You can see Chapters 1 and 2 of this story here and here.

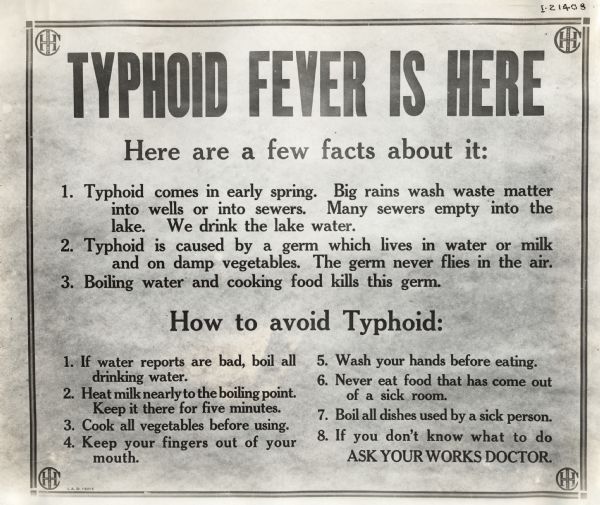

I wrote a few days ago about typhoid fever’s sad visit to the Eggleston home in 1864.

Two of the family’s five members died, my great-grandmother, Abigail Hickox Eggleston, and her young daughter, my great-grand aunt, Mary Eggleston.

Two of the family’s five members died, my great-grandmother, Abigail Hickox Eggleston, and her young daughter, my great-grand aunt, Mary Eggleston.

In that post I did not project myself into the heartbreak that befell the family. It was but a simple account of an event.

Now I’m thinking of the family that was left behind.

How their brand new home felt infinitely empty, the rooms devoid of joy, the air sucked out, the sunlight an intruder on the family’s grief.

I doubt the two boys and one man remaining consoled each other.

That branch of my family was nearly purely of English stock, whose stiff upper lips are their heritage, and further steeled by more than 200 years already on the American frontier, a hard life that could not wait for any sorrow to heal.

There was no bereavement leave on a frontier farm, or any farm. Life must go on, starting at dawn and ending well after dark.

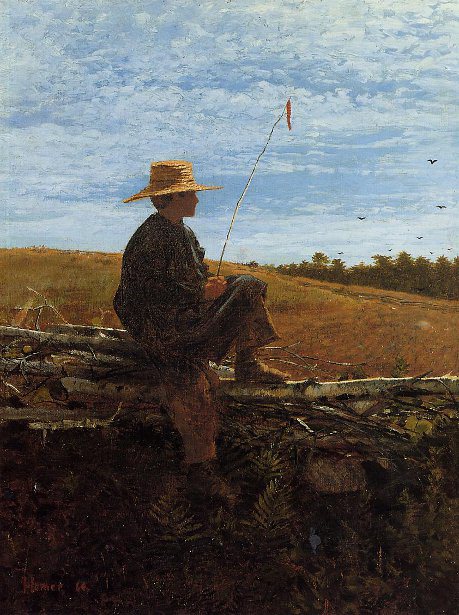

Perhaps that was best, for to be outside at work, or at school, was to be otherwise occupied, not thinking about their sorrow.

Then, upon entering the house at day’s end, that heaviness, that unhealable ache would once again fill their chests.

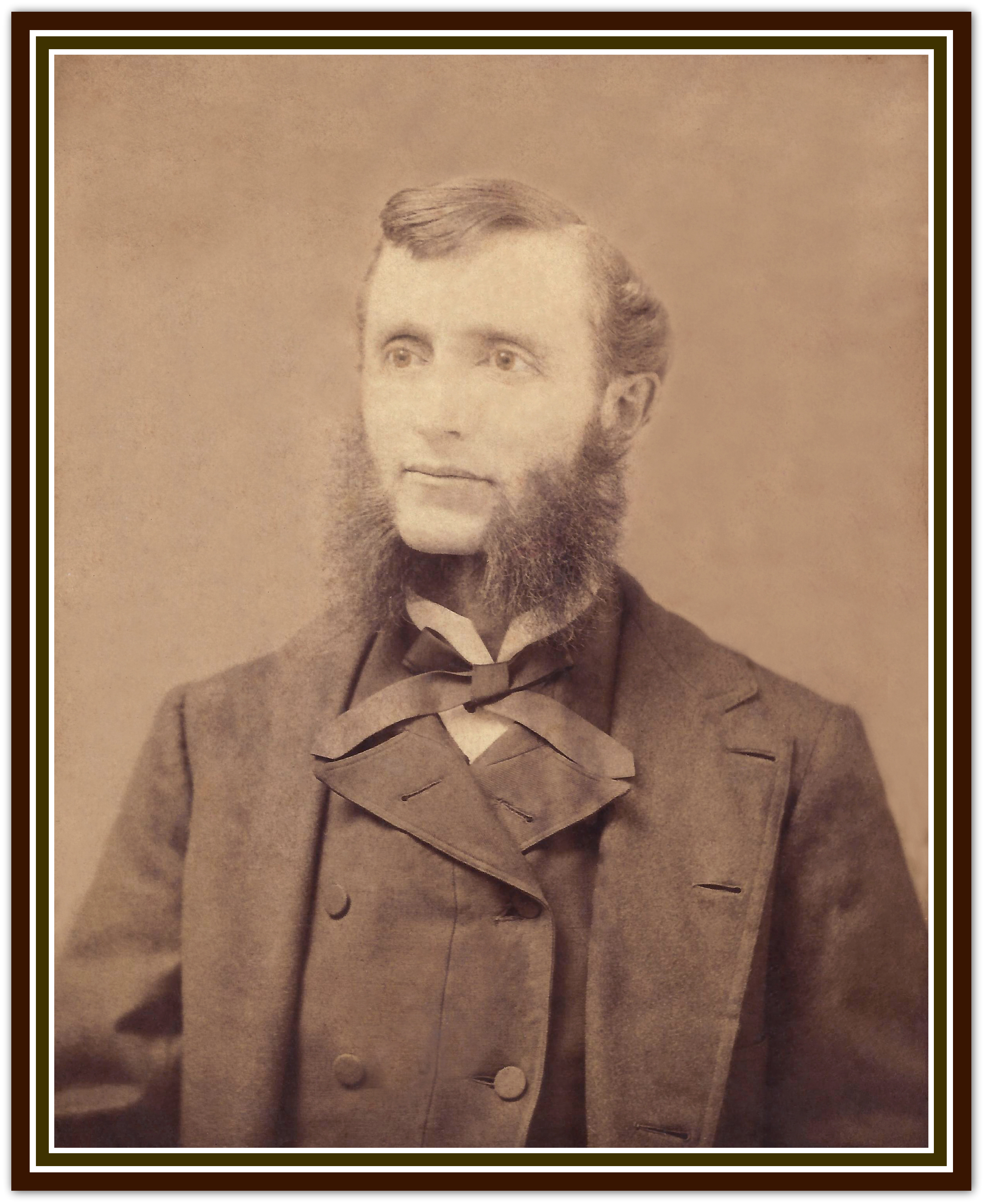

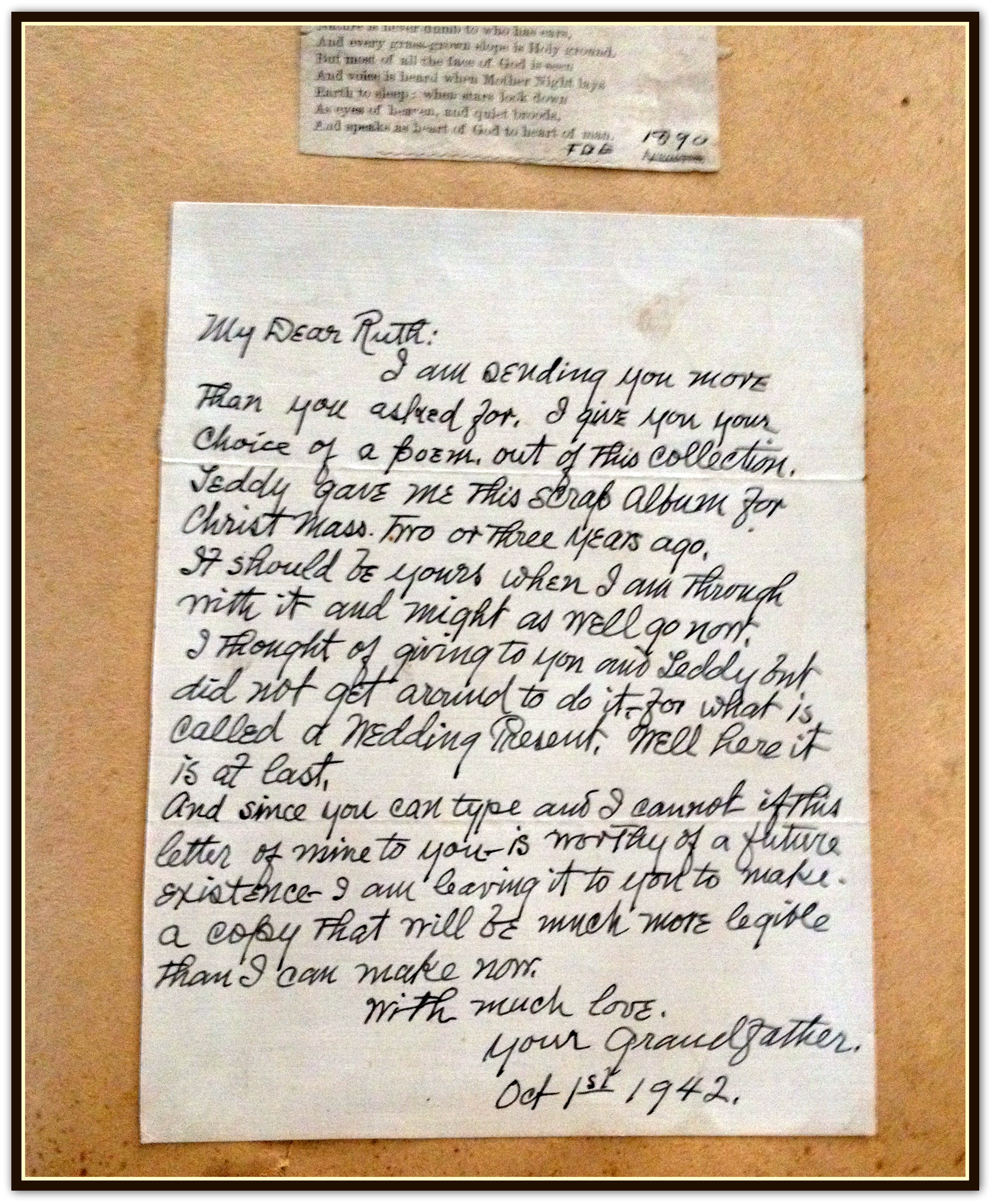

In the biography that my great-grandfather, Francis Eggleston, the youngest boy, wrote many years later he did not write of the sadness, but it is clearly there, behind his words.

He speculates in his biography about what life would have been like had she lived. “What a change there would have been in our family history,” he allowed himself to wonder from the perspective of 89 years.

In those days a family was a machine that ran household, farm, or store.

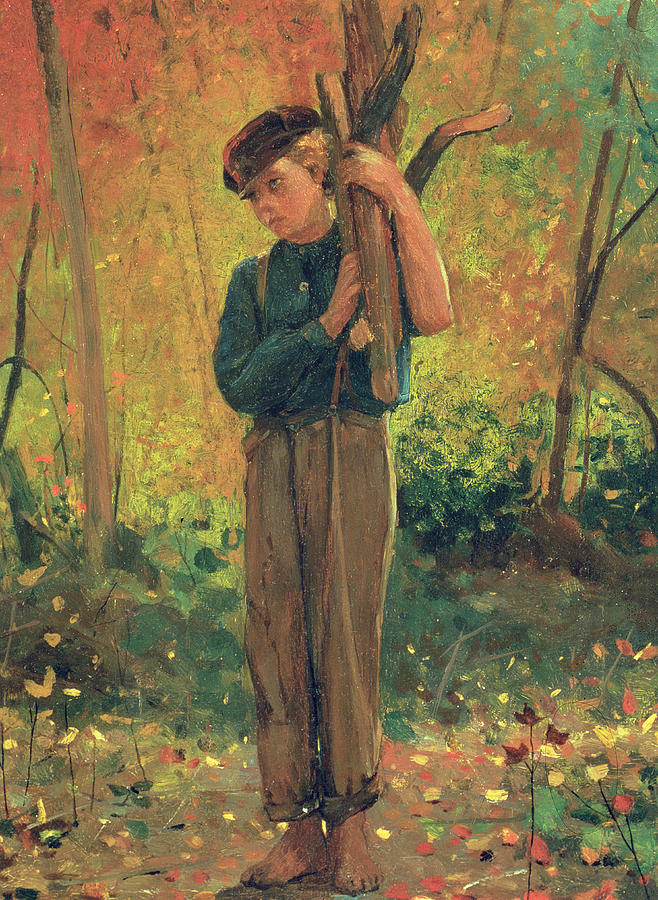

The children tended livestock, carried wood, raked barns, cleaned house and farmyard; they helped in the garden, the fields, the smokehouse, the spring house, and the kitchen.

The children tended livestock, carried wood, raked barns, cleaned house and farmyard; they helped in the garden, the fields, the smokehouse, the spring house, and the kitchen.

The mother lit the fires, cooked, cleaned, boiled water to wash clothes, made soap, kept a kitchen garden with all its hoeing and weeding, sewed clothes, canned for the winter, made jams and apple butter, fed chickens, and helped around the farmyard.

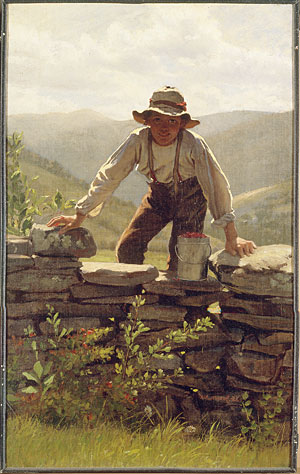

The father did the heavy lifting; he plowed fields, branded and butchered, carpentered, split rails and mended fences, bought and sold land, livestock, and crops, and sometimes had an outside job to make ends meet.

Without any one of those parts, the machine was broken. It wouldn’t work. There was too much to do already, no time or energy to take up someone else’s job duties.

I don’t know if the family had hired help for the house.

I don’t know if the family had hired help for the house.

They were well-to-do by farm standards, and would later own what my grandmother called “the mansion on the hill,” a massive Greek revival that exists to this day.

Maybe after the deaths they a hired woman who helped with the meals and cleaning temporarily.

But a farm could not work properly for long without a full-time mother, and so it was the practice to marry soon after a spouse’s death.

This, great-great grandfather Eggleston did, and so Francis and DeWitt were given a new mother, Mary, who was but three years older than their departed sister would have been.

Did the boys accept her readily, or did they resent her presence?

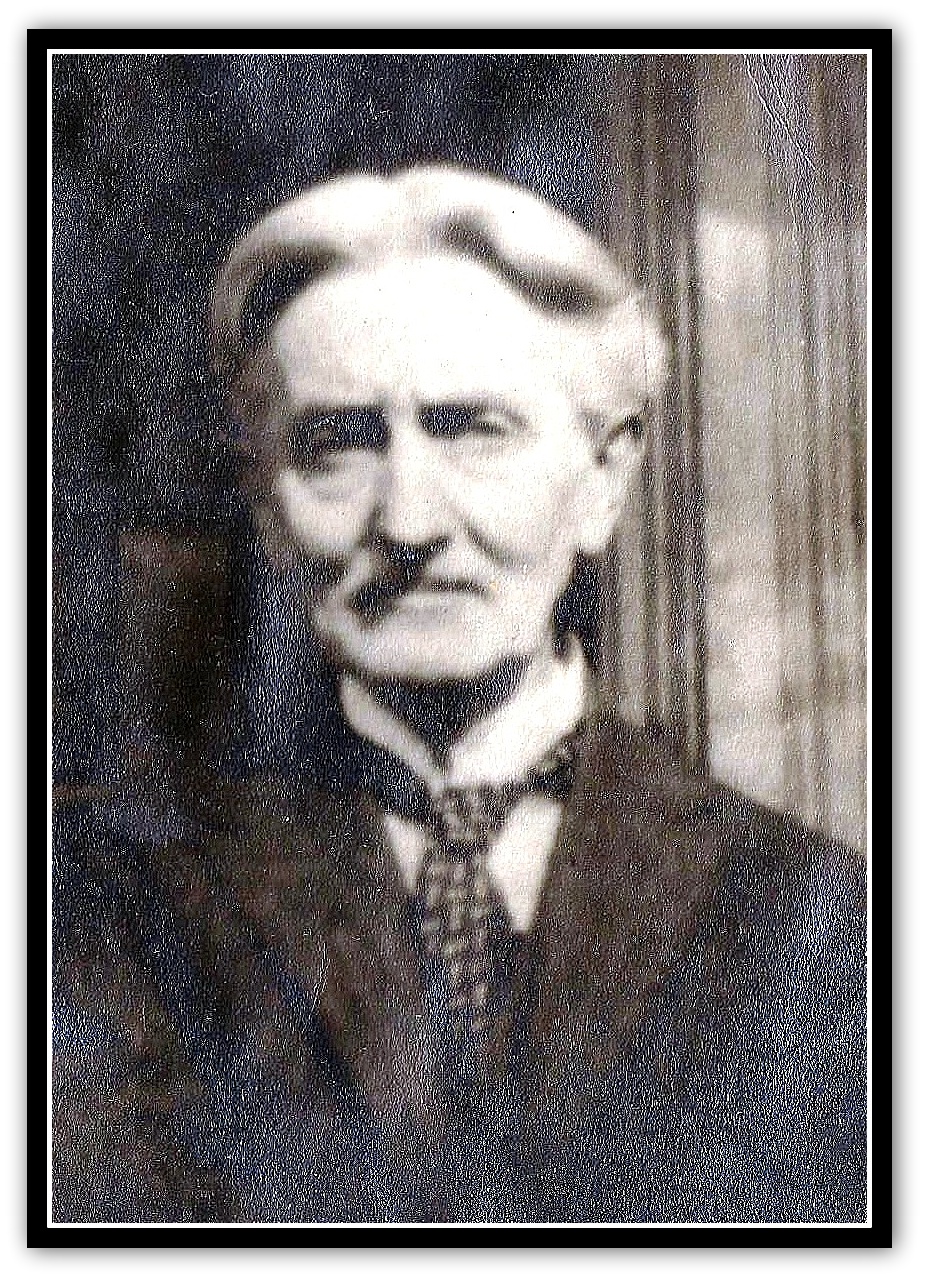

DeWitt, the oldest, was a practical boy, and later a successful businessman. He was 13 when his mother died, and would be off to college in just three years.

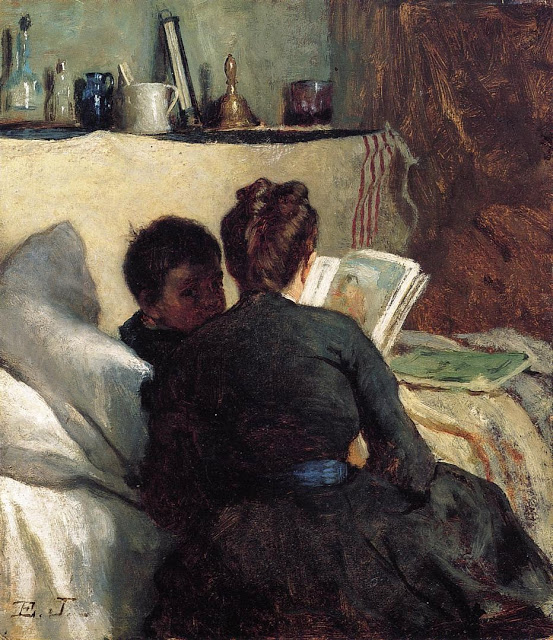

Francis, my great-grandfather, was only ten when his mother died. He was a self-described “poetic and romantic boy,” who “bored my elders with problems too old for my years.”

Perhaps, because of his tender heart, my great-grandfather quietly mourned his mother, but cleaved to this new mother for what affection she offered.

She settled into the family and had two children with the boys’ father, and their marriage lasted more than 50 years before Clinton Eggleston died at 86.

My grandfather also went on to live a long life, dying far from that first home at age 89. Yet in his biography, written in his late ’80s, and even though he was just ten when his mother died, he begins with the typhoid incident on page one.

Clearly his mother’s death left a scar. I’ll never know how deep.

You can read Chapter 4 of Francis Otto Eggleston’s story here.

You can read Chapter 4 of Francis Otto Eggleston’s story here.

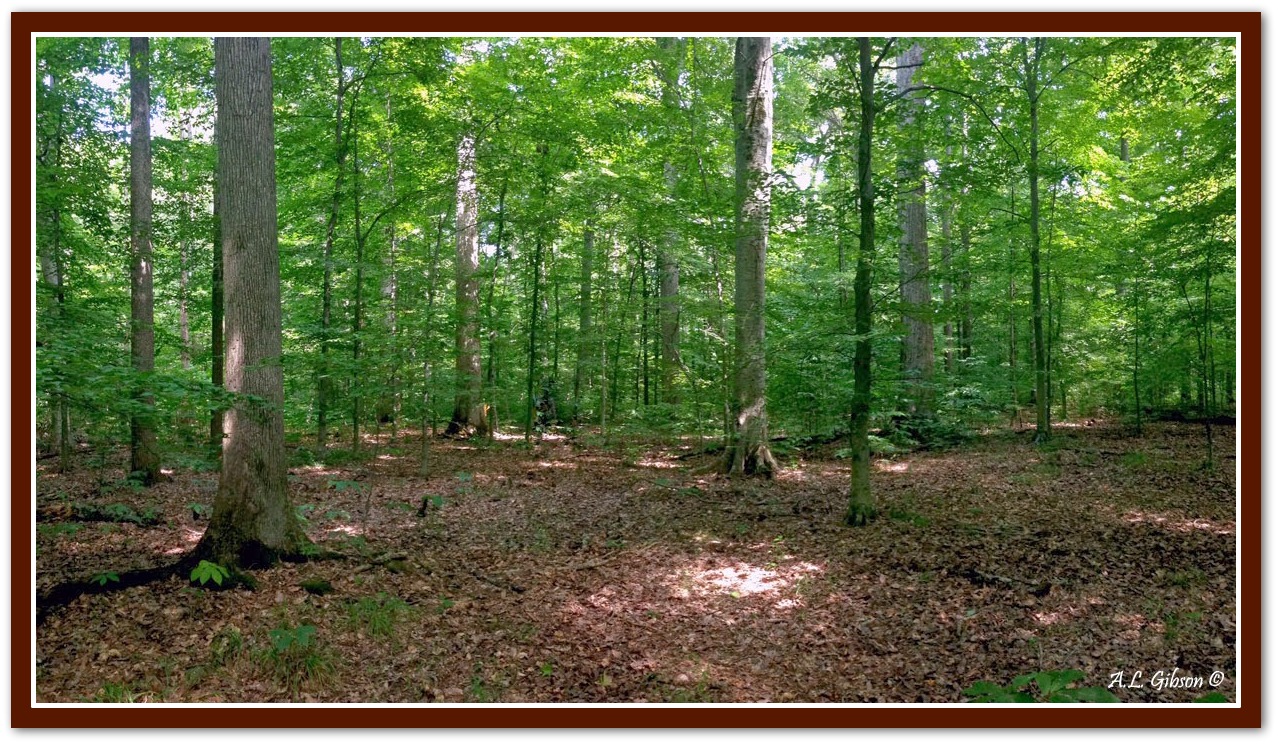

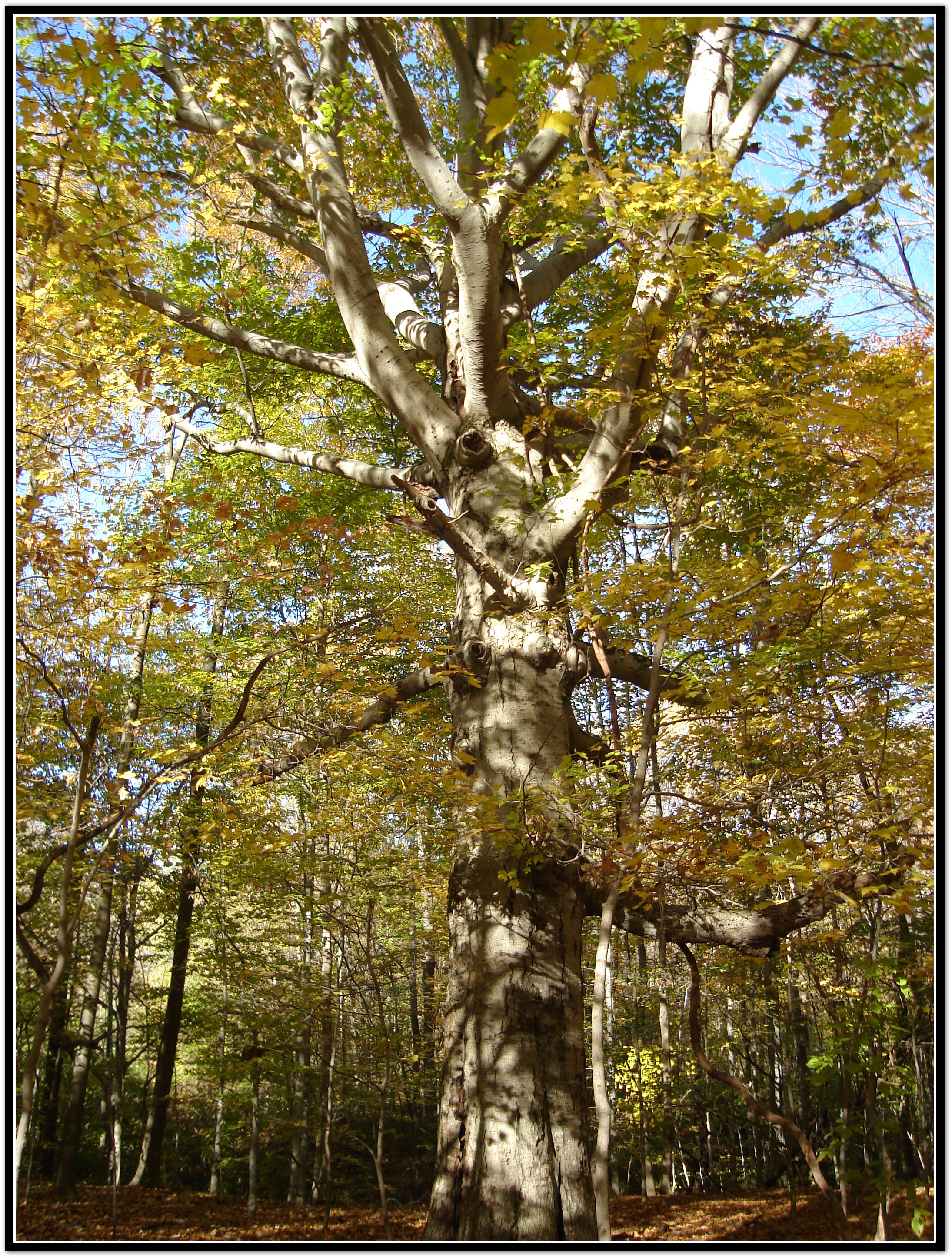

There were no chestnut trees, but they had hickory trees so big around that a full-grown man could not wrap his arms around them.

There were no chestnut trees, but they had hickory trees so big around that a full-grown man could not wrap his arms around them.

Recovery for the others was complete, and my great-grandfather suffered no long-lasting ill effects from the disease, other than the tragic loss of mother and sister, who I am sure he mourned for all his life.

Recovery for the others was complete, and my great-grandfather suffered no long-lasting ill effects from the disease, other than the tragic loss of mother and sister, who I am sure he mourned for all his life.