Snow came the night we reached Shenandoah in late December of 1968 after driving night and day from Southern California to make it while there was still time.

It lay shining on the fields in the light of a full moon, glistening on the trees, and falling softly before the headlights, whipped into small furies by the air displaced as we passed.

It lay shining on the fields in the light of a full moon, glistening on the trees, and falling softly before the headlights, whipped into small furies by the air displaced as we passed.

Uncle Charles and Aunt Ola were as excited as children that the first good snow arrived to greet us. Good luck, they said. It was late, nearly midnight when we arrived. My little sister Ellen was asleep in the back seat, sprawled out like a cat, limbs akimbo and face hidden in a bramble of long hair.

My father picked her up. Half awake, she put her arms around him and he carried her up the steps and across the wood slat porch. At the front door Uncle Charles reached out and took her into his own arms. She woke and hugged him tight while he cried, burying his face in her hair.

Ma lay in a hospital bed that dominated the living room from the middle like a hub, furniture pushed back to the walls and facing the bed as though on spokes. Her tiny body was shrouded by a thin white sheet and protected, in case she rolled over, by high rails on the bed’s sides. She hadn’t rolled over. She hadn’t even moved a finger.

Uncle Charles, my mother’s brother, had the ancient wood stove stoked up and pouring out heat so stifling that I could hardly breathe. Aunt Ola, mother’s sister, was general of the operation. She fussed over us, took our coats and pointed us to seats, all in the name of love, both of us and of order.

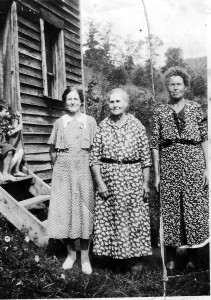

My mother had stood back until then, letting her siblings huddle around us first, embracing each of us in turn to erase the years of absence that had stood between us. That is her nature, to quietly observe and to talk only when there is something worth saying. Now she came to us, arms outstretched and smile wide.  She had flown back several months before to be with her mother, the two of them caring for each other, the elderly mother and the daughter who had been recently ill. They had those few wonderful months together, taking walks as far as Naked Creek, sharing quiet meals, working side-by-side in the garden, before Ma had her stroke.

She had flown back several months before to be with her mother, the two of them caring for each other, the elderly mother and the daughter who had been recently ill. They had those few wonderful months together, taking walks as far as Naked Creek, sharing quiet meals, working side-by-side in the garden, before Ma had her stroke.

I don’t know if Ma knew we were there or not. She had the stroke a week before our arrival, had held out till then, but just couldn’t hold it off those final few days until we arrived. The stroke took her from us and put her in a coma. I gazed at her smooth face, pale and lineless, her white hair swept back and tucked behind her head.

She had worn a sun bonnet all her life, one of those pioneer woman types with full gathered cap, massive quilted brim, and short “skirt” in the back, all held on by a wide bow tied under her chin. That and a sun parasol kept her skin like a girl’s her whole life. She was so still now that I could not detect even her breathing. I leaned in and kissed her cheek. Uncle Charles put his hand on my arm; I turned and his thin arms encircled me next. We were not yet done with the greetings.

That night I slept above the living room, right about where I imagined my mother’s childhood bed had sat. The heat up there was just as unbearable as below, and I opened the window, pulling my light bed as close as I could to the cool air outside. Ellen and I watched a gentle snow fall, the fields sparkling in the moonlight. I breathed in the crisp night, so unlike the salt and dust I could taste in the air at home, near the Pacific Ocean in Southern California.

Sometime during the night lightning struck a nearby tree with a deafening roar. I bolted awake, my hair standing on end, the room shimmering with electricity. Ellen and I looked at each other with wide eyes. “Wow!,” we both said, California style, and crept to the window for some lightening gazing. There’s nothing like that in Southern California, and it was as good as a Disneyland ride.

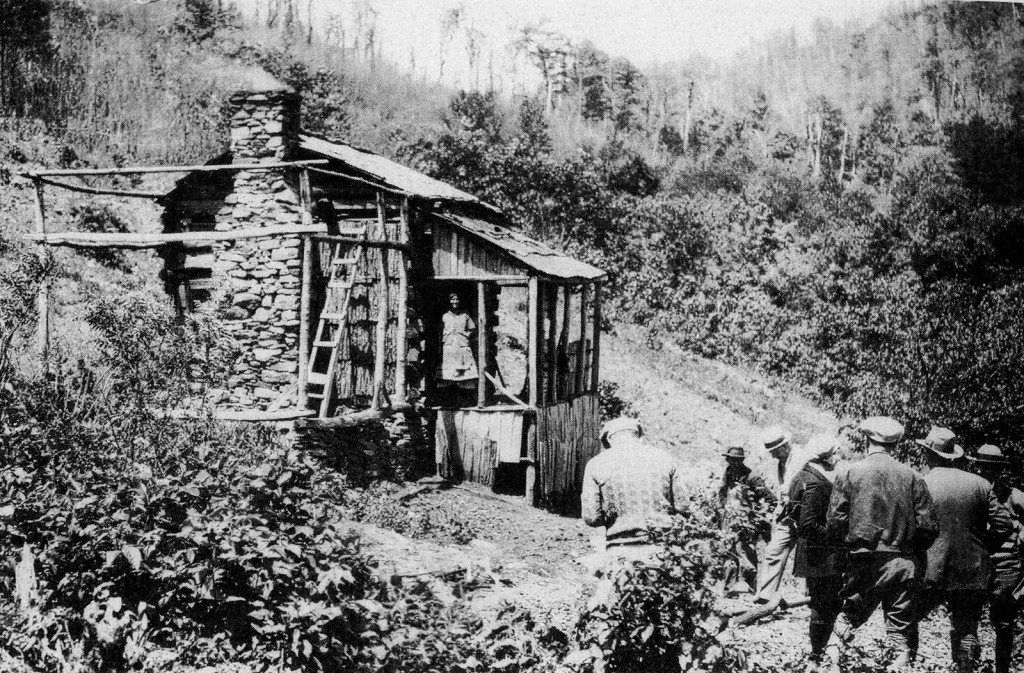

The next day we explored the farm, my father, sister and I. We sifted through the old barn, gathering up the scythe and sickle, hay fork and cross-saw; examined the old worn wood, found a large draft horse harness with fat leather collar. In the house we marveled at the wood stove my grandmother still cooked on in 1969, and the flat iron she still heated on the stove to iron clothes.  Not to mention the well-worn water pump that sat just outside the kitchen door, the outhouse just beyond the garden, the bedpans and washing basins that were still a part of daily life there.

Not to mention the well-worn water pump that sat just outside the kitchen door, the outhouse just beyond the garden, the bedpans and washing basins that were still a part of daily life there.

My grandmother was never lured by the modern, never longed for the newest model washing machine or toaster. The only time I ever heard she wanted anything at all was after the first ride she took in an automobile. It belonged to Shenandoah’s physician, Dr. Shuler, who offered her a ride home from town one day. She came into the house grinning widely and said, “I’m going to get us one of those.”

Uncle Charles and Aunt Tessie, his wife, lived next door. Tessie loaned me magazines to read that winter, but my mother made me take them back when she saw that they were Hollywood gossip rags, Confidential, Screenland, Uncensored. I had never seen anything like them, much racier than the fan magazines you see today, full of lust and murder. Charles and Tessie lived in one of those upright old Virginia country houses whose only luxury was electricity, but theirs was furnished with the most salacious reading material of the day. The irony was not lost on me.

We settled into my grandmother’s house, my mother cooking on the wood stove, my father tidying up the farm, reading his newspapers and mumbling about the Vietnam War. He was a proud American and patriotic World War II vet, but was wholly outraged by this war. “Sending those boys to their deaths, and for what?”

Every day there were visitors, either neighbors bringing homey casseroles or family members coming to visit us and pay their respects to Ma. I loved every minute of it, wished we had kindly neighbors in California, wished we had more family there.

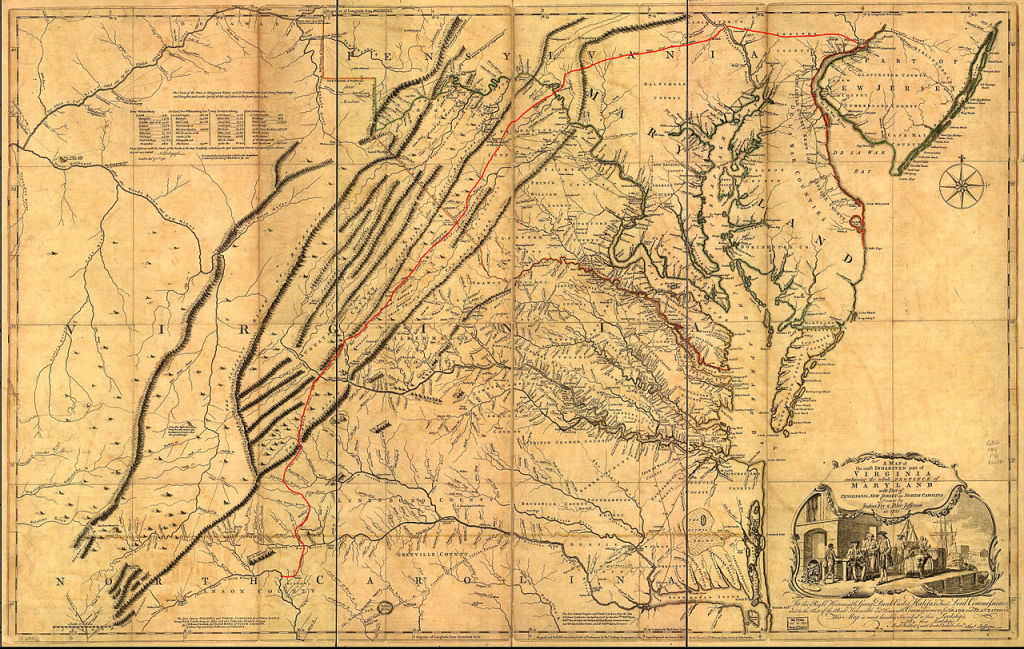

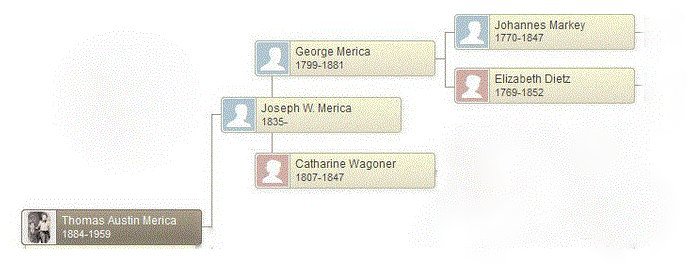

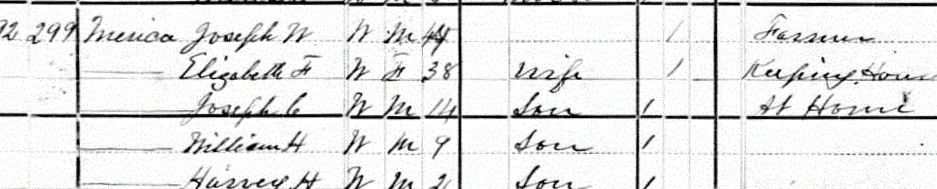

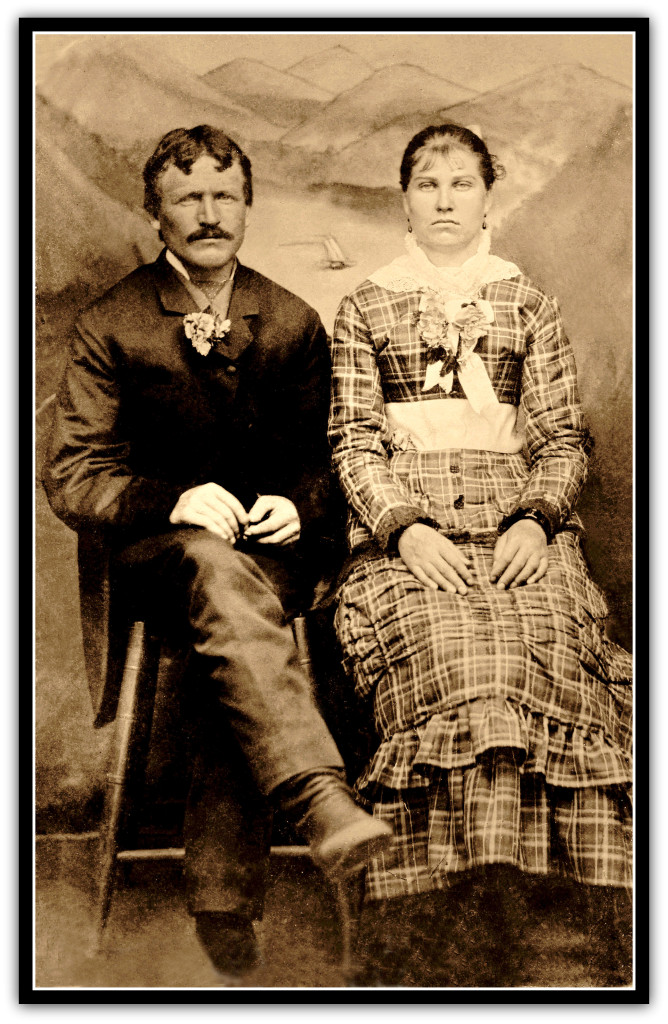

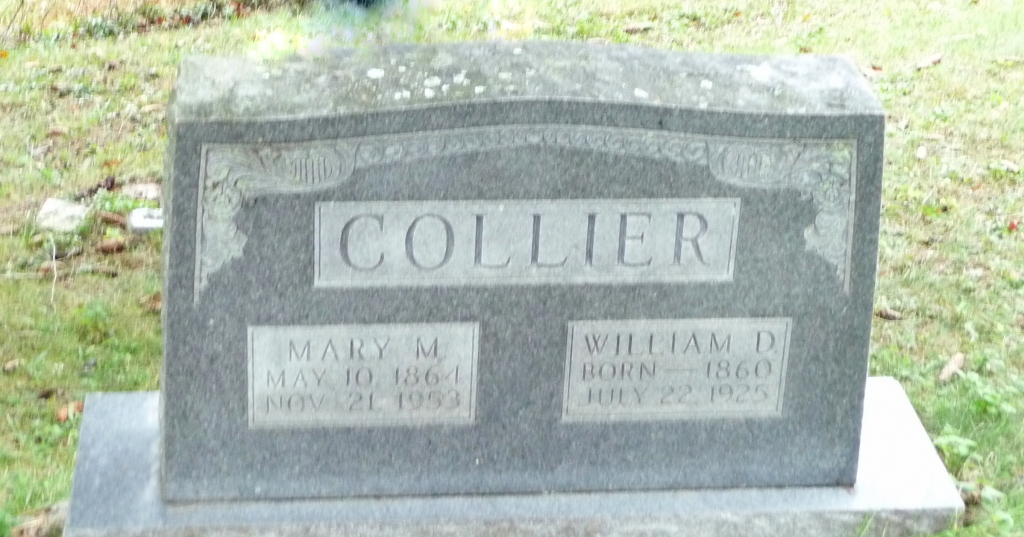

Ma and Pop, my grandparents, Florence and Tom Merica, were worried when their fourth daughter announced she was moving with her husband and baby to California. People didn’t leave Shenandoah, or not many did. Ma was especially worried. She and Ruth, my mother, had a special relationship. More than her other daughters, Ruth loved spending time with her mother, helping her in the kitchen or garden, going along when Ma went “a’visitin’.” Ma knew it would be many years before she saw her daughter again, and I know she grieved. Sure, we visited now and then. But not enough.

Now here we were and Ma didn’t even know. Or if she did, she could not communicate it. Occasionally I crept near and sat by her side, holding her hand. I was too self-conscious to talk to her, as Uncle Charles did, and did not feel intimate enough to stroke her hair and cheek, as my mother did.

I simply sat, awkwardly, until a closeness overcame me, a love for my grandmother who I barely knew, a longing for her to wake and turn to me with arms open to envelop me, making up for all those years away from her. After sitting with these feelings for a while, I could get up again and move on.

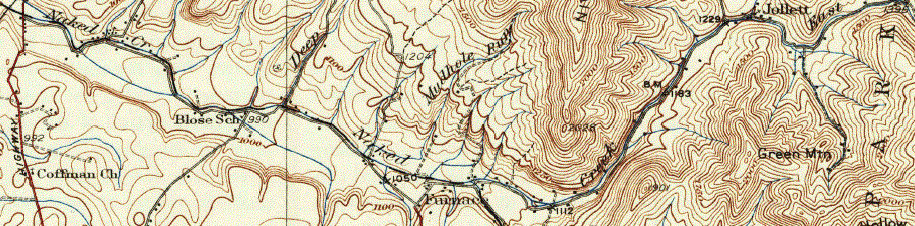

Ma’s brother, my Great Uncle Charlie, had a farm up at Number Two Furnace, just up the rise from Jollett Hollow. We drove over to his place one snowy afternoon to cut a nice Christmas tree, and were all delighted when he pulled out a full-sized sleigh and harnessed the big old work horse to it. A real sleigh, just like Santa had, even with bells around the horse’s collar. So there we went, dashing through the snow in our one-horse open sleigh, into the woods to find the perfect tree. Not Douglas fir, like we always got at home, but cedar, the traditional Christmas tree of Virginia.

The next few days were busy, what with Christmas around the corner. We shopped in Harrisonburg, and I spent a few days with my uncle Jesse’s family in Waynesboro. My Aunt Emily and I sat at her kitchen table and talked. I told her about the piglets at Great Uncle Charlie’s farm and she told me she would love to  have a lap pig, “They’re so cute. And smart.”

have a lap pig, “They’re so cute. And smart.”

We went shopping and she gave me $5 to buy anything I wanted. I chose a yellow dress for Ellen. One afternoon, sitting in the kitchen, their son Tom came in with a friend. He looked to be a few years older than my 16. After introductions Tom nodded silently to me, then he and his friend disappeared into the back. “Well!,” I thought, “I came a long way to be here, I deserve better than that!” Years later we would be close friends.

When I returned my grandmother was yet there, quiet and still, breathing steadily, her face peaceful. My mother, Uncle Charles, and Aunt Ola took turns sitting by her side so Ma was never alone, though none knew if she was aware of the doting children who sat vigil. My mother took the evenings, pulling in a small bed to sleep beside her. That evening we gathered after dinner in the living room. Uncle Charles walked home, which was next door, just across the field. He stoked the fire again before leaving, as always.

Ola was gone, it was just the five of us. I pushed my chair near the thin-paned window to draw some of its chill, trying to offset the blasting heat. My father was on the couch reading a newspaper, my little sister on the floor playing. I looked up from my book and saw my mother standing over Ma’s bed, stroking her hair with tenderness.

She spent her adult life in California, arriving with my father and their first baby, then a toddler, just after the end of World War II. We did not travel back to see her Shenandoah family as often as we would have liked. There were four children to raise, and cross-country travel was far more difficult then. My grandmother never learned to read or write, so intimate letters between the two were impossible. As for the phone, I don’t know why they did not talk more often, except that both tended to quietness.

She spent her adult life in California, arriving with my father and their first baby, then a toddler, just after the end of World War II. We did not travel back to see her Shenandoah family as often as we would have liked. There were four children to raise, and cross-country travel was far more difficult then. My grandmother never learned to read or write, so intimate letters between the two were impossible. As for the phone, I don’t know why they did not talk more often, except that both tended to quietness.

And now my mother was like an angel at my grandmother’s bedside, her face as serene as Ma’s, radiating something so essential and chaste that it felt like an essence distilled to its truest form, that bond between child and mother, or spirit and body. Her hand lightly caressed Ma’s brow, slowly stroking her fine white hair back and to the side. It was the most simple expression of pure love I had ever seen, and I could not take my eyes from her. The room was quiet, only the occasional snap of sparks in the fire or rustle of paper.  Ma was as small as a girl, her form beneath the sheet barely more than a bas relief in cloth against the bed.

Ma was as small as a girl, her form beneath the sheet barely more than a bas relief in cloth against the bed.

Mother brushed back a strand of Ma’s hair, tucking it behind her ear. She touched her brow, ran the back of her hand across her cheek. Then, her soft words, “She’s gone.” At that moment I had never loved my mother more.

gypsy marauders who sneaked by night would not see their house.

gypsy marauders who sneaked by night would not see their house.

ur hotel suite had a beautiful view of the Roman Coliseum on one side, and around the corner on the other was the spectacular Basilica di Santa Maria Maggiore. We decided to start our day there.

ur hotel suite had a beautiful view of the Roman Coliseum on one side, and around the corner on the other was the spectacular Basilica di Santa Maria Maggiore. We decided to start our day there. Scanning the street, I spied one of Italy’s tiny police cars rounding the church, and flagged it down. What ensued was a mad-cap ride through the streets of Rome in the back of a police car, with countless other police cars joining the chase, each going a different way. It was comical in a Buster Keaton, Keystone Cops way.

Scanning the street, I spied one of Italy’s tiny police cars rounding the church, and flagged it down. What ensued was a mad-cap ride through the streets of Rome in the back of a police car, with countless other police cars joining the chase, each going a different way. It was comical in a Buster Keaton, Keystone Cops way. Once we found out more about these maligned people we felt compassion for their lifetime of misfortune. We decided we did not want to press charges, but by that time it was too late. The state had taken control. We didn’t even have to testify for those two women to be convicted, and for their children to be put in homes, though family members would be able to extract the children. The sentence was one year. We felt horrible. My husband kept track of the sentence, and on the anniversary of their release we hoped and prayed for their better lives.

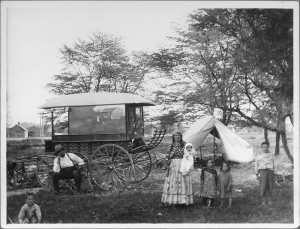

Once we found out more about these maligned people we felt compassion for their lifetime of misfortune. We decided we did not want to press charges, but by that time it was too late. The state had taken control. We didn’t even have to testify for those two women to be convicted, and for their children to be put in homes, though family members would be able to extract the children. The sentence was one year. We felt horrible. My husband kept track of the sentence, and on the anniversary of their release we hoped and prayed for their better lives. They came to America originally in the 17th and 18th centuries, banned as they were from England, France, Portugal and Spain. More arrived from Serbia, Russia, and Austria-Hungary after the 1880s.

They came to America originally in the 17th and 18th centuries, banned as they were from England, France, Portugal and Spain. More arrived from Serbia, Russia, and Austria-Hungary after the 1880s.

The Gypsy’s ways have always been misaligned with the cultures around them.

The Gypsy’s ways have always been misaligned with the cultures around them.

bulldozed to make way for urban cities, the old people moved carelessly to apartment dwelling or some other unfamiliar government convenience.

bulldozed to make way for urban cities, the old people moved carelessly to apartment dwelling or some other unfamiliar government convenience.

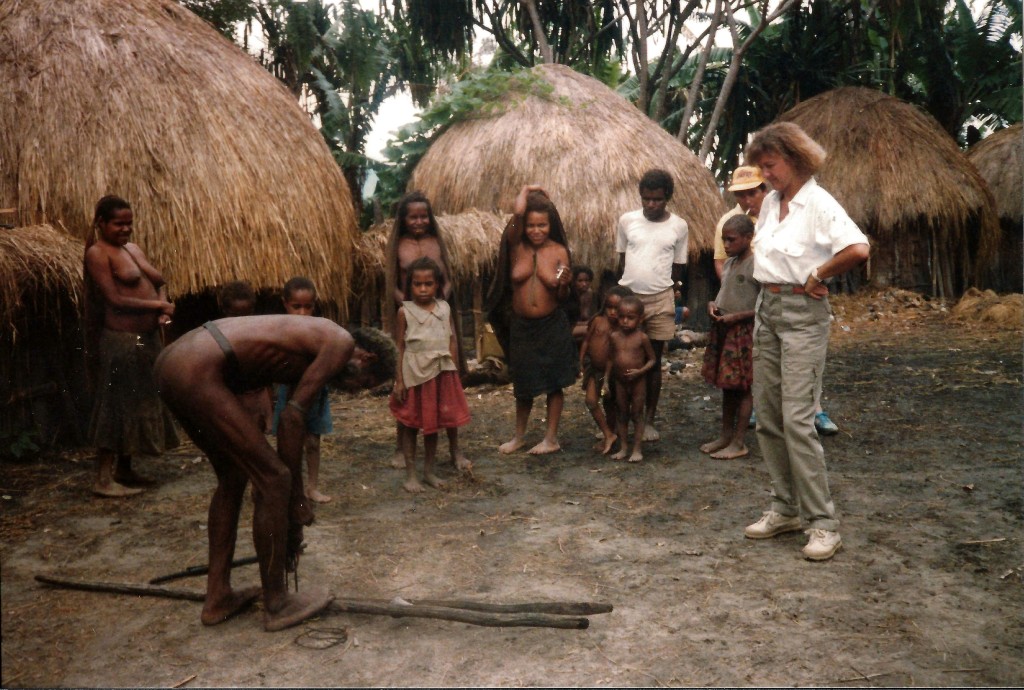

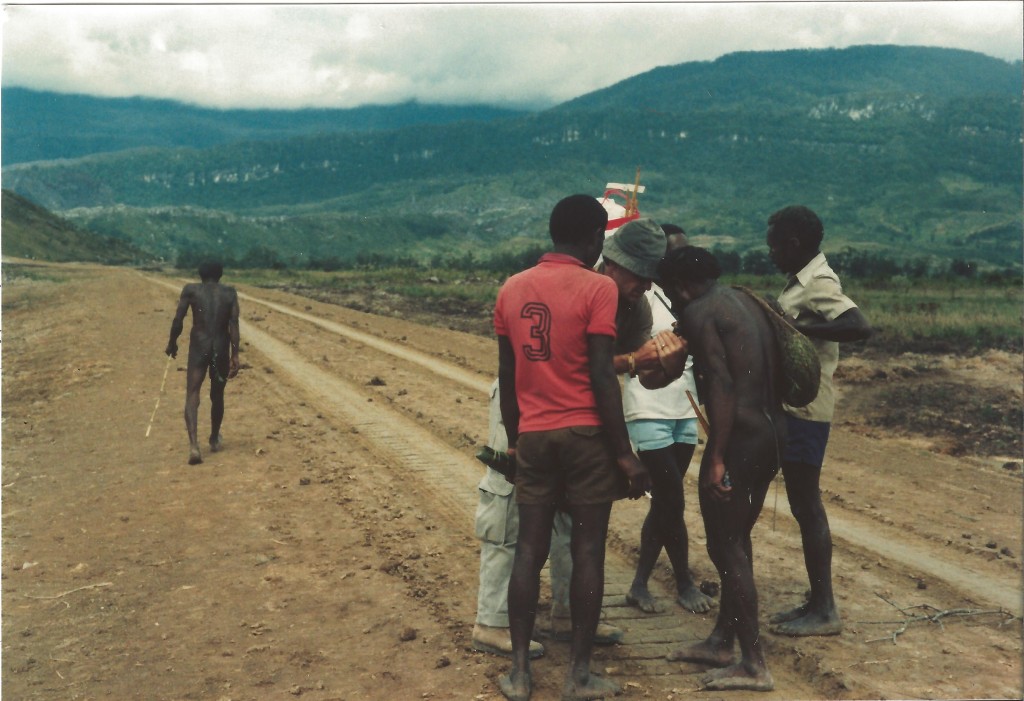

Michael Rockefeller, of “those” Rockefellers, was part of that team until he disappeared, his body never to be found.

Michael Rockefeller, of “those” Rockefellers, was part of that team until he disappeared, his body never to be found.

a distant island, decided to build a road over the mountains and into the Baliem Valley, where the primitive Dani lived.

a distant island, decided to build a road over the mountains and into the Baliem Valley, where the primitive Dani lived. nslaught of popular culture? No. I can say that unequivocally. It may not be tomorrow, or next year, or in ten years, but it will happen.

nslaught of popular culture? No. I can say that unequivocally. It may not be tomorrow, or next year, or in ten years, but it will happen.

sprung from between their fallen walls, and 80 seasons of fallen leaves have covered their remnants.

sprung from between their fallen walls, and 80 seasons of fallen leaves have covered their remnants.

But for the tenants, I’m not so sure. I lived many years in rentals before buying a home. Renters have few rights, no matter where you are. That’s simply the way it is, dehumanizing as it may be.

But for the tenants, I’m not so sure. I lived many years in rentals before buying a home. Renters have few rights, no matter where you are. That’s simply the way it is, dehumanizing as it may be.