

A 1930 census counted 150,659 subsistence farms in all of Appalachia. Of those, only about 465 were in the Blue Ridge, within the future park’s boundaries, and of those, 197 owned their homes or property. The rest were tenants, and a few squatters. Of those 197 owners, all were given cash buyouts and offered new homes outside the park boundaries, as were 93 non-property owners who were given moving allowances. These were mostly tenants or caretakers of mountain farms.

There were 104 families resettled by state welfare, and 67 who either relocated on their own or were granted permission to live out their lifetimes in their park homes. I know that only equals 461, and I don’t know what category the missing four families belong to, but those are the statistics I found.

Of all the land bought and deeded to the Federal government for the Shenandoah National Park’s creation, only seven percent was owned by the displaced residents. The vast majority of the land, 93 percent, was owned by people who would be considered outsiders; in other words, people who did not live within the future park’s boundaries, and a few who lived there, yet owned so much property as to be wealthy landowners and tenant holders who could easily move elsewhere, and did.

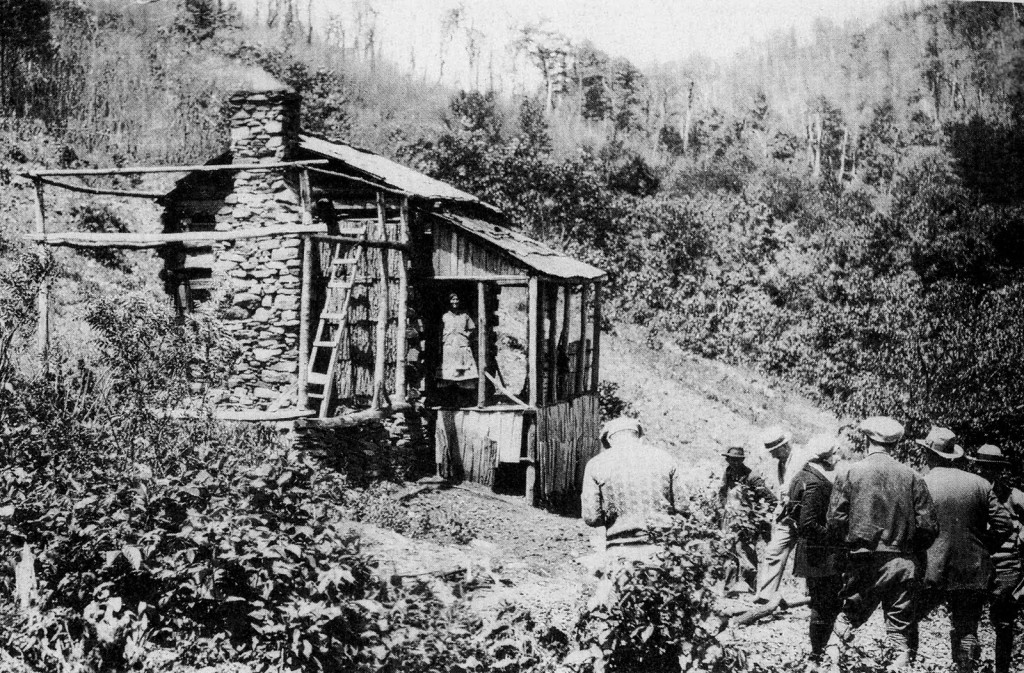

But what a seven percent that was. These were not just suburbanites whose first goal on moving into a new house is to move to a more expensive house.  These were families who had been there for generations. Many lived in compounds of extended families, with parents, brothers, grandparents all with their own small homes. Some were so poor that they couldn’t afford to move anywhere else. Each family’s circumstance was different, but I guess that every one of them was a complex tangle of emotions, needs, desires, and problems that had to be dealt with before they could pull up roots and leave.

These were families who had been there for generations. Many lived in compounds of extended families, with parents, brothers, grandparents all with their own small homes. Some were so poor that they couldn’t afford to move anywhere else. Each family’s circumstance was different, but I guess that every one of them was a complex tangle of emotions, needs, desires, and problems that had to be dealt with before they could pull up roots and leave.

But eventually, one way or another, all but a few of those families packed up and moved out, forcibly or voluntarily. They resettled, for better or worse, and lived out their lives, hopefully in peace and with love. They either bought or were given new homes, and they made do. That’s what we all do. We make do.

You can find Part Six of My Blue Ridge Mountain Home Eviction here. Or access the whole series here. To make sure you don’t miss the next installments, go to the “Subscribe” form at the top of this page.

lies and buried their old, and often their young too, in cemeteries just a few steps away. Midwives delivered babies, herbalists consulted on medicine, and occasionally, the fortune teller up in the woods near Waynesboro read nervous young women’s futures.

lies and buried their old, and often their young too, in cemeteries just a few steps away. Midwives delivered babies, herbalists consulted on medicine, and occasionally, the fortune teller up in the woods near Waynesboro read nervous young women’s futures.

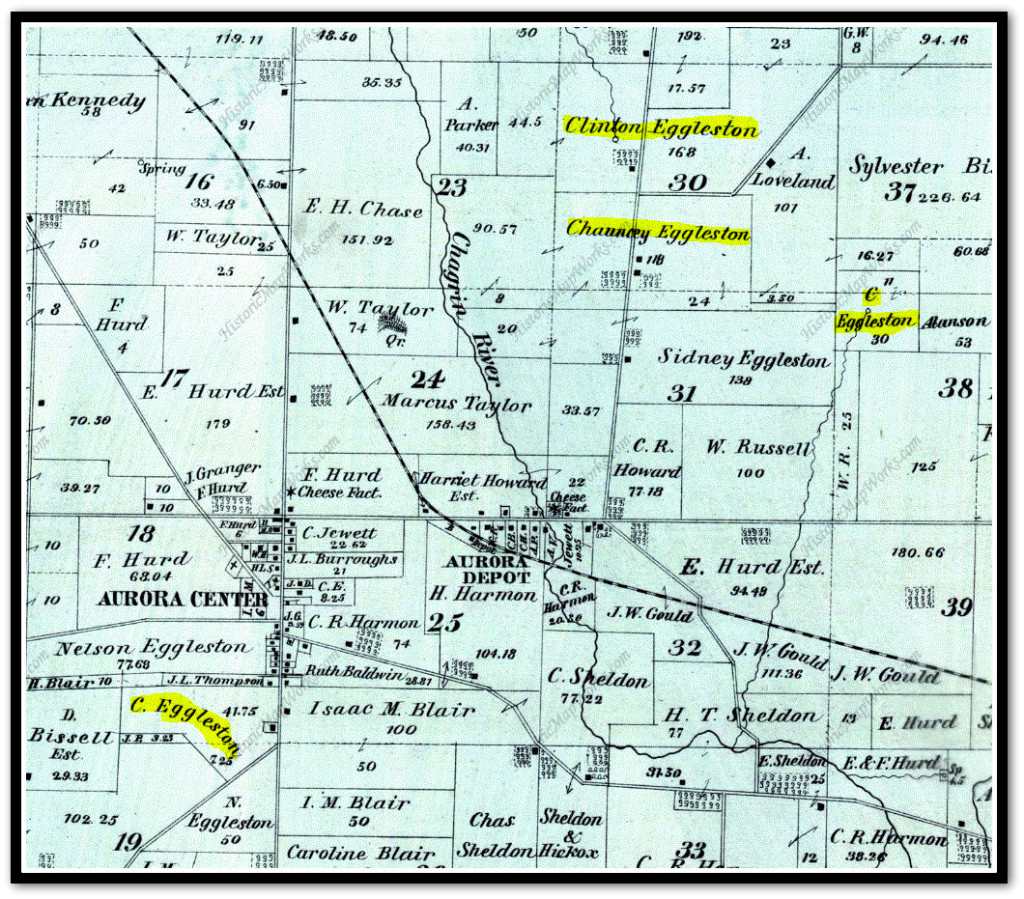

village founded by his forebears, who walked with their wagons hauled by teams of oxen from Connecticut across the rugged, nearly impenetrable Allegheny mountains and into the wild frontier of New Connecticut, as the Ohio territory was called, in 1807.

village founded by his forebears, who walked with their wagons hauled by teams of oxen from Connecticut across the rugged, nearly impenetrable Allegheny mountains and into the wild frontier of New Connecticut, as the Ohio territory was called, in 1807.

I don’t know Clinton’s reasons. Francis wrote simply that his father was “conservative in methods.”

I don’t know Clinton’s reasons. Francis wrote simply that his father was “conservative in methods.”

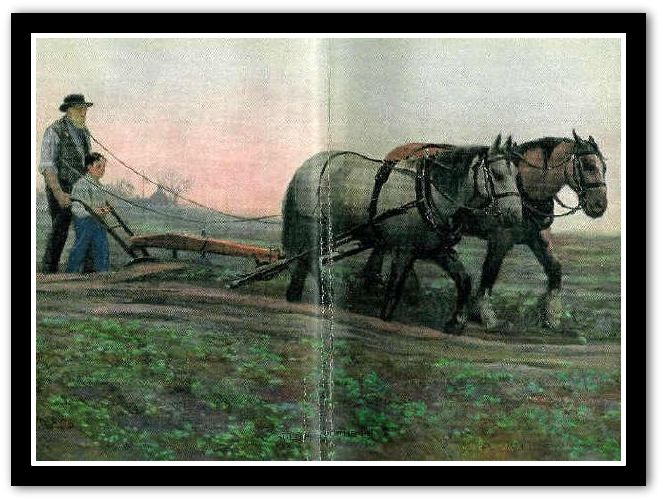

Just an adolescent, he was sent to split timber into “rails, 12 feet long and perhaps five inches square,” and to put his muscle behind “a great wood pile which was cut by horse-power and drag saw and split and corded by man and boy power.”

Just an adolescent, he was sent to split timber into “rails, 12 feet long and perhaps five inches square,” and to put his muscle behind “a great wood pile which was cut by horse-power and drag saw and split and corded by man and boy power.”

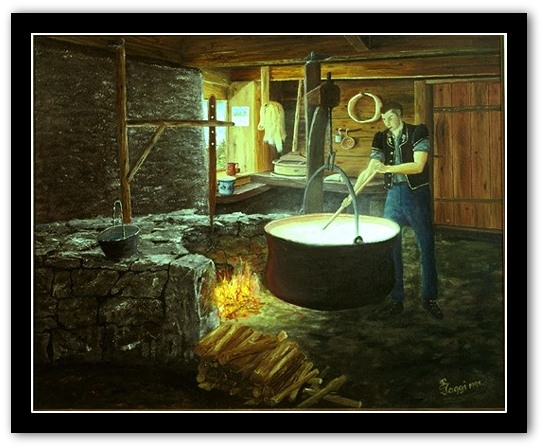

Francis helped produce all the chief products of the farm, which were milk, butter, cheese, and sugar; and to sow, grow, hoe, and harvest the field crops, which were hay and corn to feed the cows, and oats for the horses.

Francis helped produce all the chief products of the farm, which were milk, butter, cheese, and sugar; and to sow, grow, hoe, and harvest the field crops, which were hay and corn to feed the cows, and oats for the horses.

I began this story saying that Francis Eggleston often found himself in the wrong place, doing the wrong thing, or more specifically, the wrong thing for his temperament and interests.

I began this story saying that Francis Eggleston often found himself in the wrong place, doing the wrong thing, or more specifically, the wrong thing for his temperament and interests.