On my father’s side I come from a long line of Boyds. So far so good. But things happen to Boyds that make me want to look over my shoulder now and then just for having Boyd blood.

Of course, things happen to every family, but when they happen to Boyds they tend to be so big or tragic or astonishing that they are recorded in history books.

This story tells only one of them.

Starting with Robert dictus de Boyd in 1262, the Scottish Boyds ascended to nobility…were given a castle…were accused of treason…lost their castle…were literally stabbed in the back…regained Royal favor and a few more castles…were imprisoned in the Tower of London…executed… mortified… regained favor again…and were generally kicked about like royal hacky sacks for some 500-odd years.

Then, in 1746 Sir William Boyd was executed for attempting to take the British Crown.  Meanwhile, half a world away in the wilds of Pennsylvania, John and Nancy Boyd were about to have their lives ripped apart.

Meanwhile, half a world away in the wilds of Pennsylvania, John and Nancy Boyd were about to have their lives ripped apart.

In the mid-1700s my Scots-Irish ancestors came to America in search of a place where the land would sustain them.

Where they could build a home, raise a family, and live in peace, far from the volatile mess in their homeland.

John Boyd and Nancy Urie thought they found it in the unbroken wilderness of Pennsylvania’s Cumberland Valley.

John Boyd and Nancy Urie thought they found it in the unbroken wilderness of Pennsylvania’s Cumberland Valley.

They cut their plot of land from the forest, built a log cabin, and commenced living the hard but independent life of a frontier family.

John was a farmer, and a few miles away lived his neighbor, John Stewart, a weaver.

On February 10, 1756, John and his oldest son, William, started out for Stewart’s to buy a web of cloth.

On February 10, 1756, John and his oldest son, William, started out for Stewart’s to buy a web of cloth.

With five active children and a new one on the way, Nancy Urie Boyd needed plenty of cloth to sew, one stitch at a time, into clothes.

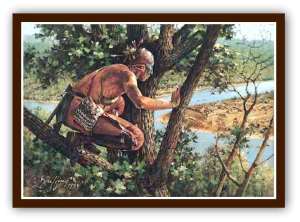

David Boyd was a responsible boy of 13, and after his father left for Stewart’s, his mother sent David out to chop wood.

He took his hatchet, and his little brother John, who was six, went along to pick up chips.

Their two sisters, Sallie and Rhoda, ten and seven, stayed inside with their mother and little brother.

Their two sisters, Sallie and Rhoda, ten and seven, stayed inside with their mother and little brother.

David got busy with the wood, and his hatchet rang out through the forest.

He put all his concentration on placing the hatchet perfectly straight into the log, splitting it right through the middle.

He was concentrating so hard, in fact, that he didn’t hear the Iroquois Indian who had walked right up to him.

He was concentrating so hard, in fact, that he didn’t hear the Iroquois Indian who had walked right up to him.

But little John did, and he screamed. David turned, but it was too late.

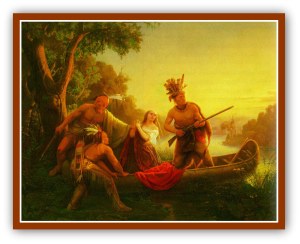

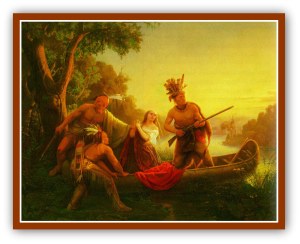

The Iroquois grabbed David by his belt, threw him over his shoulder, and ran off into the forest.

John was snatched the same way, and in seconds the two boys disappeared into the trees.

Within moments Sally and Rhoda and their little brother, not yet three, were taken, and all five of them were brought together a short ways off.

The Natives instructed the children to run.

The Natives instructed the children to run.

As he ran, David looked back to see his agonized mother standing before their home in flames, her hands raised to the heavens, praying, “O God, be merciful to my children going among these savages.”

The party of Natives that took the Boyd children also took their mother after setting the cabin to flames.

They drove the party on until the pregnant mother and smallest child could go no more, and so they were killed along the trail.

The children were traumatized. But they did as their captors told them, running on the trail, always running, and staying silent.

The children were traumatized. But they did as their captors told them, running on the trail, always running, and staying silent.

And so they survived and were taken hundreds of miles into the Ohio Territory, and there they were separated and given to different tribes.

But they were not made to be prisoners in the way we usually understand the term.

You would think that a captor brutal enough to slaughter a babe before his mother and a mother before her children could not show humanity.

You would think that a captor brutal enough to slaughter a babe before his mother and a mother before her children could not show humanity.

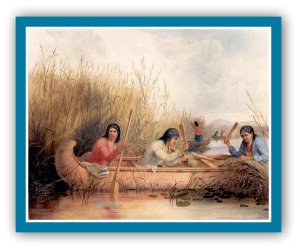

But the Boyd children were adopted by the community and given new parents who taught the children this different way of life.

They ate and slept alongside these Iroquois and Delaware people.

They helped to hunt or prepare food, to care for babies and elders, sew shirts, haul firewood, prepare herbal medicine.

T hey learned lessons of the forest and the stars and the animals. They became what people of the day called white Indians.

hey learned lessons of the forest and the stars and the animals. They became what people of the day called white Indians.

After living in the tribe for four years, David Boyd’s adoptive Delaware father decided it was time to return him to his white family.

David hesitated. This had become his new family, and he liked his new life.

He went reluctantly and was reunited with his father, John Boyd.

Twice thereafter he attempted to flee back to his Delaware family, but was brought back each time, and eventually he married a white woman, settled down, and had ten children.

Rhoda Boyd was rescued by the famous captive hunter, Colonel Bouquet.

But on the trip to Fort Pitt, where she was to be reunited with family, she escaped to her Native family, and never returned to white society.

But on the trip to Fort Pitt, where she was to be reunited with family, she escaped to her Native family, and never returned to white society.

Sallie was returned to her father on February 10, 1764. John was returned on November 15 that same year, along with his brother, Thomas.

That was exactly 250 years ago. I don’t know of any Boyd tragedies of the kind that make history that have happened since then. My family left the Boyd line behind with my great-grandmother, Sarah Columbia Boyd.

Perhaps the Boyd family can rest now.

There are numerous differing accounts of the Boyd capture. I chose to follow what seems the most credible source, the book Setting All the Captives Free, by the scholar, Ian K. Steele.

Like this:

Like Loading...

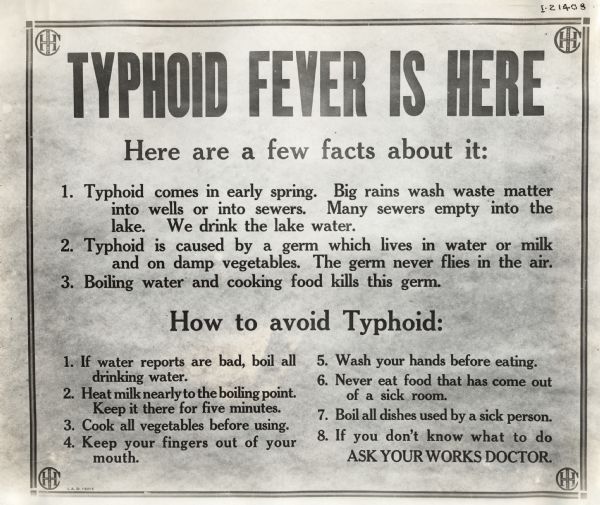

Recovery for the others was complete, and my great-grandfather suffered no long-lasting ill effects from the disease, other than the tragic loss of mother and sister, who I am sure he mourned for all his life.

Recovery for the others was complete, and my great-grandfather suffered no long-lasting ill effects from the disease, other than the tragic loss of mother and sister, who I am sure he mourned for all his life.

Captive-taking by Native Americans was surprisingly common in Colonial times.

Captive-taking by Native Americans was surprisingly common in Colonial times. nd journalists who sensationalized stories of captor brutality that today’s academics call “capture narratives.”

nd journalists who sensationalized stories of captor brutality that today’s academics call “capture narratives.” Once in the villages, the captives were given Indian clothes, taught Indian songs and dances, and welcomed as family members into specifically appointed adoptive families.

Once in the villages, the captives were given Indian clothes, taught Indian songs and dances, and welcomed as family members into specifically appointed adoptive families.

John Boyd and Nancy Urie thought they found it in the unbroken wilderness of Pennsylvania’s Cumberland Valley.

John Boyd and Nancy Urie thought they found it in the unbroken wilderness of Pennsylvania’s Cumberland Valley. On February 10, 1756, John and his oldest son, William, started out for Stewart’s to buy a web of cloth.

On February 10, 1756, John and his oldest son, William, started out for Stewart’s to buy a web of cloth. Their two sisters, Sallie and Rhoda, ten and seven, stayed inside with their mother and little brother.

Their two sisters, Sallie and Rhoda, ten and seven, stayed inside with their mother and little brother. He was concentrating so hard, in fact, that he didn’t hear the Iroquois Indian who had walked right up to him.

He was concentrating so hard, in fact, that he didn’t hear the Iroquois Indian who had walked right up to him. The Natives instructed the children to run.

The Natives instructed the children to run. The children were traumatized. But they did as their captors told them, running on the trail, always running, and staying silent.

The children were traumatized. But they did as their captors told them, running on the trail, always running, and staying silent. You would think that a captor brutal enough to slaughter a babe before his mother and a mother before her children could not show humanity.

You would think that a captor brutal enough to slaughter a babe before his mother and a mother before her children could not show humanity. hey learned lessons of the forest and the stars and the animals. They became what people of the day called white Indians.

hey learned lessons of the forest and the stars and the animals. They became what people of the day called white Indians.