I did not set out to write a multi-part series on the Blue Ridge Mountain evictions, but as the original post became longer and longer, I decided to split it into parts, all of which I will post in upcoming days. Be sure you read parts One, Two, Three, Four, Five, Six, and Seven.

My Blue Ridge Mountain Home Eviction: Part 8

Memory is a trickster, always pulling pranks and distorting what we think we know.

When I was a tiny girl, no more than four years old, I remember our family driving from San Diego to Chavez Ravine in Los Angeles to see one of the first Dodgers games since they  left Brooklyn.

left Brooklyn.

Ours was a baseball family, so I already had a sense of what was happening on the field, with balls being hit and caught, players running this way and that.

But then something out of the ordinary caught my eye. A baseball player started to run from the field toward his dugout, and as he did, fans from the stadium poured over the wall and onto the field, chasing, then mobbing him.

I asked my father what was going on, and he explained that the man was a famous baseball player, Jackie Robinson, who would not be playing anymore, and people loved him and wanted to say thank you, and goodbye.

I’ve told that story many times. Then, about a year ago, I mentioned it to my brother, who was also there. He’s ten years older than I am, so would have a much better memory of the event.

But instead of corroborating my story, he said, “Un-uh, you weren’t there. That’s my memory,  you heard me tell the story and then remembered it as though it was your own.”

you heard me tell the story and then remembered it as though it was your own.”

Is he right? He thinks so. Am I right? I certainly feel right, the memory is that vivid.

Is it my memory? I hope so. But I can’t guarantee it is. That’s a bit unsettling, and in some part I wish my brother had not challenged me. It would have been easier that way. I don’t like the confusion I have now where once I had a treasured memory and an interesting story.

Memory is a funny thing. It doesn’t stand still. It changes in ways so small that we don’t know it’s changing. Details blur, and so do causes. But never mind those, it’s the meaning of the memory that matters, not the accuracy of details.

We may forget exactly what happened on 9/11, the sequence of events, the hour of day, but we will never forget its significance. Or we might remember the events so vividly that our trickster memory convinces us we were there.

It’s called the illusion of truth, or confabulation, and it is what may or may not account for my Jackie Robinson story.

Silent film actress Mary Pickford once recalled her fear when filming a scene alongside alligators. But she wasn’t there. The alligators were shot separately and that film was run as a background to her scene.

Ronald Reagan several times talked about when he filmed the liberation of Nazi concentration camps as it was happening, in Germany. But the closest he ever got was making World War II training films in Hollywood.

Both of them confused their own experiences with the vividness of the event in our collective memory.

I have a similar memory of the Blue Ridge mountain home evictions for the making of the Shenandoah National Park. Not that I was there. The sensation isn’t that strong. But I feel it in the same way that some other descendants of the evictees do, of the emotions that tore at our ancestors. Almost as if we ourselves were evicted.

I feel the pride of place, that they lived somewhere so special that the government wanted to make a park of it.

I understand the anger of being told they had to leave their mountain home, to give up their property against their will.

I have the tinge of shame at how people came to view these mountain folk after the media and social workers portrayed them as hillbillies, illiterate and slovenly, instead of independent, self-reliant, and true to our pioneer heritage.

And finally, I feel the comfort and happiness my grandmother got from her new home, nearer her family and in a community of friends.

Are all these feelings valid? Of course. But are they accurate? No. No memory is perfect, no retelling of an event is the complete truth. We mean for it to be. But our trickster memories have been at work.

We are influenced by events of intervening years, accounts told by others, the happy person’s tendency to remember only the positive, the depressed person’s tendency to remember only the negative, and a host of other memory tricks that work to distort everything we think we remember as the truth.

I’m lucky. I “remember” through what my mother tells me; that my great grandparents were at peace, even happy about leaving the mountain. That’s the memory I carry, and so I’m at peace with the Park.

Some descendents aren’t so lucky. They carry a more troubled memory of the evictions, and I can understand why.

If I knew my ancestor was bitter, it would not be so easy to have a good memory of the Shenandoah National Park’s creation. Being loyal to the blood, I would feel outrage at my ancestor’s treatment, and frustration at not being able to correct it, even decades after they are dead and gone. It would be an affront to me, to my blood.

How does someone with a bad family memory of the park’s creation shed themselves of those feelings? I don’t know. And should they?

Many times anger comes from powerlessness, the inability to do something about a problem. So some descendants have taken action, working with the Park to ensure that our ancestors’ histories are told to Park visitors, and told in the right light; building memorials outside the Park, maintaining Park-land cemeteries.

So some descendants have taken action, working with the Park to ensure that our ancestors’ histories are told to Park visitors, and told in the right light; building memorials outside the Park, maintaining Park-land cemeteries.

I would also want markers where some of the homes or communities were, and to see that graveyards are kept neat. That’s about all we can ask.

I applaud those who feel they need to do so for taking action. It takes commitment.

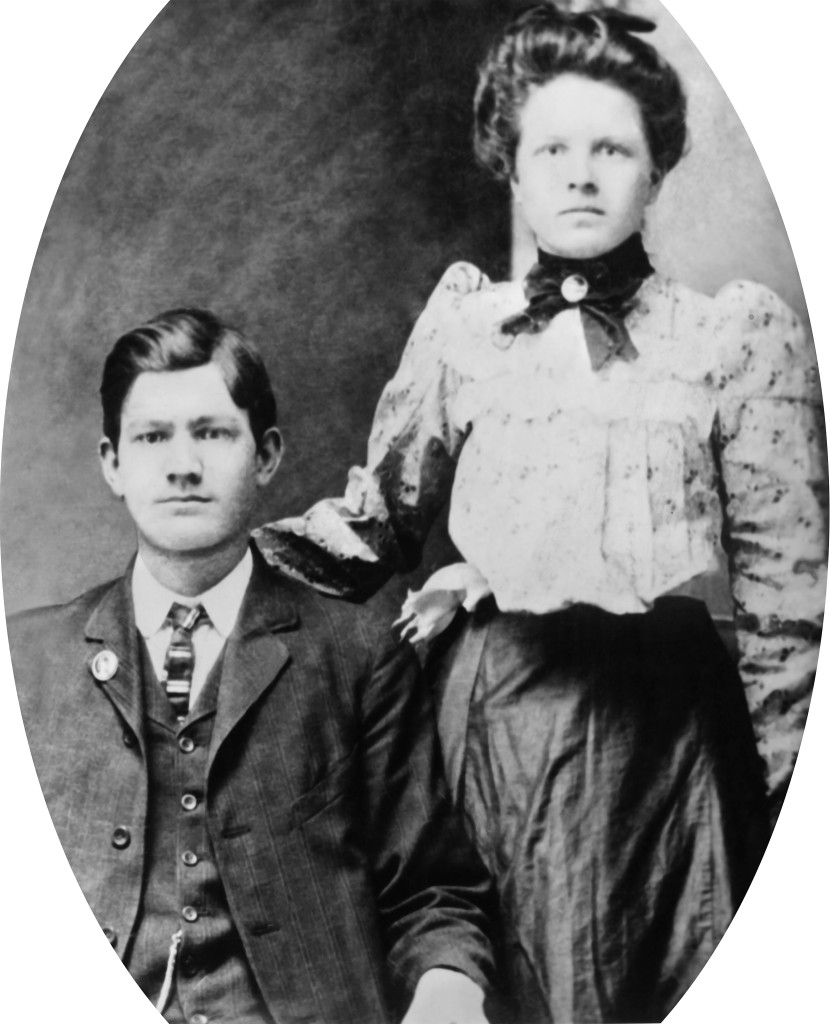

The strength of these people’s ancestral memories is a phenomena I haven’t experienced before. The bond these Blue Ridge evictees’ descendants have with their ancestors is remarkably raw, fresh.

To compare, on my father’s side I can trace my family back to the first (non-Native) settlers in America. I’ve been to New England and seen the houses they lived in, the meeting houses and churches they filled with their voices, the plaques that engraved my ancestors’ names in history. It was exciting, thrilling even, but it did not captivate me as these bits and shards of Blue Ridge family history have. I did not feel their experience.

Perhaps, like an unburied body, there is something unsettlingly undone in the Blue Ridge. Perhaps those homes that were vacated, suddenly and on someone else’s terms, eventually crumbling without their families, or being torn down, haunt us with that sense of unfinished business, that lack of closure.

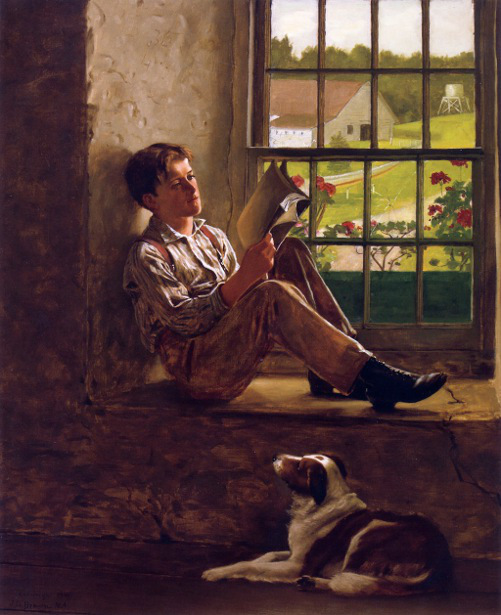

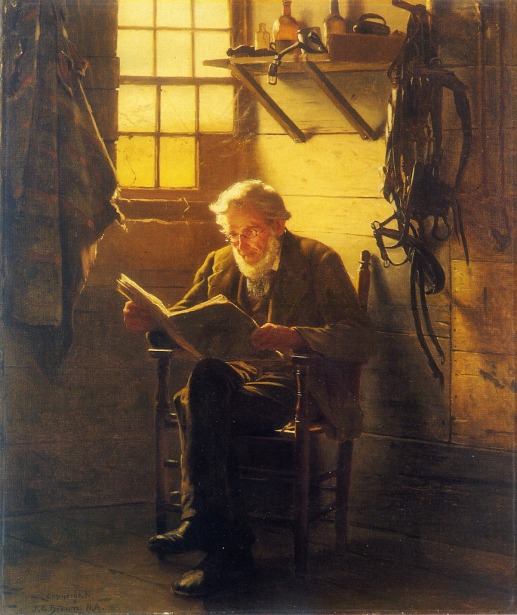

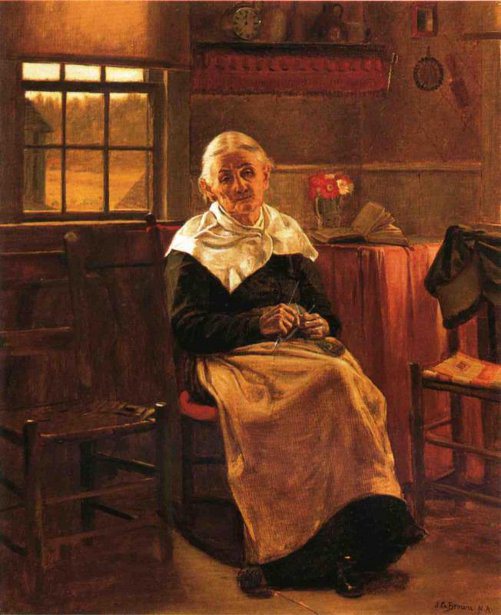

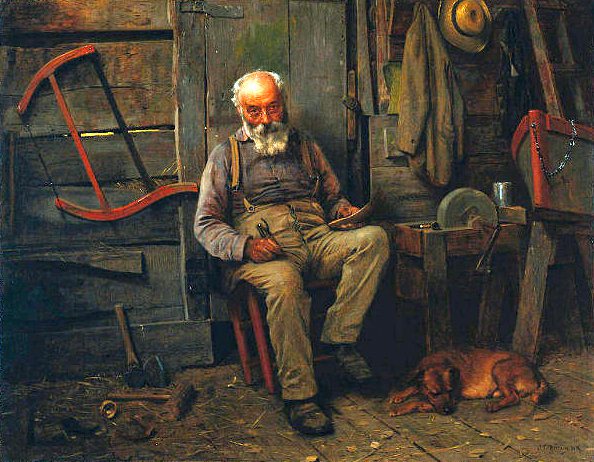

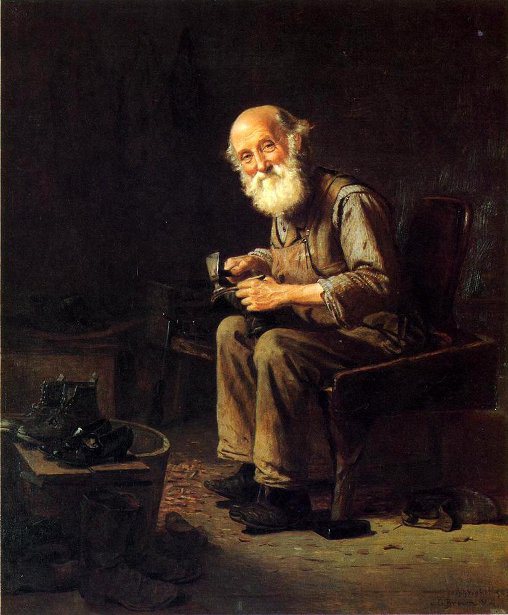

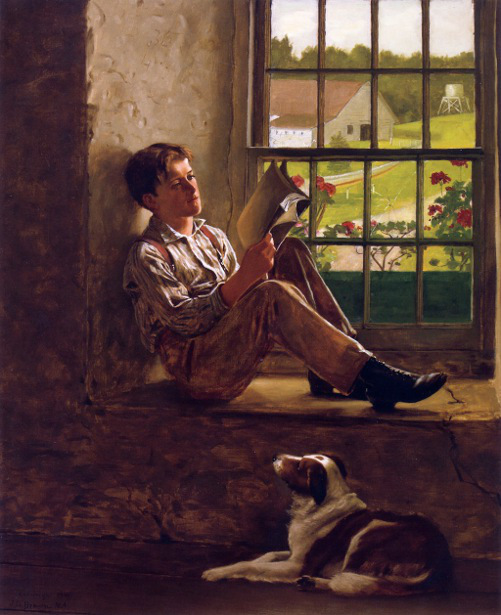

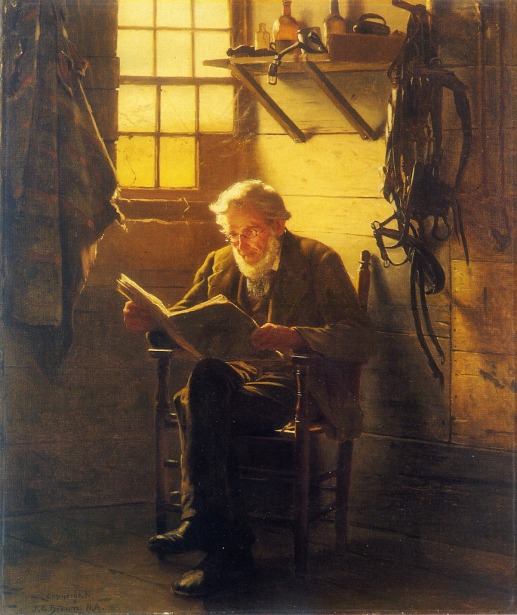

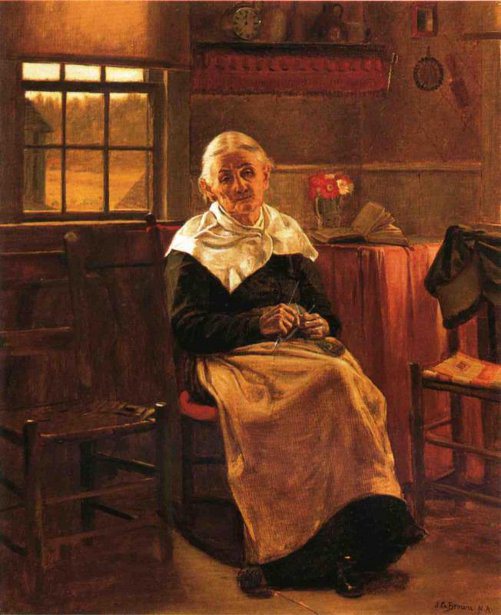

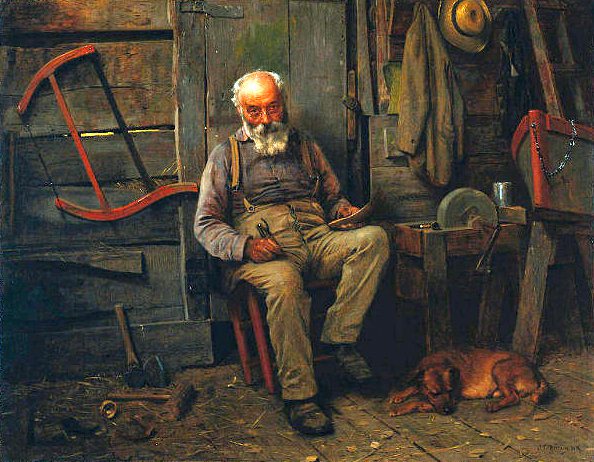

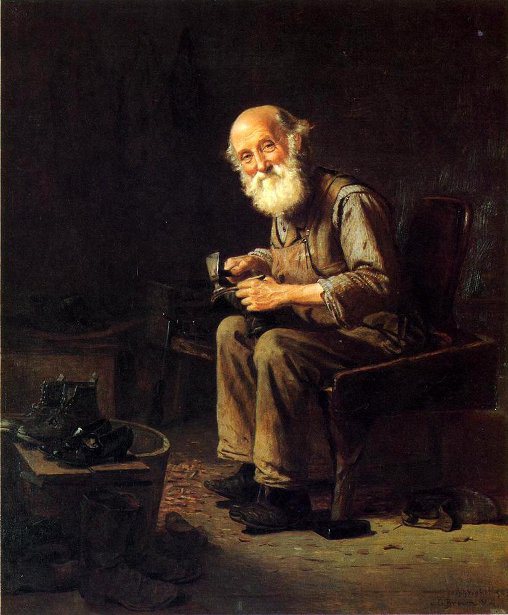

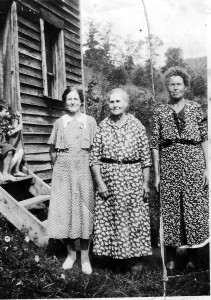

Or maybe we see that time has stood still in the Blue Ridge. With no subsequent development, and with the mountain woods and meadows remaining untouched, we can almost see our ancestors in their daily work, their farming and cooking and hunting, their mending and fixing and building and tending to children.

We see the trails they took to go “a’visitin'” or to church. We see those old photos from the National Archives that let us look right into the kitchens and living rooms of our  ancestors, and we can almost see ourselves right there beside them, conversing in their ancient language, living between our time and theirs.

ancestors, and we can almost see ourselves right there beside them, conversing in their ancient language, living between our time and theirs.

Or perhaps it’s these mountains themselves, haunting and lovely, creaking with age and whispering the secrets of our ancestors in every breeze.

I don’t know what memory binds me here, but whatever it is, it has me. The Blue Ridge and her people are beating in my blood, beating in my heart, and for that connection I am grateful.

Like this:

Like Loading...

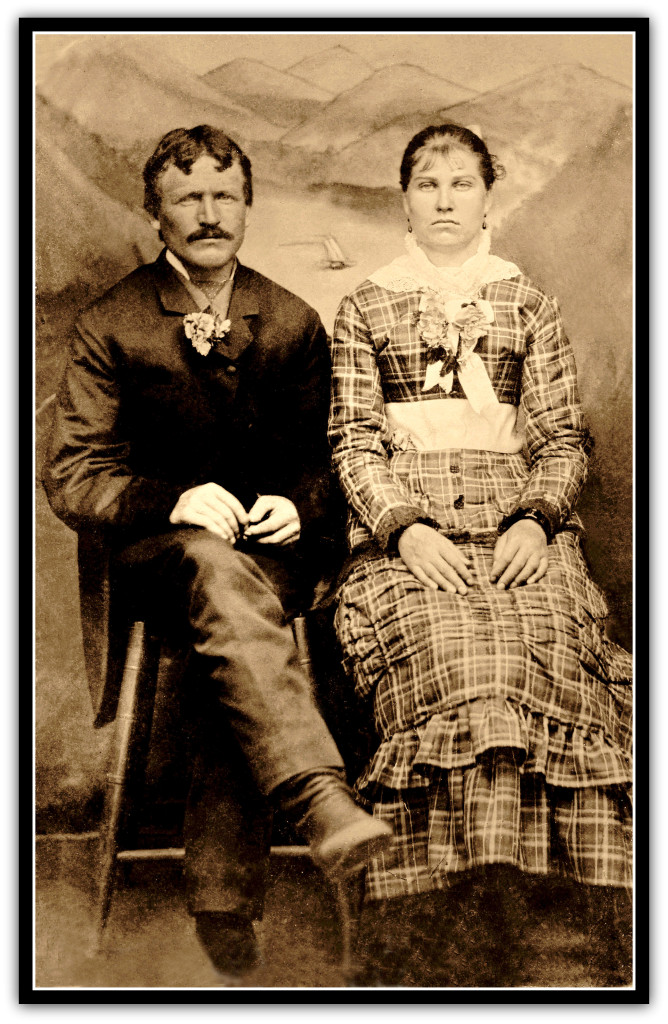

The Blue Ridge Mountains got themselves into the blood of five generations of my ancestors.

The Blue Ridge Mountains got themselves into the blood of five generations of my ancestors.

in the 1700s: Francis Meadows and his wife, Mary; and Martin Crawford and his wife, Elizabeth McDonald.

in the 1700s: Francis Meadows and his wife, Mary; and Martin Crawford and his wife, Elizabeth McDonald. McDaniel, and David Turner and Catherine Lucas.

McDaniel, and David Turner and Catherine Lucas.

left Brooklyn.

left Brooklyn. you heard me tell the story and then remembered it as though it was your own.”

you heard me tell the story and then remembered it as though it was your own.”

So some descendants have taken action, working with the Park to ensure that our ancestors’ histories are told to Park visitors, and told in the right light; building memorials outside the Park, maintaining Park-land cemeteries.

So some descendants have taken action, working with the Park to ensure that our ancestors’ histories are told to Park visitors, and told in the right light; building memorials outside the Park, maintaining Park-land cemeteries.

ancestors, and we can almost see ourselves right there beside them, conversing in their ancient language, living between our time and theirs.

ancestors, and we can almost see ourselves right there beside them, conversing in their ancient language, living between our time and theirs.

But for the tenants, I’m not so sure. I lived many years in rentals before buying a home. Renters have few rights, no matter where you are. That’s simply the way it is, dehumanizing as it may be.

But for the tenants, I’m not so sure. I lived many years in rentals before buying a home. Renters have few rights, no matter where you are. That’s simply the way it is, dehumanizing as it may be.

They are gentle, welcoming, not at all intimidating, as are our Sierras that separate California from the rest of the country like a knife edge.

They are gentle, welcoming, not at all intimidating, as are our Sierras that separate California from the rest of the country like a knife edge.

There is a profound silence telling you that secrets hide here, covered by mists and time and the forests that reclaim their pristine past.

There is a profound silence telling you that secrets hide here, covered by mists and time and the forests that reclaim their pristine past. Of the Blue Ridge, he wrote:

Of the Blue Ridge, he wrote: And of Shenandoahans, he wrote:

And of Shenandoahans, he wrote: I couldn’t agree more.

I couldn’t agree more.