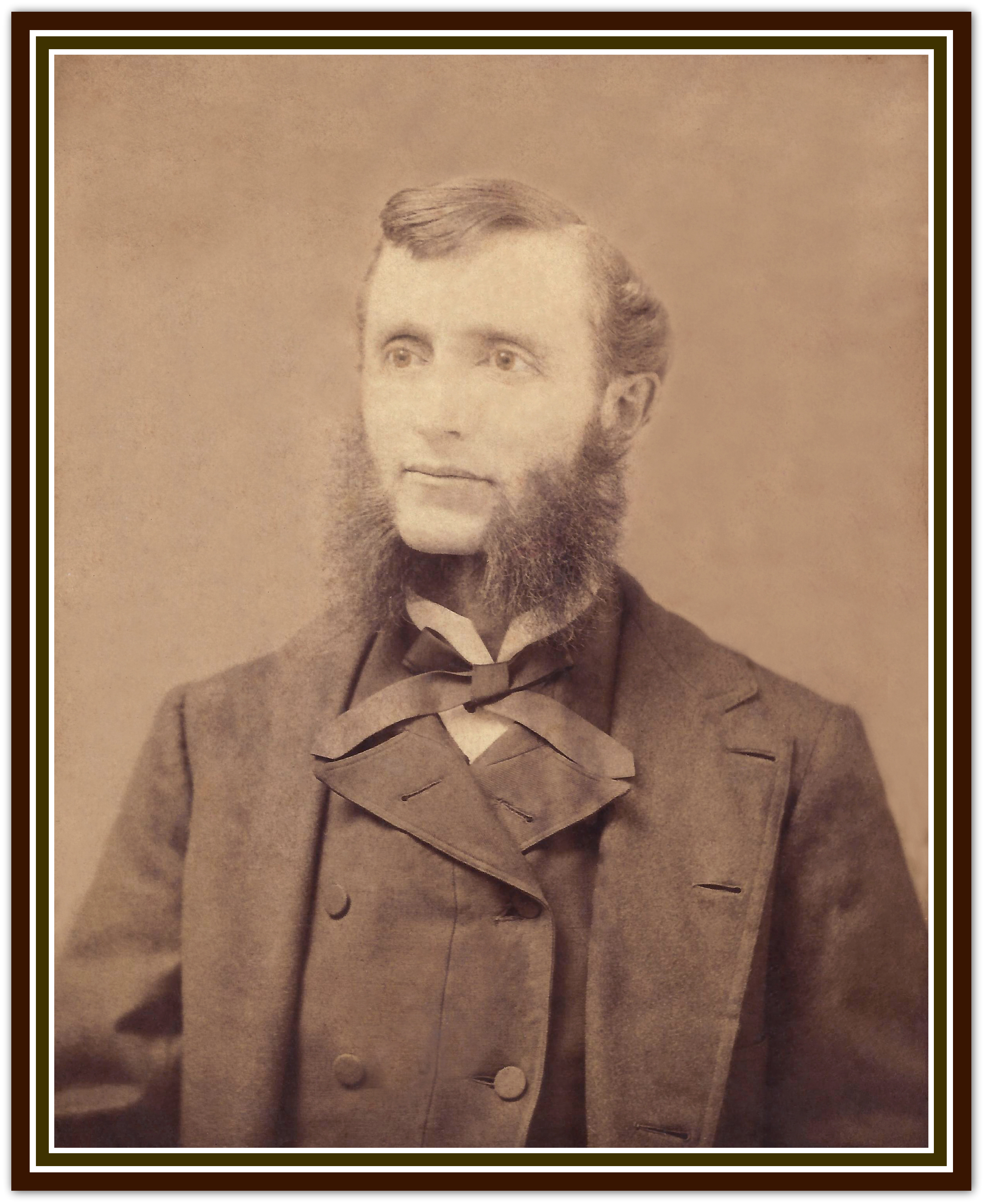

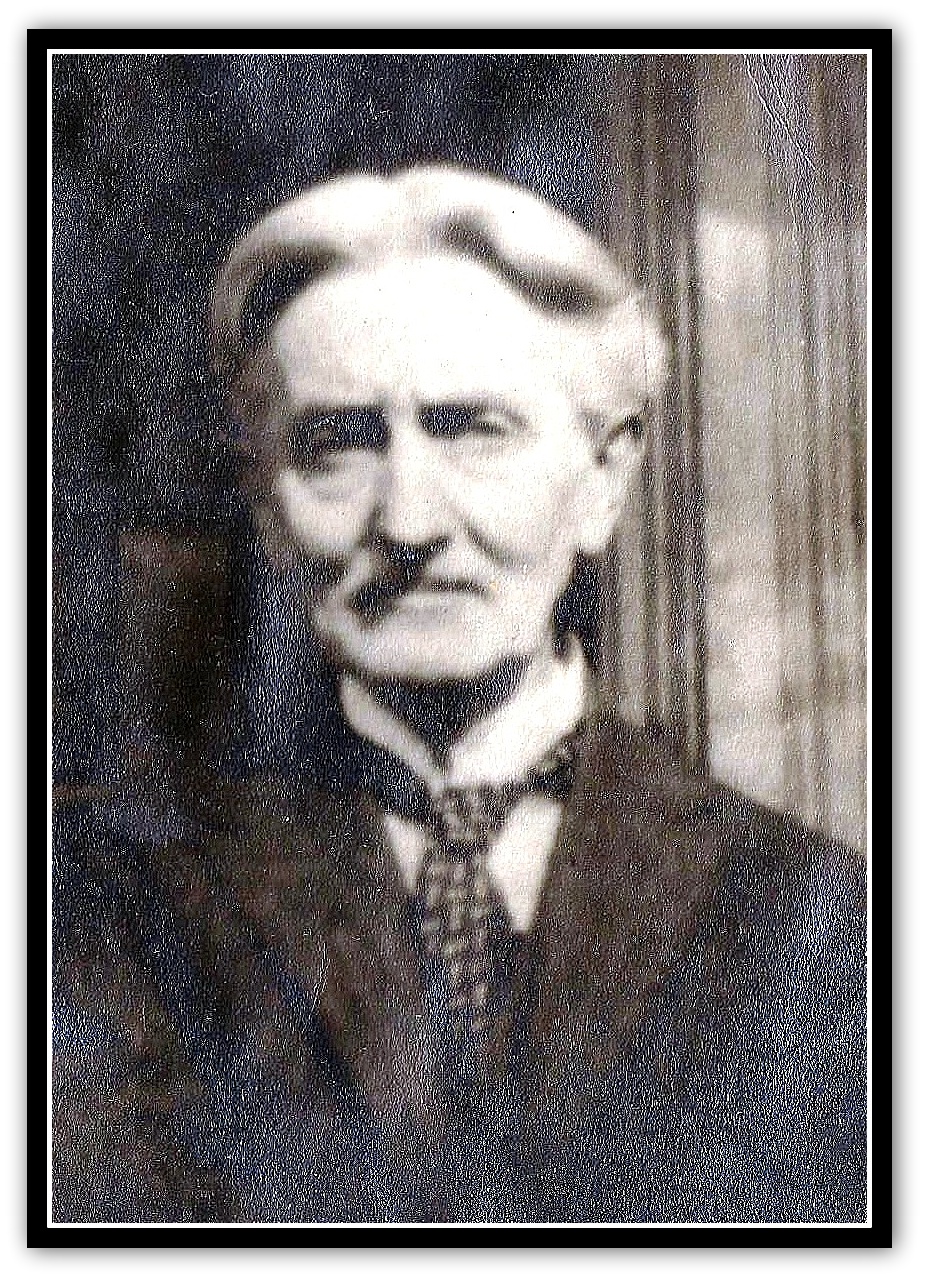

Francis Otto Eggleston, my great-grandfather, lived from about 1915 to 1941 on Glen Road in Woodcliff Lake, New Jersey, a small suburb of New York with leafy green streets that wind down to the lake of the town’s name.

I grew up far from there, in coastal Southern California, but I’ve seen the house on several occasions, on visits back to visit relatives and friends still in the area.

The family that lived in that house consisted of my grandparents, Pearl and Robert Berryman, their two twin boys, Tad and Ted, who would be my uncle and father, and my great-grandparents, Clara and Francis Eggleston.

The family that lived in that house consisted of my grandparents, Pearl and Robert Berryman, their two twin boys, Tad and Ted, who would be my uncle and father, and my great-grandparents, Clara and Francis Eggleston.

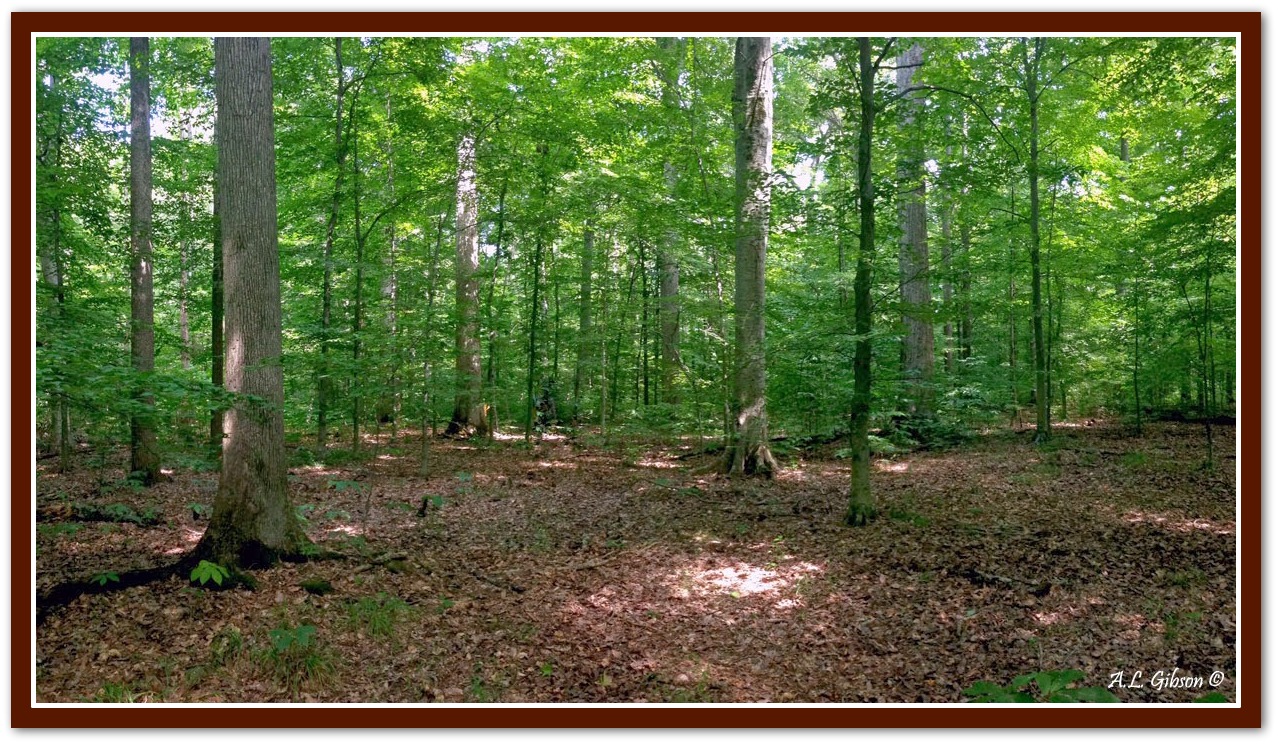

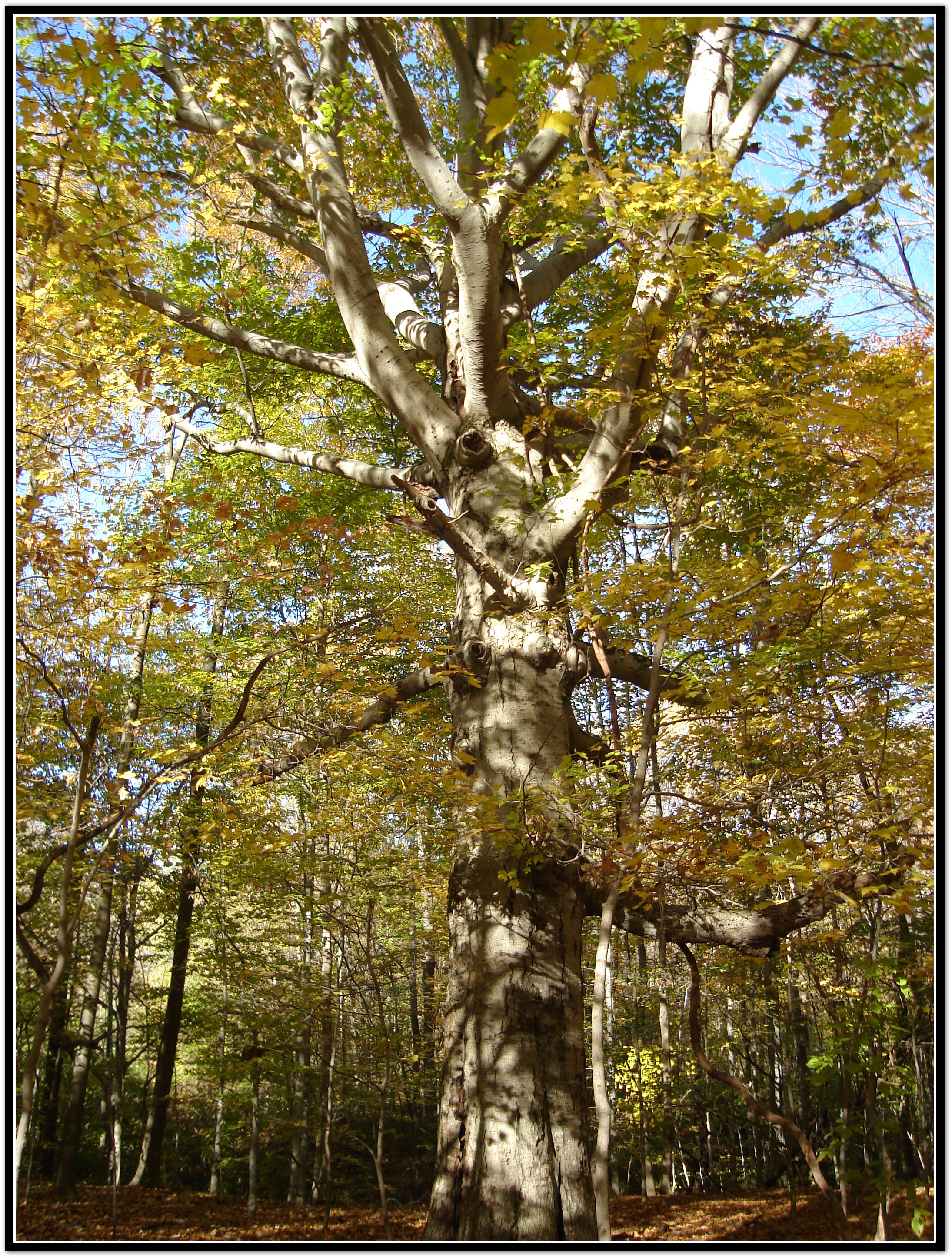

It was a large and stately home with gabled windows and broad eves. There was a curving drive leading to the house in front, and in the back were roses and lilacs, and just beyond, a brook. And of course, there were the trees. Native chestnut, sugar maple, hickory, cedar, and birch shaded the house, and their leaves carpeted the ground down to the creek.

As a child, my father, along with his twin and their younger cousin rigged a “flying boat” with pulleys to swoosh them down and into the creek. It was a massive operation for three boys, but with rope and pulley suspended and secured between two of those deep-rooted hardwood trees, their airborne adventures were ensured.

The children’s parents and grandparents didn’t pay much attention. A few cuts and scrapes, maybe a banged up forehead, were nothing to worry about in a ten or 12-year old boy.

Inside the house my grandmother would be planning one of her frequent parties of artists and political commentators. My great grandfather would be in his study, writing. My grandfather would be at his job in a bank on Wall Street. I’m not sure what Great Grandmother Eggleston would be doing. She was a homemaker all her life, not given to fun in the typical sense, but to quiet serenity.

The house and the trees still stand. The flying boat is long gone, as are my grandparents and great grandparents, my father, his twin, and their cousin.

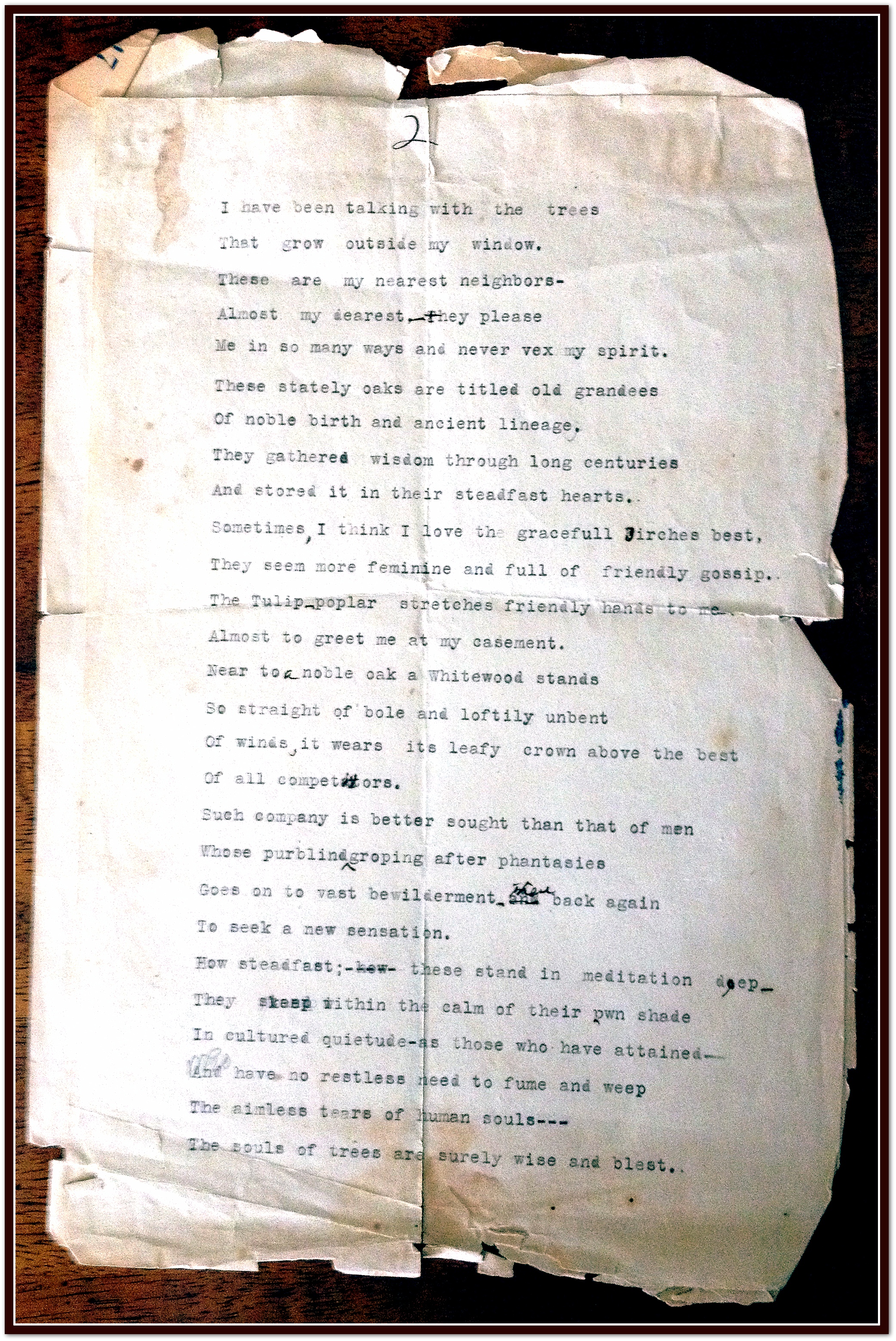

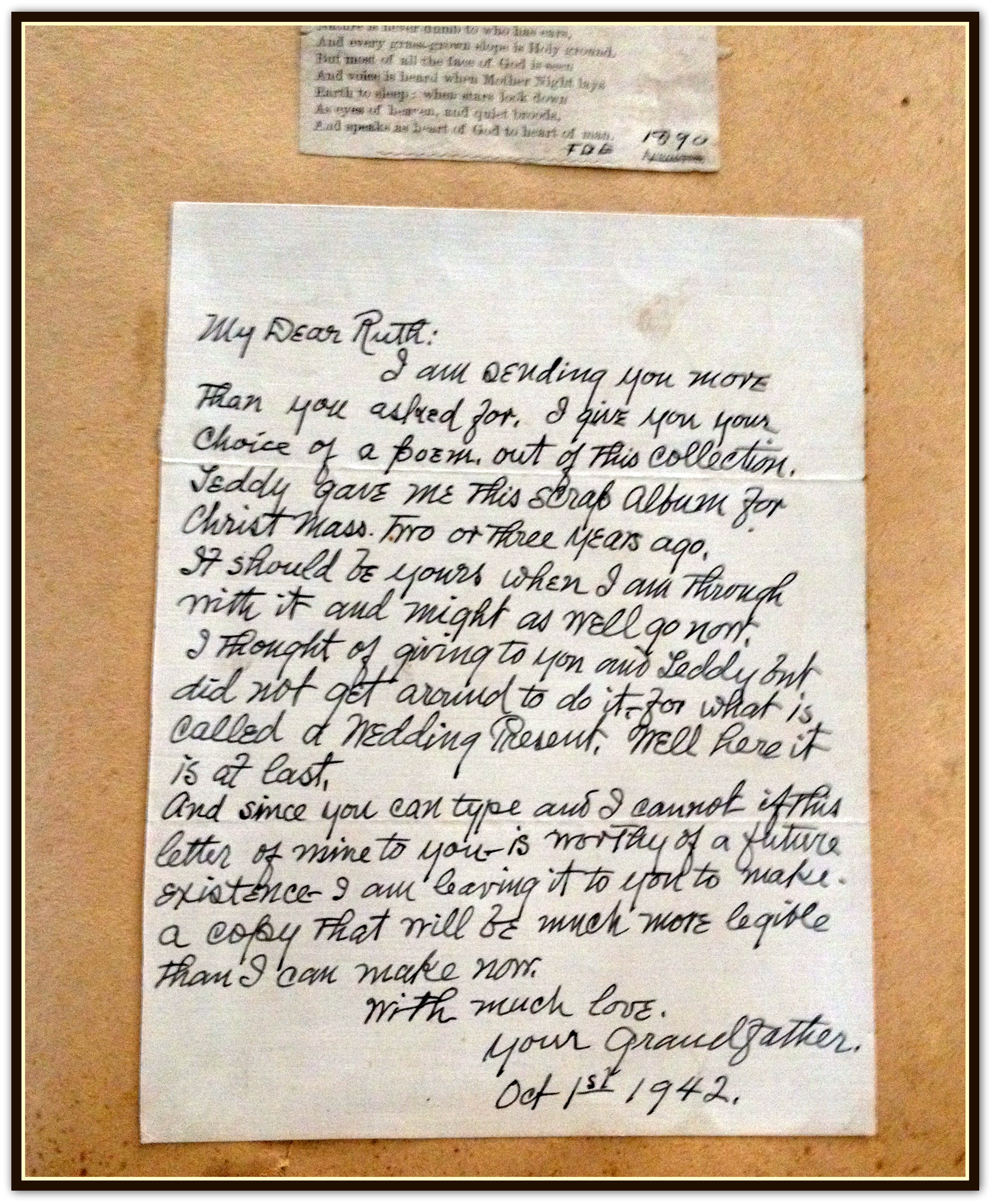

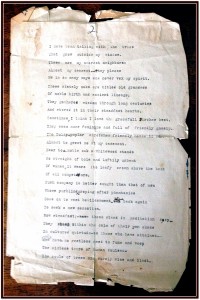

The following poem or meditation was written by Great Grandfather Eggleston, probably when he was in his 70s or 80s and living in this house. Maybe during the day I just described.

I’m afraid it is page two, and I do not have page one. But it is worthwhile reading nonetheless.

Francis Eggleston often signed his poems and articles with simply, F.O.E., including the newspaper column he wrote for the Bergen Record, in Woodcliff Lake, from 1929 through 1941.

A transcription is below the photo.

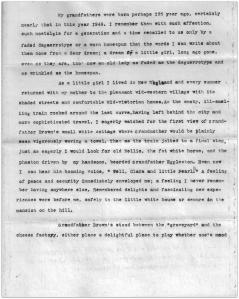

I have been talking with the trees

That grow outside my window.

These are my nearest neighbors –

Almost my dearest – they please

Me in so many ways and never vex my spirit.

These stately oaks are titled old grandees

Of noble birth and ancient lineage.

They gathered wisdom through long centuries

And stored it in their steadfast hearts.

Sometimes, I think I love the graceful birches best,

They seem more feminine and full of friendly gossip.

The Tulip poplar stretches friendly hands to me.

Almost to greet me at my casement.

Near to a noble oak a Whitewood stands

So straight of bole and loftily unbent

Of winds, it wears its leafy crown above the best

Of all competitors.

Such company is better sought than that of men

Whose purblind groping after phantasies

Goes on to vast bewilderment, then back again

To seek a new sensation.

How steadfast; these stand in meditation deep –

They sleep within the calm of their own shade

In cultured quietude – as those who have attained –

Who have no restless need to fume and weep

The aimless tears of human souls —

The souls of trees are surely wise and blest.

F.O.E.

and having the catchy subtitle, Definitions, Descriptions, Illustrations and Methods of Use of the Materials, Equipment and Devices Employed in the Maintenance of the Tracks, Bridges, Buildings, Water Stations, Signals and Other Fixed Properties of Railways.”

and having the catchy subtitle, Definitions, Descriptions, Illustrations and Methods of Use of the Materials, Equipment and Devices Employed in the Maintenance of the Tracks, Bridges, Buildings, Water Stations, Signals and Other Fixed Properties of Railways.”

There were no chestnut trees, but they had hickory trees so big around that a full-grown man could not wrap his arms around them.

There were no chestnut trees, but they had hickory trees so big around that a full-grown man could not wrap his arms around them.

Captive-taking by Native Americans was surprisingly common in Colonial times.

Captive-taking by Native Americans was surprisingly common in Colonial times. nd journalists who sensationalized stories of captor brutality that today’s academics call “capture narratives.”

nd journalists who sensationalized stories of captor brutality that today’s academics call “capture narratives.” Once in the villages, the captives were given Indian clothes, taught Indian songs and dances, and welcomed as family members into specifically appointed adoptive families.

Once in the villages, the captives were given Indian clothes, taught Indian songs and dances, and welcomed as family members into specifically appointed adoptive families.

Of course, they probably weren’t odd for the time, and that’s where it helps to put on your best Sherlock Holmes deerstalker hat and play Ancestral Name Detective.

Of course, they probably weren’t odd for the time, and that’s where it helps to put on your best Sherlock Holmes deerstalker hat and play Ancestral Name Detective. It’s no trick at all to know that my ancestors, Silence Brown, Delight Kent, Mindwell Osborne, Temperance Stewart, and Thankful Clapp were all named in the trendy Puritan practice of choosing virtues as children’s names.

It’s no trick at all to know that my ancestors, Silence Brown, Delight Kent, Mindwell Osborne, Temperance Stewart, and Thankful Clapp were all named in the trendy Puritan practice of choosing virtues as children’s names.

Then someone else started in on adjectives, like Short, Little, Red, or White.

Then someone else started in on adjectives, like Short, Little, Red, or White.