Imagine yourself as fresh to the world as Adam or Eve. What a wondrous place you inhabit, full of beauty and mystery. Like a child, you wander free, examining every thing, curious about every leaf and insect, rock and rivulet. But the insect bites you, and it hurts. You want to know why it did that, and lacking any other explanation, you decide it must be angry. Then it rains, and you are drenched and cold.  You don’t know why that happened, and so decide the skies must be angry.

You don’t know why that happened, and so decide the skies must be angry.

And then the leaves begin to fall off the trees, and they keep falling, day by day, until none are left. Your world is becoming colder, darker. The sun sinks lower into the horizon every day. Whatever or whoever is behind this, you think, must be in a very bad mood. Nothing else could explain it.

As the light fades a little faster each day, you become afraid. What if the sun goes away altogether, leaving you in darkness? Will the sun come back? How can you make the sun come back? Please come back!

For those who lived before astronomy, mathematics, and physics came to explain nature’s secrets, the world was beguiling, unpredictable, and often frightening. There were no scientific explanations for the movements of the sun or the turning of the seasons. Weather patterns that change day to day often seemed fickle, without pattern or reason. And so the people ascribed those acts to gods who had human-like moods and tempers. Nothing else could explain nature’s behavior.

What we take for granted about the natural world today was not yet known. That the earth, for instance, circles the sun, held in orbit by powerful gravity.  Or that the seasons are determined by the sun’s position relative to earth. The sun, we know, grows weaker in the winter and stronger in the summer for those of us in the northern hemisphere because of the tilt of the earth’s axis.

Or that the seasons are determined by the sun’s position relative to earth. The sun, we know, grows weaker in the winter and stronger in the summer for those of us in the northern hemisphere because of the tilt of the earth’s axis.

But early cultures did not know these things. They lived at the mercy of nature. And so they created religions that sought to erase the unknown and give their followers a sense of control over their world by creating gods that ruled these otherwise inexplicable natural phenomena.

Lacking scientific reasons to inform them why the sun comes up and goes down each day, or why the rains suddenly cease and the lands dry up, the people decided that gods were behind these acts of nature. When gods were happy nature cooperated with the needs of man. When the gods were angry people might starve.

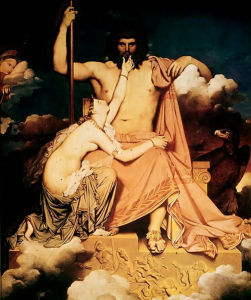

Zeus, supreme god of the Greeks, threw thunder bolts when angry. He changed the seasons and shaped the weather according to his temper. The Germanic Goddess Gefjun plowed the land and brought abundance and prosperity. Apollo, god of sun and light, drew his chariot across the sky by a team of celestial horses, driving the sun in its course.

The Germanic Goddess Gefjun plowed the land and brought abundance and prosperity. Apollo, god of sun and light, drew his chariot across the sky by a team of celestial horses, driving the sun in its course.

These beliefs created order in the people’s worlds, if not always predictability. They could create more predictability, they thought, and better design nature to their needs, if they pleased the gods. And so they prayed and created elaborate rituals and festivals to honor the gods.

Across nearly every culture one of the most important deities was the god of light and sun. The sun ruled their worlds, and so the people took effort to worship and placate their sun gods. The winter solstice was perhaps the most important celebration, the time when the sun no longer sank into a lower arch every day and instead began to rise again, winter’s light no longer growing shorter every day, but lengthening into spring and then summer. Only then did they know their gods were happy and that the days would not continue to shorten until there was only darkness.

But they could not trust that the solstice would always return. They knew their gods were fickle. And so when the days of fall shortened into winter, after the harvests were in and the leaves fallen from the trees, when the cold crept into living spaces and clouds obscured the sun, people of ancient times called up their gods and spirits to ensure spring’s safe return. The sheer power of their rituals, they believed, could miraculously transform gathering dark into lengthening light.

The day of their rituals, the day when the sun started its rise up the horizon once more, fell and still falls, depending on positions of the planets, between December 20 and 23 every year in the Northern Hemisphere. On that day, the winter solstice, people from the North — ancient Rome, Scandinavia, Persia, Germany, China, North America — celebrated the sun’s new path higher into the sky.

On the solstice the sun halts its southward journey, pauses for a moment, and then starts moving northward. The Scandinavian and British people gave the name Yuletide to their winter solstice celebrations. “Yule” means “wheel” or “whole,” and “tide” means “time.” Yuletide, then, is the time of wholeness, or holiness. Germanic people called the solstice “weihnachten,” which means “the holy nights.” For them, and for the earth, it was a time of deep rest. A time of peace and reverence. The old year ends, its journey complete, its duties fulfilled. Now the sun can begin its journey up the sky again, bringing new birth, new life.

In some cultures it was a day of of feasting, merrymaking, and exchanging gifts. In others it was a day for quiet and reflection. In Scandinavia the people lit giant bonfires that symbolized the birth of the light of life, afterwards bringing into their great halls the yule log to burn during the twelve days of holy time. They brought “trees of life” into their homes and placed a star at the top to represent the light of life.

In Rome master and servant switched roles, the master serving the servant. The Romans lit candles and brought evergreens into their homes. Their festival, called Saturnalia, led right into Dies Natalis Solis Invicti, or the Birthday of the Unconquered Sun, which was celebrated with a solemn festival of lights on December 25.

In Rome master and servant switched roles, the master serving the servant. The Romans lit candles and brought evergreens into their homes. Their festival, called Saturnalia, led right into Dies Natalis Solis Invicti, or the Birthday of the Unconquered Sun, which was celebrated with a solemn festival of lights on December 25.

How easy it was for Christianity to assume that date to celebrate Christ’s birth, exchanging worship of the sun for worship of the Son! Many, maybe most Christian scholars believe this theory to be true. Indeed, no less than the Catholic Encyclopedia flat out says: “The true birth date of Christ is unknown.” And Catholic World states clearly,

“No one supposes or has ever supposed that [December 25] was His actual birthday.”

As for the origin of December 25 as the day of celebrating Christ’s birth, Catholic Encyclopeida goes on to say,

“The same instinct which set Natalis Invicti at the winter solstice will have sufficed, apart from deliberate adaptation or curious calculation, to set the Christian feast there too.”

Which means that both worshipers of the sun and worshipers of Christ believed the winter solstice, and particularly the sun’s birth day, was a fitting time to worship and celebrate, in once case the Sun, in the other, the Son.

The Bible does not mention the date of Christ’s birth, and gives few clues. What clues there are tend to point against December 25 as the date of the blessed event. What’s more, since celebration of birthdays was considered a pagan practice by early Christians, no mention at all is made in early Christian texts of celebrations honoring the birth of Christ. One early scholar even mocks Roman celebrations of birth anniversaries, calling them pagan practices.

It wasn’t until more than three hundred years after the birth of Christ that the first Christmas celebration was recorded, in a text written by an Egyptian teacher far from Judea. It was the time of Constantine, Emperor of the Roman Empire.

Constantine had been a worshiper of the sun god Apollo, but on the day before a key battle he had a vision of a bright cross inscribed with the words, “hoc signo vince,” meaning, “in this sign conquer.” Jesus appeared to him in a dream that night telling Constantine to use the cross on his war flag.

Thus began the reign of the first Christian emperor of the Roman Empire, which spread under his rule from western Asia to Britain,  encompassing cultures that had been in battle with each other for hundreds, if not thousands of years.

encompassing cultures that had been in battle with each other for hundreds, if not thousands of years.

To maintain his grip on the Empire Constantine needed to ensure peace among these former enemies. He would do it, he decided, through Christianity, and so began his crusade to spread the Gospel far and wide.

That included issuing an edict granting everyone in the empire the freedom to practice their religion, followed by a second edict proclaiming Christianity as the official religion of the Roman Empire. He did this not out of piety, but out of political ambition, wishing to spread peace throughout his empire through the word of the Gospel, and to expand his empire through Christianity’s growth. In fact, Constantine was something less than pious, even having his wife and son murdered because he feared their treachery, and persuading his people to adopt Christianity under threat of death.

Priests, too, had their roles, one of which was to convert the masses of pagan idolaters to Christianity. One tactic they used was to superimpose Christianity over existing pagan holidays, including the festival of the winter solstice, Saturnalia, and the Dies Natalis Solis Invicti, or birthday of the unconquerable sun. In Northern Europe the twelve days of Yuletide were reinterpreted as Christian.

The priests made the ceremonies quieter, more solemn, by holding a mass on the feast day, called “Christ’s mass.” They also reimagined the Saturnalian practice of giving gifts to symbolize the gifts given to Christ by the three wise men.

All across Europe and Western Asia Christianity slowly absorbed the ancient traditions, made them its own. The old gods disappeared, replaced by the one holy God and His Son.

The holy day — holiday — celebrations remained, wrapped now in the shining Light of Christ and all that is whole and holy. There is peace, joy, renewal in that Light of Lights; remembrance, reverence, and the reminder that we are all, whatever our beliefs or creed, of this earth, together. The new sun is born. The new Son is born. Ancient, pure, life-giving, forgiving, embracing, beloved.