October is peak tourist season in Shenandoah National Park, when the forest puts on a dazzling show that never fails to delight.

October is peak tourist season in Shenandoah National Park, when the forest puts on a dazzling show that never fails to delight.

The trees are decked out in their royal colors: crimson, gold, and purple, a palette of shimmering color that stretches from far horizon to browning fields below.

Winged seeds fly on the wind, leaves too, falling to let their trees’ bare bones bask in misty sunlight through the winter.

Tourists flock to the mountains, their cars a slow-moving chain along Skyline Drive, cameras like attachments to their faces clicking every adorned vista.

Hikers scuff through the woods, their irreverent voices ringing through trees, their hiking boots crackling leaves underfoot.

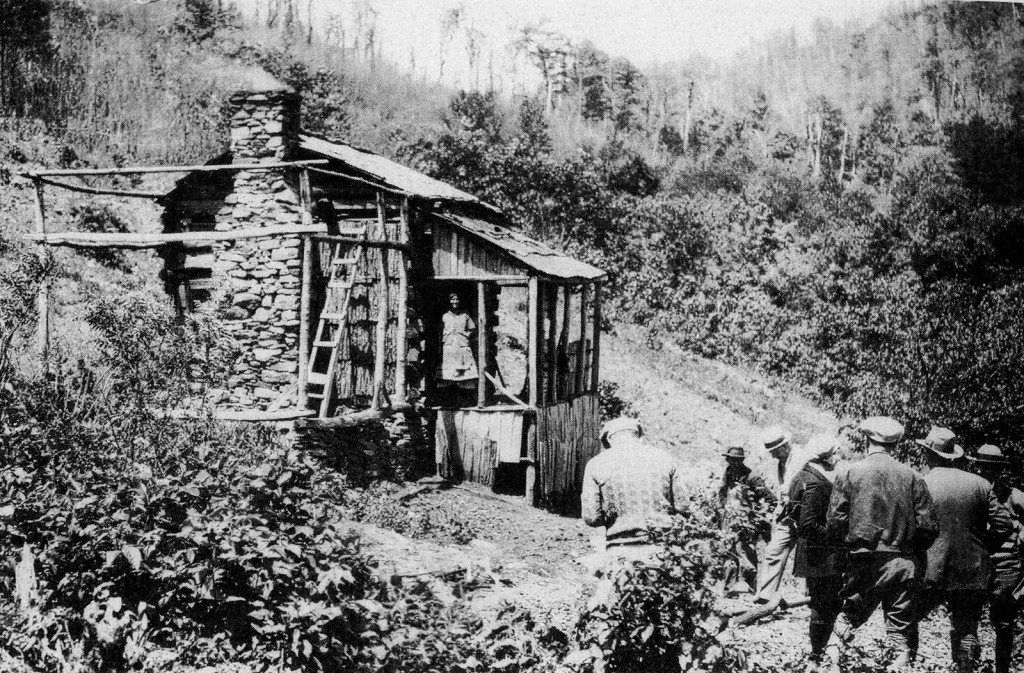

Here and there they come across an old mossy wall, the rough foundation of a home long gone, or a graveyard barely visible through the bramble.

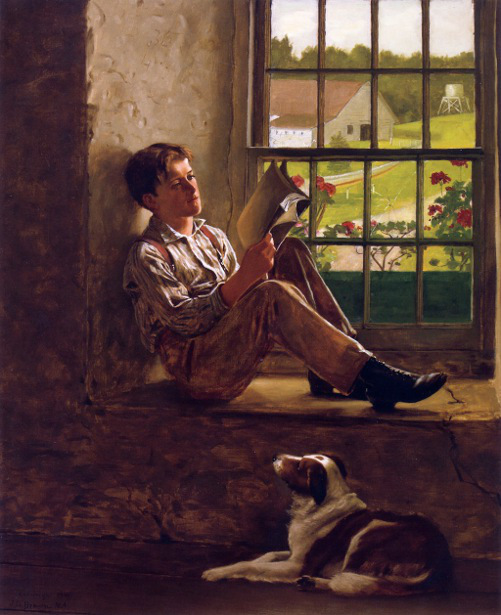

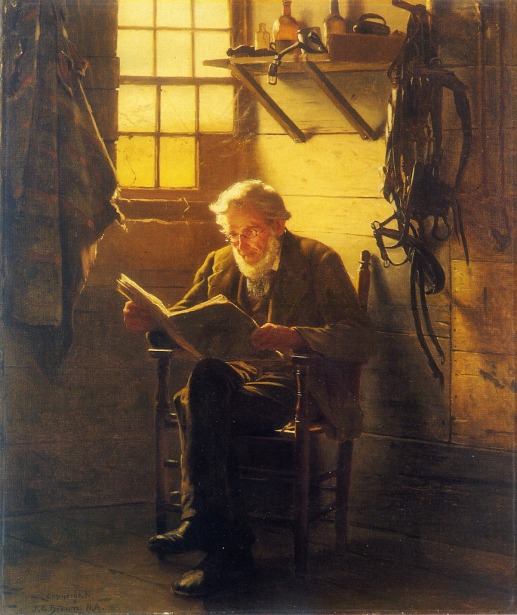

Each of those are testament to a time forever lost, a time when the mountains rang with voices of a different kind, the voices of people whose homes and barns and cemeteries these were. People who tended gardens, pastured their cattle, built schools and churches, and lived full lives in these mountains, most for generations.

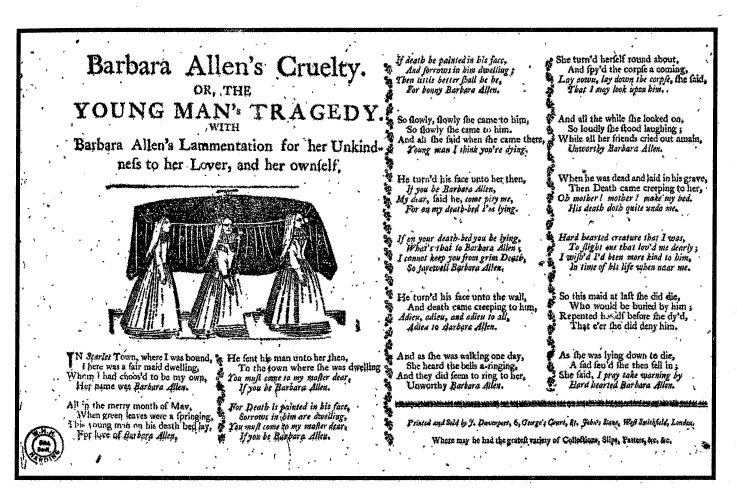

In the mid-1700s they started to come, traveling south on the Great Wagon Road from Pennsylvania to Shenandoah. Settlers were quick to take up the fertile bottom land of the Valley. Latecomers of necessity moved further and further up the mountain, laying claim to every bit of clearable land and making do with what they could find.

For 200 years those generations eked out their living from the rough soil and rugged mountains.

For 200 years those generations eked out their living from the rough soil and rugged mountains.

Now they are all gone, the forest abandoned to its wild ways and the few intrepid hikers who venture from their cars into those deep woods.

In 1934 they began to leave, some of their own accord, others not, when government used the power of eminent domain to clear land for Shenandoah National Park.

Some walked down the mountain without a glance back, never to return. Others were dragged away, literally thrown from their homes, their doors barred by police against any thought of coming home.

It was a nasty business, and one the bureaucrats were loath to take on. But they had jobs to perform, objectives to achieve, and the mountain people were unfortunately in their way. That was the cold truth.

At one time tens of thousands lived in those mountains. But when the thin topsoil was spent, the trees harvested and hills nearly bare, many left.

By 1934 only about 7,000 remained in 250 square miles. But seven thousand is a lot of people to relocate, especially considering nearly all had

to be coaxed or moved reluctantly from their homes, some kicking and screaming.

This is the dark past of Shenandoah National Park.

A few who were evicted are still alive, although they were mere children then, their memories foggy now, unreliable in the details of their stories, but clear enough to tell of heartless government agents, and of negative depictions that painted them as slovenly, mentally deficient, sub-normal.

There are others who were not yet alive back then and heard the stories from their parents and grandparents. Some of these descendants are encyclopedic in their knowledge of the evictions. Others have distilled their families’ stories down to pure resentment, discarding details and facts, leaving only anger. The bitterness is carried down from father to son, mother to daughter, and in many, it is still palpable today.

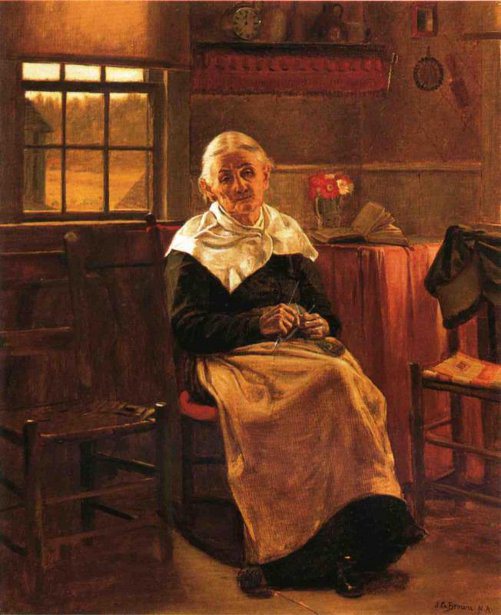

The stories resonate. There was Lissie Jenkins, five months pregnant, who sat her rocking chair and would not move, and so was dragged out, rocking chair and all. I’ve imagined her fear of the unknown after most of a lifetime on that mountain; how losing the security of that place may have been more than she could emotionally bear. We are not all adventurers. We do not all look at an unknown future with the optimism of opportunity, but instead, cling to our chosen rocking chair as if it alone holds us to this earth.

I’ve thought of John Mace, who watched the police stack his furniture in front of his house and set it all afire, his soul no doubt smoldering as the flames engulfed all the physical evidence of his life.

What could he have felt but seething fury at such an act? And what could his neighbors feel but fear and distrust, knowing they would be next if they did not cooperate? Of course with such acts the government became the enemy to many.

I’ve thought of John Nicholson, who was accused of theft after taking the windows from his father’s home, a home that was set to be torn down.

Of Lillie Herring, also accused of theft from her own home, who wrote with proud indignation to officials, “I am not lieing on no one and I’m not telling you one ward more that you can prave and I am living up to what I say.”

And of of Elmer Hensley, who made the simple request to take down his cabin, one log at a time, so he could rebuild it on land outside the Park boundaries. The simple request was denied, with no explanation given.

These acts stink of the meanness and arrogance of some agents, and form the mythology that surrounds the evictions, that they were indeed historic criminal acts by a tyrannical government.

Were they?

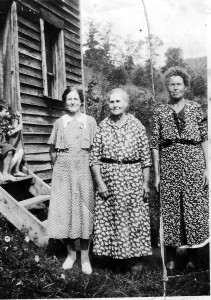

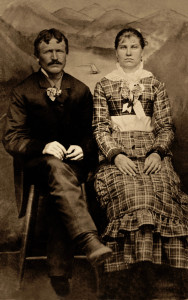

My great-grandparents as well as countless cousins, aunts, and uncles were  among those summarily tossed out. William Durret Collier and his wife, Mary Meadows Collier, lived up the mountain from Jollett Hollow.

among those summarily tossed out. William Durret Collier and his wife, Mary Meadows Collier, lived up the mountain from Jollett Hollow.

They owned nearly 500 acres of land, harvesting chestnut tanbark each spring and hauling it by horse-driven wagon down the mountains to the tannery in Elkton.

They kept fruit orchards, managed the farm of a wealthier neighbor, and raised six girls and a son.

When the men from Washington came around, they knew they had no option but to sell, and did not protest. They used the money to buy a home at the base of their mountain, outside the future park’s boundaries, close enough that they still walked up to their old orchards to pick apples years after that place was abandoned.

They were happy with what they got, and the stories my family passed down are that most others were happy with what they got too. But maybe that is just my family. After all, this is vastly different from the stories I’ve read about, of Lizzie Jenkins and John Mace and Elmer Hensley and the others who did not want to leave their mountain homes.

Then again, simple satisfaction is nothing we remember in detail, as we do outrage. The blood doesn’t boil, the adrenaline doesn’t rush with something so ordinary as satisfaction.

Then again, simple satisfaction is nothing we remember in detail, as we do outrage. The blood doesn’t boil, the adrenaline doesn’t rush with something so ordinary as satisfaction.

That is nothing we commit to stories, or create mythologies around.

Satisfaction does not bond people together as outrage does. It does not inspire rallying cries that cross generations.

Only outrage and its related emotions do that. And so that is what is remembered. It is why family feuds endure across generations. Why hostilities between two groups can last so long that no one is quite sure why they are hostile anymore, but only that they are.

My ancestors became lost to history, while Lizzie Jenkins and those others became standard bearers for the protesters of government oppression.

Yes, there were authentic tragedies and injustices associated with building the Park. Lives ruined not just when the government threw them from their homes, but decided they were so inferior that they needed to be taken from their families and institutionalized. Lives were wasted, and many literally wasted away in the cold corridors of institutions.

They were victims of the “Progressive Movement” that swept America in the late 1920s and early 1930s, when do-gooders roamed not just the Blue Ridge and Appalachia,  but all through the cities and countryside looking for pockets of poverty to eradicate.

but all through the cities and countryside looking for pockets of poverty to eradicate.

They believed that people of the lowest classes should be either “fixed,” or marginalized, and so set about sorting people into the “deserving” and “undeserving” classes. “Social progress is a higher law than equality,” wrote one reformer.

In Virginia alone, more than 7,000 people were forcibly sterilized. About half of those were deemed mentally ill, the other half mentally “deficient.”

Some women were put away, sterilized, or both because of “loose morals.” Children were taken from their parents because they were “feeble-minded.”

Many of my fellow Blue Ridge descendants have ancestors who were thus locked up for the sin of poverty.

It was a dark time in America. The “fixers” thought they were “doing good.” They were very, very wrong.

We as a nation recognize that people were wronged. We have institutionalized this memory in textbooks and schools. I remember studying the movement and its repercussions in college, and the teaching emphasized the injustice that was done. By remembering, we can hope it will never happen again.

But what we remember must resemble the truth of what really happened, not the hopped-up inaccuracies that continue to fan the flames of anger.

Some descendants are angry that their Blue Ridge ancestors were lied to, told they could stay on in their parkland homes forever.

Yes indeed, this was the plan at one time, to let people stay. There were many early plans that did not come to fruition, and numerous reasons why this one did not happen.

Early on the Park was planned to include nearly 400,000 acres. Because that much acreage would have encompassed too many economically vital farms, and because the Depression was causing contributions from donors to dry up, the planned acreage was drastically reduced to 163,721 acres.

Reduction of the acreage required a new bill from Congress, and a rider was attached promising that current homeowners would be allowed to stay so long as they did not hamper the park.

However, Arno B. Cammerer, a lifelong bureaucrat and future Director of the National Park Service, wrote a report stating, “This particular class of mountain people is as low in the social order and as destitute as it seems possible for humans to get…. It is not known how many squatters of similar degree of intelligence, of lack of intelligence, are within the park area proper, but, every one of them being a potential beggar, it is not considered a practical proposition to authorize their retention on lifetime leases within the park.”

Those are harsh words, and hard to read without feeling anger at their writer for such judgment. He deserves condemnation for making such a report without knowing the people about whom he is writing.

Though a few no doubt would turn to begging, Mr. Commerer accused and convicted the entire mountain populace. It is because of this man’s report and influence that the act of Congress granting lifetime tenancy was discarded, the people forcibly removed. But was the original plan to keep residents in their homes a lie? No. An abhorrent act and reneging of a stated plan, yes. A lie, no.

Some descendants claim, too, that their ancestors were cheated, not given fair value for their homes. I have tried to prove that this is true.

I have searched every document I can find, spent many hours looking for evidence of underpayment. I wanted to find that they were cheated, so as to give justice to the people today who still feel so wronged.

But instead, I found just the opposite. Everything I have seen points to the mountain residents being compensated generously for the enormous disruption to their lives of having to leave their homes.

I found that comparable mountain land sold for an average of $5 per acre before the Park. Indeed, Herbert Hoover bought 164 acres right on the Rapidian River for $5 an acre even as Shenandoah National Park was being planned.

Looking through the National Park Service’s records of payments, it appears that the average compensation was well above that $5 appraised average. My own great grandfather, W. D. Collier, received $4,295 for his 452 acres plus three structures, one a two-story 18′ x 32′ house and another a 14′ x 22′ barn, plus another 13′ x 13′ building.

His per-acre compensation was $9.50 an acre for the forest land that he used to harvest tanbark in the spring. It was not the most valuable land, which would be tableland, but it was productive, income-generating land. He would feel that loss of income and have to seek his livelihood elsewhere.

The median home value in America in 1934 was $2,278, and no doubt far less in the Blue Ridge. But using that figure, Durret Collier would have been able to replace his home and buy approximately 400 acres, about what he lost. Indeed, my great-grandparents bought a house and land, and felt they made out well in the deal.

Did others make out financially as well? Looking at the evidence, I have to say it seems most did.

Did others make out financially as well? Looking at the evidence, I have to say it seems most did.

Fannie Lamb received $3,400 for her 5.9 acres, which must have been prime land. Lloyd Spitler received $200 for his two acres.

John Eppard received $2,074 for his 172 acres. Old Rag United Brethren Church got $1,000 for their quarter acre plus church. The Old Rag school got $800 for their half acre plus schoolhouse.

On the other hand, Allegheny Ore & Iron got only $1.98 an acre for their 1,434 acres, and Bessie Keyser received only $334 for her 102 acres. Most others fell in between those extremes.

It’s easy to see why some might feel their ancestors were cheated when looking at those prices. But it’s helpful to remember that $1,000 in 1934 was the equivalent of $17,763.51 today because of inflation. That is almost a 1,700 percent rise in prices since then, an incredible amount of inflation. I hope this puts some perspective on the prices our ancestors received for their property.

Of course, there is no denying that most mountain people would have far preferred to stay in their homes rather than move off the mountains. Eminent domain is a nasty business, when the state decides that its interests are more important than those of the individual.

Many people believe there is no justification for eminent domain under any circumstances. These are mostly Jeffersonian Republicans who believe the greatest threat to liberty is posed by a tyrannical central government.

That party, the Jeffersonian Republican party, is dead today, but its traditions live on, mostly in the South. For those with that view, the Shenandoah National Park will always seem an illegitimate place, born of the gross injustice served on our ancestors.

For them, only this point is relevant. Many of those ancestors were versed in the Constitution and believed the Park to be unconstitutional. They described it as “federally occupied territory.”

For them, only this point is relevant. Many of those ancestors were versed in the Constitution and believed the Park to be unconstitutional. They described it as “federally occupied territory.”

I am more moderate. I believe that there are occasions when “the greater good” is served by self-sacrifice. And as one who also believes that the most majestic, beautiful, and sacred places in America should be preserved for all generations, I believe that creation of the Shenandoah National Park was an injustice to a few for the greater good of the many.

That my ancestors were made to sacrifice, I am sorry. I can only hope they also saw the greater good of the Park’s creation, and felt justly compensated. In fact, from family stories passed down, I know this to be true. But for the descendants who believe the individual reigns supreme over the state in every or nearly instance, eminent domain is one of the grossest injustices. No other circumstance matters.

This exercise in examining the evidence in development of the Shenandoah National Park was illuminating. I am satisfied in what I found regarding the one big missing piece of information I sought: that mountain residents were indeed compensated fairly.

But I also learned something about those who are still bitter over the park. Only now have I come to appreciate the power of some descendant’s political beliefs in their opinion over whether their ancestors were treated justly. Politics just had not occurred to me, but now it makes complete sense.

The bitterness is not because they think their ancestors did not get fair prices, as I thought. It is not even per se that their ancestors were made to move. It is, instead, that they believe the government has no right to forcibly take an American citizen’s land, no matter how much the compensation.

This is about liberty, and an individual’s rights over the rights and privileges of the government. It was for the ideal of individual rights and liberty that America was founded, and they believe no government has the right to infringe on those rights. Eminent domain is one of the most egregious usurpations of rights.

It is true that the depiction of mountain residents was unnecessarily pejorative, and it was unfortunate that many were swept up in the national movement for social engineering.

It is a pity that the plan to allow residents to stay for their lifetimes was undermined by one man. These are all important elements of the mishandling of the Park’s development process.

Would it go more smoothly if done today? It’s hard to say. Government is messy. Two-party democracy is especially messy. (Winston Churchill once said, “democracy is the worst form of government except for all those other forms that have been tried.”)

I cannot say that all of the mistreatment can be attributed to the ways of that time in history, though I believe that the slanderous accusations and social engineering experiments were of that time in history and would not be repeated today.

America has the greatest system of national parks in the world. Writer Wallace Stegner called them “America’s best idea.” I may not go that far, but I am proud of them and thankful for them.

As our country gets more and more crowded, there will be a time in the not so distant future when these will be our only places of pristine wilderness, which we all need for the health of our bodies and souls. For me, that is the greater good that made Shenandoah National Park necessary to create.

One only has to visit those peaks and woods during October to see why they were worth preserving. To walk among the tall trees and thick underbrush, through sun-warmed meadows and along cascading streams, stirring up that musty forest floor scent with every step, moving through rays of autumn light that slant through the bent and crooked branches.

This is a quiet beauty. Even the flaming autumn colors blend to a muted tapestry that folds over those soft-rolling and time-worn mountains. I hear echos of my ancestors deep in those woods, their voices riding on the wind like phantoms of the past.

Four generations of my families lived and died there, names like Markey, Meadows, McDaniel, Collier, Tanner, and Breeden still today rising up from hallowed Blue Ridge ground on grave markers that remained behind when the living left.

Today the Blue Ridge belongs to all of us. And for that I am grateful.

left Brooklyn.

left Brooklyn. you heard me tell the story and then remembered it as though it was your own.”

you heard me tell the story and then remembered it as though it was your own.”

So some descendants have taken action, working with the Park to ensure that our ancestors’ histories are told to Park visitors, and told in the right light; building memorials outside the Park, maintaining Park-land cemeteries.

So some descendants have taken action, working with the Park to ensure that our ancestors’ histories are told to Park visitors, and told in the right light; building memorials outside the Park, maintaining Park-land cemeteries.

ancestors, and we can almost see ourselves right there beside them, conversing in their ancient language, living between our time and theirs.

ancestors, and we can almost see ourselves right there beside them, conversing in their ancient language, living between our time and theirs. bulldozed to make way for urban cities, the old people moved carelessly to apartment dwelling or some other unfamiliar government convenience.

bulldozed to make way for urban cities, the old people moved carelessly to apartment dwelling or some other unfamiliar government convenience.

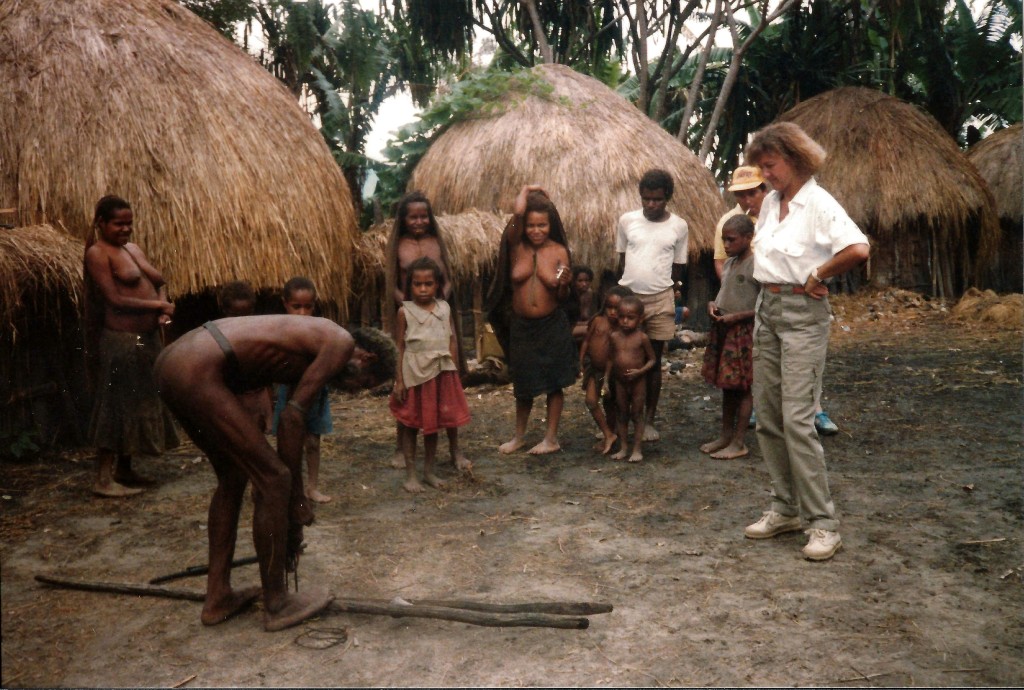

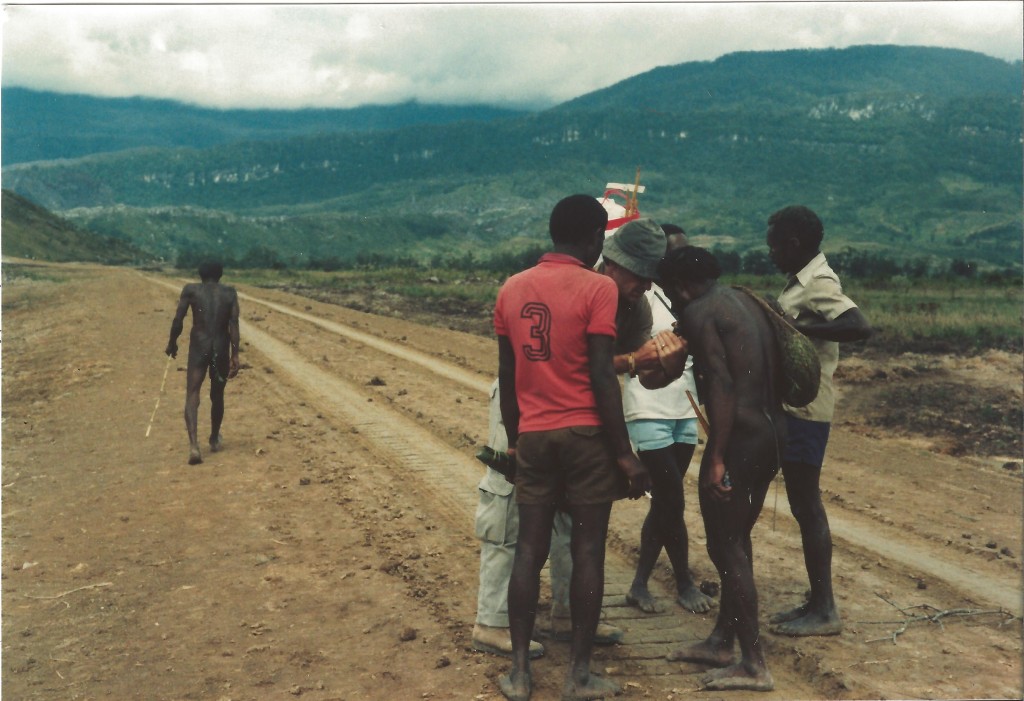

Michael Rockefeller, of “those” Rockefellers, was part of that team until he disappeared, his body never to be found.

Michael Rockefeller, of “those” Rockefellers, was part of that team until he disappeared, his body never to be found.

a distant island, decided to build a road over the mountains and into the Baliem Valley, where the primitive Dani lived.

a distant island, decided to build a road over the mountains and into the Baliem Valley, where the primitive Dani lived. nslaught of popular culture? No. I can say that unequivocally. It may not be tomorrow, or next year, or in ten years, but it will happen.

nslaught of popular culture? No. I can say that unequivocally. It may not be tomorrow, or next year, or in ten years, but it will happen.

sprung from between their fallen walls, and 80 seasons of fallen leaves have covered their remnants.

sprung from between their fallen walls, and 80 seasons of fallen leaves have covered their remnants.

But for the tenants, I’m not so sure. I lived many years in rentals before buying a home. Renters have few rights, no matter where you are. That’s simply the way it is, dehumanizing as it may be.

But for the tenants, I’m not so sure. I lived many years in rentals before buying a home. Renters have few rights, no matter where you are. That’s simply the way it is, dehumanizing as it may be.

I imagine their very first reaction was negative though, on hearing that the government was condemning their property and evicting them from their homes. Who would be happy about that? But time, and the offer of money, which was in short supply for most of these people, won in the end.

I imagine their very first reaction was negative though, on hearing that the government was condemning their property and evicting them from their homes. Who would be happy about that? But time, and the offer of money, which was in short supply for most of these people, won in the end.

These were families who had been there for generations. Many lived in compounds of extended families, with parents, brothers, grandparents all with their own small homes. Some were so poor that they couldn’t afford to move anywhere else. Each family’s circumstance was different, but I guess that every one of them was a complex tangle of emotions, needs, desires, and problems that had to be dealt with before they could pull up roots and leave.

These were families who had been there for generations. Many lived in compounds of extended families, with parents, brothers, grandparents all with their own small homes. Some were so poor that they couldn’t afford to move anywhere else. Each family’s circumstance was different, but I guess that every one of them was a complex tangle of emotions, needs, desires, and problems that had to be dealt with before they could pull up roots and leave.

casting long shadows from its woodlands, that endless green like a carpet of rumpled velvet, and those blue-tinged mountains beyond, brings a tear to my eye for such beauty.

casting long shadows from its woodlands, that endless green like a carpet of rumpled velvet, and those blue-tinged mountains beyond, brings a tear to my eye for such beauty.

Mary Meadows, daughter of Mitchell Meadows and great great granddaughter of Francis Meadows, was born in 1864 in the Blue Ridge, just up from Jollett Hollow, which sits on the eastern edge of the great Valley of Virginia, the Shenandoah. There she grew up, and there she married William Durrett Collier, whose people also came to the mountains early.

Mary Meadows, daughter of Mitchell Meadows and great great granddaughter of Francis Meadows, was born in 1864 in the Blue Ridge, just up from Jollett Hollow, which sits on the eastern edge of the great Valley of Virginia, the Shenandoah. There she grew up, and there she married William Durrett Collier, whose people also came to the mountains early.

days like their parents and their grandparents and really, like you and me, a version of the American life, if not the American dream. They raised five girls and a boy, all hard-working but fun-loving youngsters who, my mother quotes her mother, Durrett and Mary’s youngest, as saying, “hoed corn all day and danced all night.”

days like their parents and their grandparents and really, like you and me, a version of the American life, if not the American dream. They raised five girls and a boy, all hard-working but fun-loving youngsters who, my mother quotes her mother, Durrett and Mary’s youngest, as saying, “hoed corn all day and danced all night.”