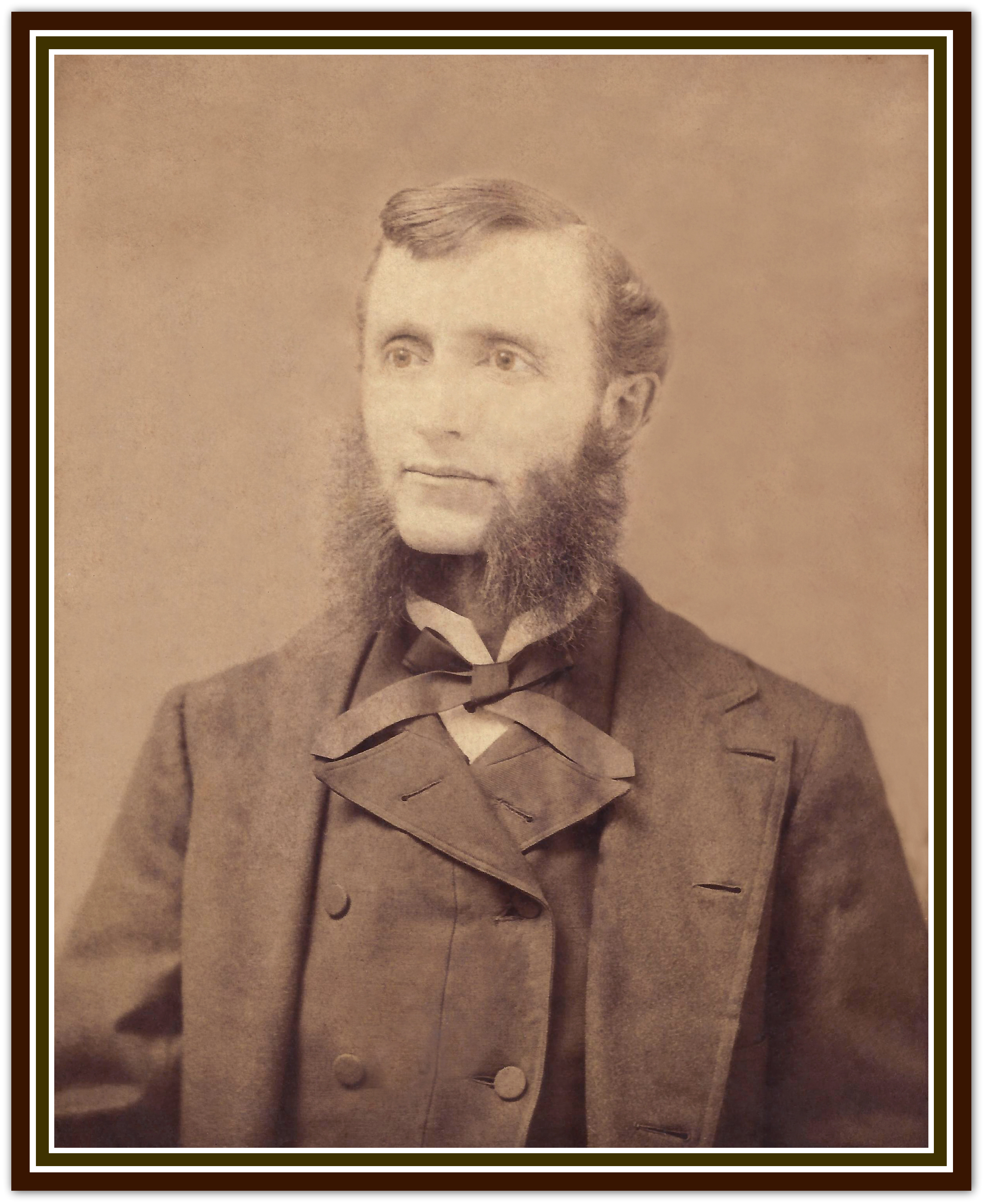

F.O.E. CHAPTER 1: I never met my great-grandfather, Francis Otto Eggleston, a distinguished-looking gentleman with enormous, liquid eyes who, even at 89, stood as straight as the ladder-back chair of his that I inherited.

His nose was prominent, but matched the proportion of his eyes and mouth, and was balanced by noticeably high cheekbones.

I do not see any similarities between us, though I feel them mightily.

As a toddler he was “a chubby little chap in a pinkish dress, with a belt,” and as a young boy wore boots, “with red tops and copper toes.” Which may explain his penchant for always dressing well.

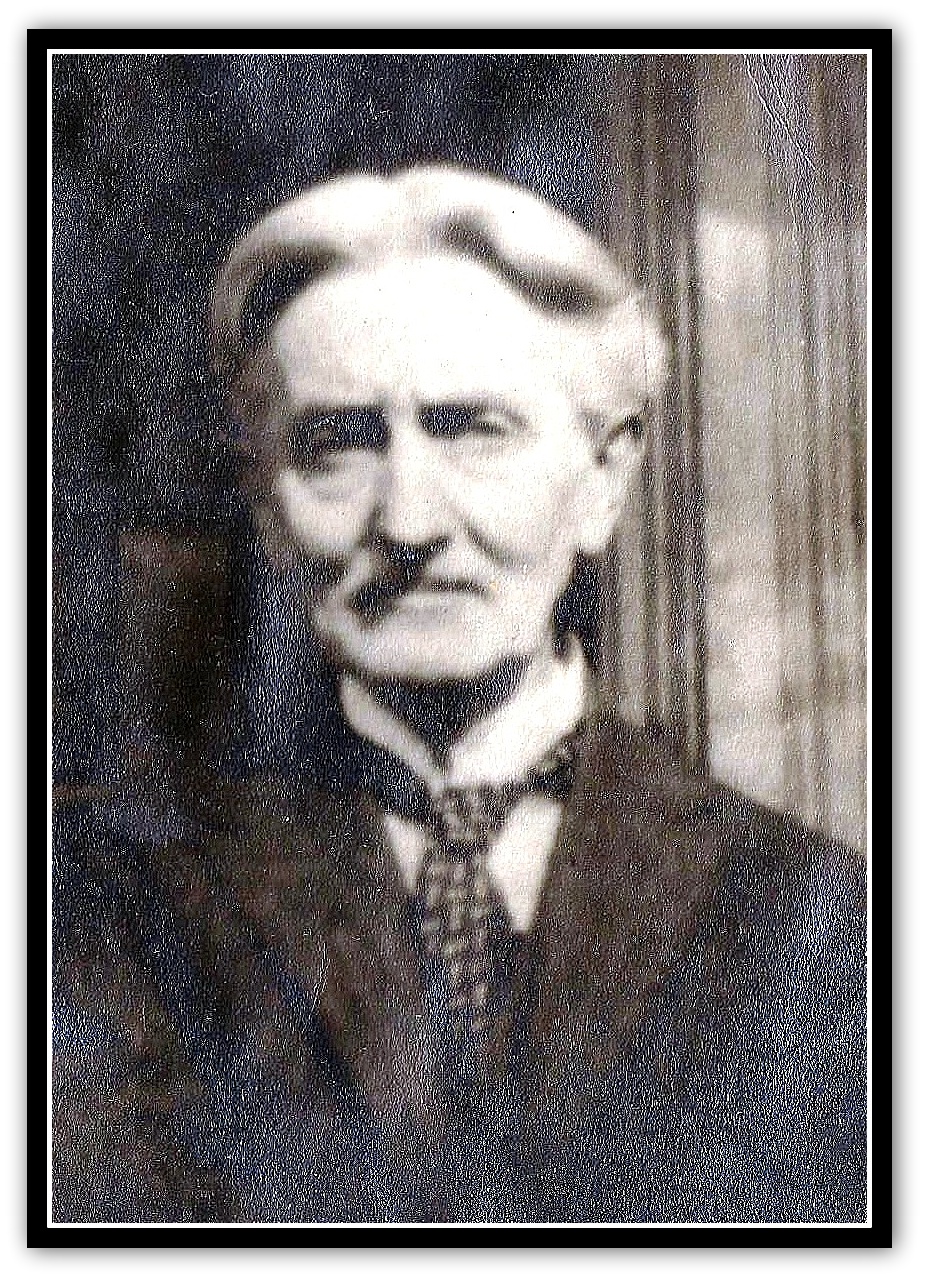

When grown he wore a white shirt and tie nearly every day of his life, usually with a suit, often three-piece, or at least with jacket.

As a young man, he sported mutton-chop sideburns so large that they nearly met and merged on his chin, just above a ribbon bow tie and well-starched high-collar shirt.

As a young man, he sported mutton-chop sideburns so large that they nearly met and merged on his chin, just above a ribbon bow tie and well-starched high-collar shirt.

His hair must have been wavy, because in photos it is barely tamed across his forehead and combed as well as he could back from his ears.

By old age he had let his cotton-white hair grow longish, and swept it back from his forehead, where it fell to either side in a distinguished mane.

The family called him Grandfather, a testament to his dignity, and the formality of their time and place in history.

As for his character, Grandfather was gentle, a romantic and a dreamer.

How do I know?

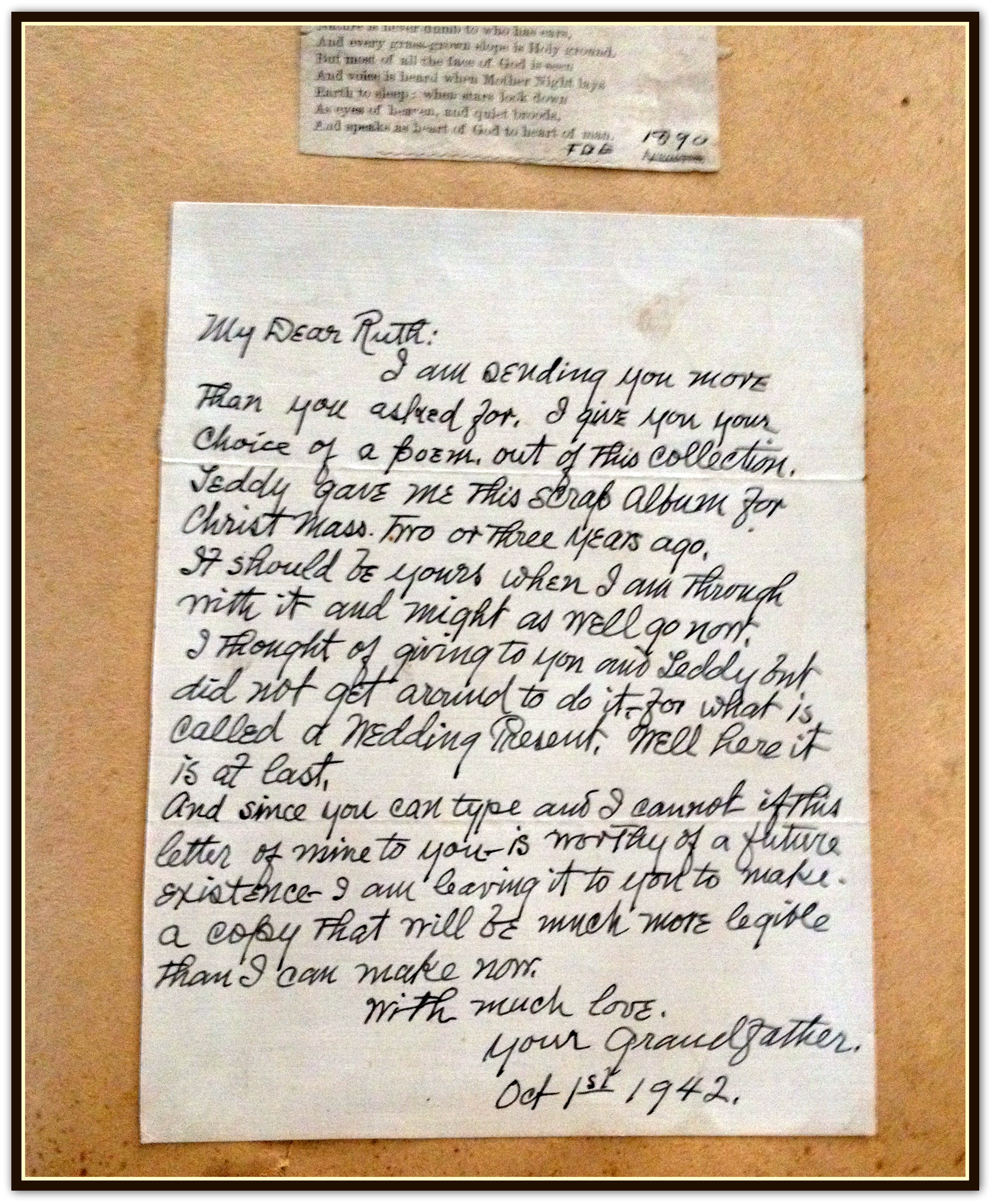

Because he left his letters, poetry, lectures, and other writings, including a twenty to thirty thousand word biography, to my mother, his beloved granddaughter-in-law, and so I know him as well as his words can express.

“I know that I was a poetic and romantic boy with a good bit of natural piety but little religion of the standard type. I have the same peculiarity after 80 years,” he wrote in his biography.

Fortunately, Grandfather’s was not a family that discouraged dreaming or education, and both he and his brother, DeWitt, were given ample room for study, including being sent to the best schools available.

When he was a child, Cleveland, 25 miles distant from the Eggleston farm, was no more than “a largish village,” as he described.

His mother died young of typhoid fever, as did his sister, Mary. I wrote about the epidemic that befell their home previously, here. Such tragedy was, unfortunately, not uncommon.

Francis was expected to perform the duties of a typical 1860s farm boy, helping around the farmyard, in the fields, and with the livestock, and he did so, but not with enthusiasm. “I was not by size or weight a country man, as my own weight was only about 120 pounds.”

His lack of enthusiasm caused others to think him lazy, but “the true fact was that I was always averse to farm drudgery and dirt. I was mechanical, and always had something to make or repair – lazy I was not.”

Still, he found other aspects of farm life idyllic.

“My brother and I were beauty-haunted, and lived in our own world until he went away to school in his early adolescence.”

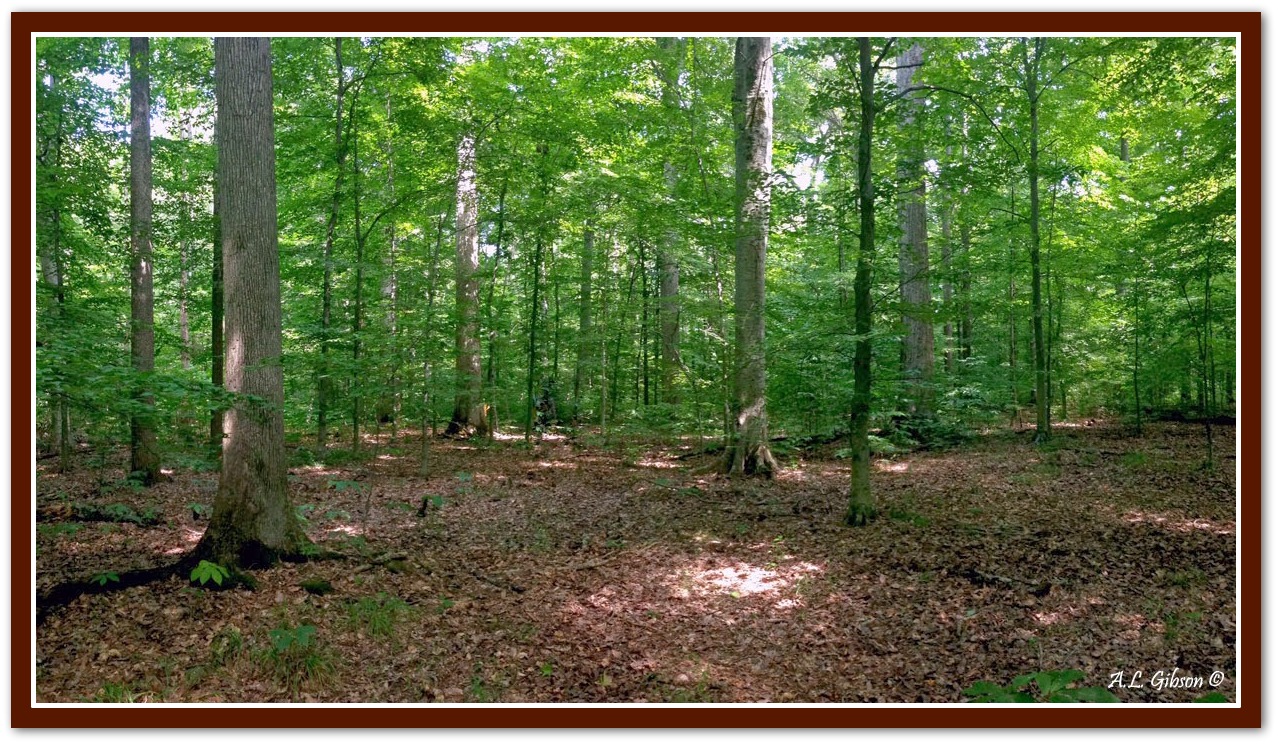

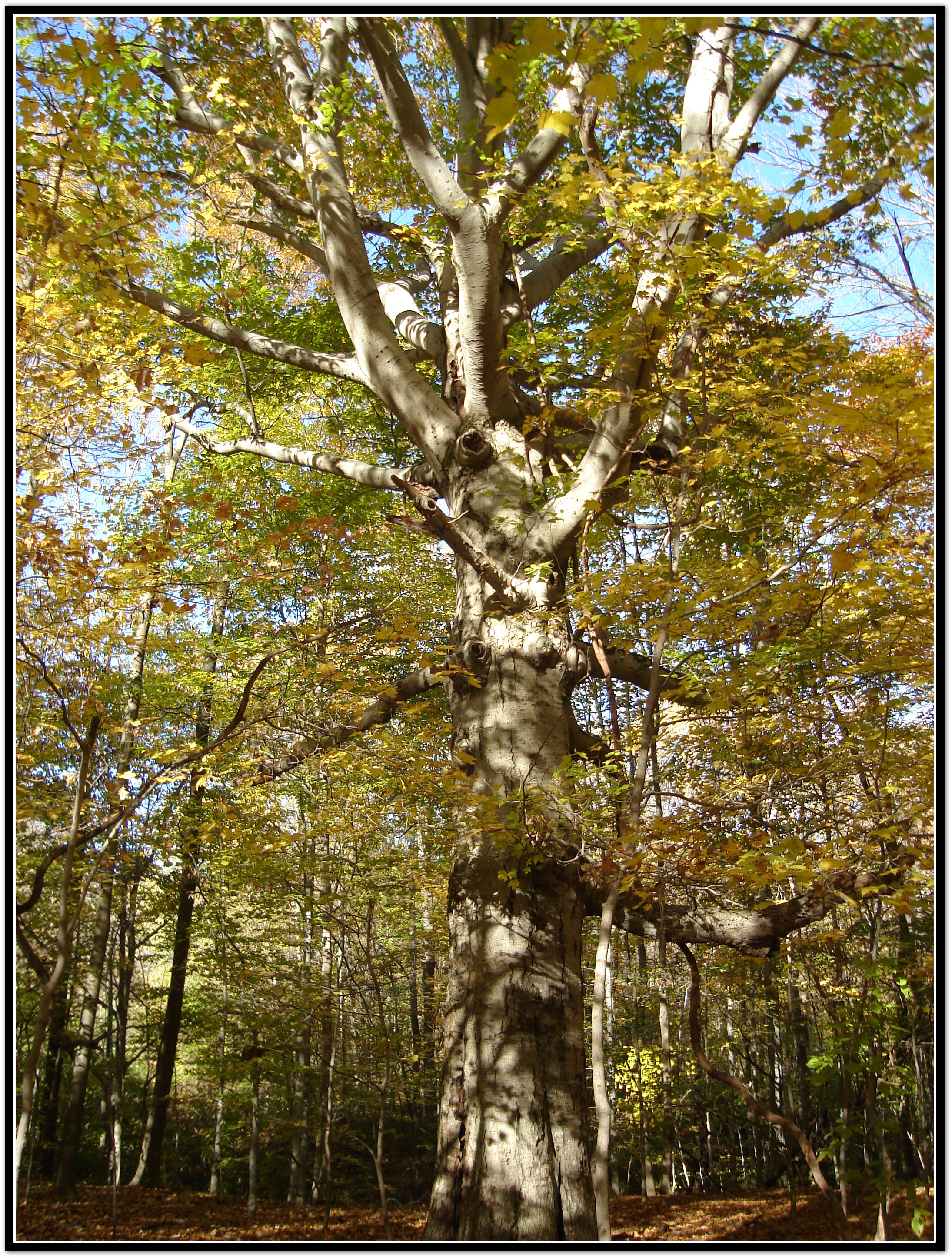

There was a woods behind the farm’s barn, and Francis considered it the loveliest part of their large property.

Just seeing photos from that area of the country, I can see why he loved those woods. I’m from Southern California, where a mention of “woods” brings to mind golf clubs, and anything that’s “woody” might be just an old surf jalopy.

Grandfather’s woods were untouched by saw or road. The trees were so healthy that they practically fluoresced green in springtime, their shoots of bright new leaves tittering in the slightest breeze like tiny dancing elves.

There were no chestnut trees, but they had hickory trees so big around that a full-grown man could not wrap his arms around them.

There were no chestnut trees, but they had hickory trees so big around that a full-grown man could not wrap his arms around them.

And beech trees that towered to 80 or 100 feet, their root base emerging from the ground as if the tree was being ripped from the dirt in its need to grow higher still.

In fall the canopy opened and light dappled the still-crimson and gold leaf carpet below to give a hint of warmth to a wanderer.

And in winter, snow hid any path but crunched underfoot, ensuring a dreamer could find his way back as long as he was mindful of weather.

The dreamer and poet in Grandfather emerged early. Every moment he could steal away, he read and memorized poetry.

The biography he wrote in later years overflows with references to classic writers and quotes from poems both famous and obscure.

The biography he wrote in later years overflows with references to classic writers and quotes from poems both famous and obscure.

I imagine him retreating to those woods with his books, especially Emerson, to whom he was ever devoted.

Francis and DeWitt enjoyed getting out of the farmyard, where Grandfather could indulge his poetic side.

His biography notes that they, “acted the part of shepherds in spring, and in season there were raspberries to pick, and blackberries. Then there were apples to gather, and pears and cider apples – plus cider.”

Grandfather felt he didn’t fit on the farm. Yet he learned duty and discipline, tempering his “poetic and romantic” soul.

His was the best of worlds. His mind wandered free, yet he was not a free spirit. This is a description you’ll see me use often for Grandfather.

In his biography, he quoted John Greenleaf Whittier:

Life made by duty epical

and rhythmic with the truth.

Beauty and wisdom where his loftiest goals. Duty and service were his calling.

This will become clear in the rest of Francis Eggleston’s story, which you can find in Chapter 2, here.

Pingback: A (Reluctant) Farm Boy’s Life in 1865 | We're All Relative