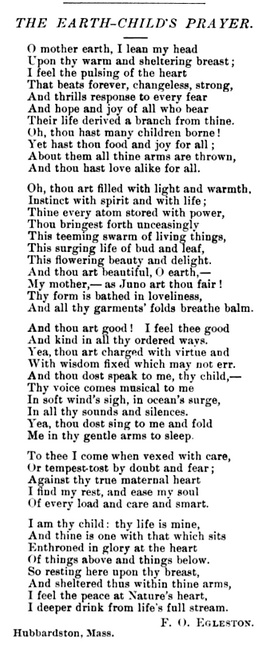

I just remembered a poem written by my great grandfather, Francis O. Eggleston. It is a perfect Earth Day poem, written some time before 1900.

I just remembered a poem written by my great grandfather, Francis O. Eggleston. It is a perfect Earth Day poem, written some time before 1900.

You can see Chapters 1 and 2 of this story here and here.

I wrote a few days ago about typhoid fever’s sad visit to the Eggleston home in 1864.

Two of the family’s five members died, my great-grandmother, Abigail Hickox Eggleston, and her young daughter, my great-grand aunt, Mary Eggleston.

Two of the family’s five members died, my great-grandmother, Abigail Hickox Eggleston, and her young daughter, my great-grand aunt, Mary Eggleston.

In that post I did not project myself into the heartbreak that befell the family. It was but a simple account of an event.

Now I’m thinking of the family that was left behind.

How their brand new home felt infinitely empty, the rooms devoid of joy, the air sucked out, the sunlight an intruder on the family’s grief.

I doubt the two boys and one man remaining consoled each other.

That branch of my family was nearly purely of English stock, whose stiff upper lips are their heritage, and further steeled by more than 200 years already on the American frontier, a hard life that could not wait for any sorrow to heal.

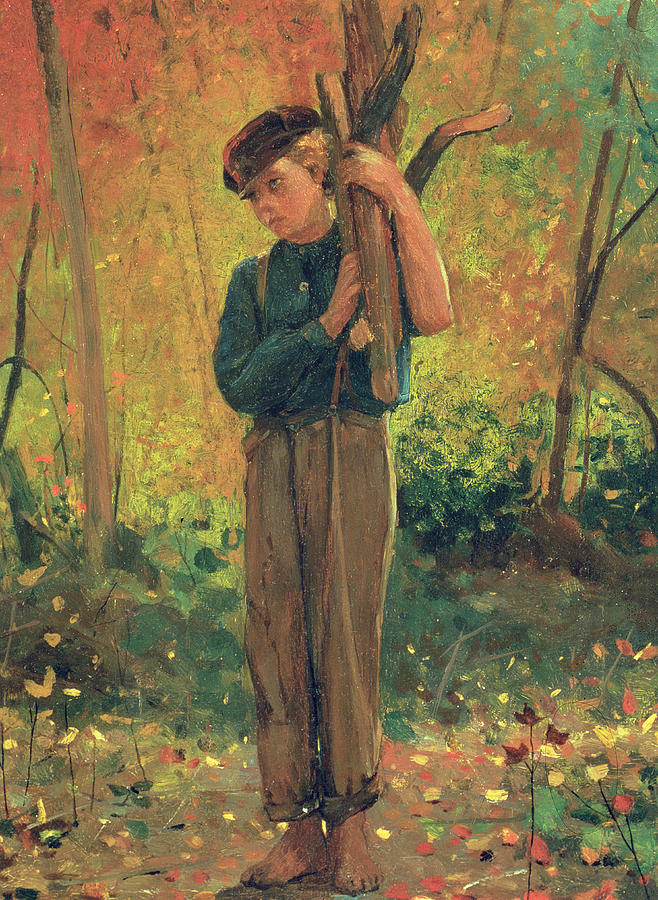

There was no bereavement leave on a frontier farm, or any farm. Life must go on, starting at dawn and ending well after dark.

Perhaps that was best, for to be outside at work, or at school, was to be otherwise occupied, not thinking about their sorrow.

Then, upon entering the house at day’s end, that heaviness, that unhealable ache would once again fill their chests.

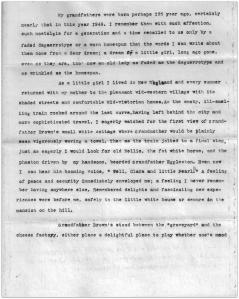

In the biography that my great-grandfather, Francis Eggleston, the youngest boy, wrote many years later he did not write of the sadness, but it is clearly there, behind his words.

He speculates in his biography about what life would have been like had she lived. “What a change there would have been in our family history,” he allowed himself to wonder from the perspective of 89 years.

In those days a family was a machine that ran household, farm, or store.

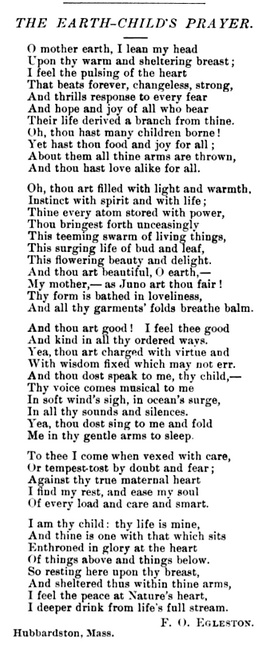

The children tended livestock, carried wood, raked barns, cleaned house and farmyard; they helped in the garden, the fields, the smokehouse, the spring house, and the kitchen.

The children tended livestock, carried wood, raked barns, cleaned house and farmyard; they helped in the garden, the fields, the smokehouse, the spring house, and the kitchen.

The mother lit the fires, cooked, cleaned, boiled water to wash clothes, made soap, kept a kitchen garden with all its hoeing and weeding, sewed clothes, canned for the winter, made jams and apple butter, fed chickens, and helped around the farmyard.

The father did the heavy lifting; he plowed fields, branded and butchered, carpentered, split rails and mended fences, bought and sold land, livestock, and crops, and sometimes had an outside job to make ends meet.

Without any one of those parts, the machine was broken. It wouldn’t work. There was too much to do already, no time or energy to take up someone else’s job duties.

I don’t know if the family had hired help for the house.

I don’t know if the family had hired help for the house.

They were well-to-do by farm standards, and would later own what my grandmother called “the mansion on the hill,” a massive Greek revival that exists to this day.

Maybe after the deaths they a hired woman who helped with the meals and cleaning temporarily.

But a farm could not work properly for long without a full-time mother, and so it was the practice to marry soon after a spouse’s death.

This, great-great grandfather Eggleston did, and so Francis and DeWitt were given a new mother, Mary, who was but three years older than their departed sister would have been.

Did the boys accept her readily, or did they resent her presence?

DeWitt, the oldest, was a practical boy, and later a successful businessman. He was 13 when his mother died, and would be off to college in just three years.

Francis, my great-grandfather, was only ten when his mother died. He was a self-described “poetic and romantic boy,” who “bored my elders with problems too old for my years.”

Perhaps, because of his tender heart, my great-grandfather quietly mourned his mother, but cleaved to this new mother for what affection she offered.

She settled into the family and had two children with the boys’ father, and their marriage lasted more than 50 years before Clinton Eggleston died at 86.

My grandfather also went on to live a long life, dying far from that first home at age 89. Yet in his biography, written in his late ’80s, and even though he was just ten when his mother died, he begins with the typhoid incident on page one.

Clearly his mother’s death left a scar. I’ll never know how deep.

You can read Chapter 4 of Francis Otto Eggleston’s story here.

You can read Chapter 4 of Francis Otto Eggleston’s story here.

Sometimes when I’m writing genealogy a veil of loneliness falls over me, like walking through a misty cemetery at dusk.

It’s when I come across an ancestor who left barely any record of having lived. Just a name in the family bible. Or a lone census record that says she did indeed live, in a place, in a certain year.

Or, as it is with one of my ancestors, there is nothing but a name on a handwritten list of family members who sequentially possessed a family heirloom that eventually came to me.

There is no other sign she existed. No census record, church record, marriage record… nothing. I don’t have her maiden name, only her married one, and so do not even know which line to follow, though I’ve tried the likely ones, to no avail.

It’s then that a sadness comes, not because of my research failure, but because that person’s life left no apparent trace. It’s as if they lived so lightly that their footprints made no impression on the world.

Perhaps some personal record of their life is with another descendant, not me. Or, horribly, perhaps their memories were tossed in the dustbin of history, like Leon Trotsky’s Mensheviks.

I’ve been in second-rate antique stores, the kind that stuff a large bit of everything into a space too small, where in some hard-to-reach corner of the shop there is a cardboard box filled with old studio portraits. Solemn wedding pictures from the 19th century, hand-colored photos of precious children, dignified portraits of a family elder. Who are these people, and why did they end up in this sad place?

For how long were they remembered before an uninterested great-grandson or step-niece tossed their photo in a box and stuffed it into the back of a closet, to be passed down eventually to another generation who couldn’t possibly even dream of taking the time to search out who those people might be?

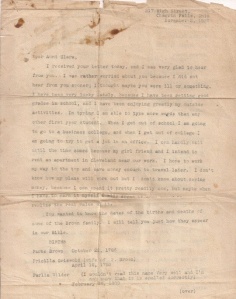

I have a box like that. For years it actually was a cardboard box. It’s where we kept our family photos when I was a child. When we sold our parents’ house the box came to me, and I hauled it around for years, first to one house, then another, where it would reside in a closet until we moved yet again.

It wasn’t because of dishonor to our ancestors that the photos were closeted in an old cardboard box. It was just because our home was a madhouse. When she was very old, my grandmother took the photos and attempted to organize them into an album. She used glue to stick them onto black paper. Then she turned to the next page, smashing the two previous facing pages together, and the still-wet glue adhered to the photo opposite it. This went on for the entire album.

Later, we tried to peel the photos from the paper, to varying results. The survivors went into another album, the victims into the box. As a child I liked to get out the box and look through the photos. My sister and I would occasionally scribble on the backs of them. Then we’d toss them back in, sideways, upside down, crumpled, whatever.

Now I’m restoring all these photos – to great success, I might add, using a young professional restorer in Romania who has worked magic (leave a note in the comments section if you want her contact info.)

I have identified nearly all of the ancestors in these photos. But a few still stare hauntingly at me from the box, wanting me to restore their names. Then that sadness comes. I feel nearly like these inanimate objects are lonely. Patently ridiculous, of course, but still….

I have identified nearly all of the ancestors in these photos. But a few still stare hauntingly at me from the box, wanting me to restore their names. Then that sadness comes. I feel nearly like these inanimate objects are lonely. Patently ridiculous, of course, but still….

Is that my fear of mortality? I didn’t think I had that fear. I’ve never thoroughly understood some people’s drive to leave a lasting impression on the world. Shouldn’t that be a byproduct of some objective, not one’s raison d’etre?

I don’t mind the sadness. There’s quiet in it. And empathy. It connects me to the person I’m researching. And it lifts when I finally fill in the blanks of their life, if I’m so lucky.

My husband occasionally tells me I think too much. He says I have a “busy brain.” But he’s never said I feel too much. That’s a good thing.

Why do we do it?

Why do we spend our time digging into the past, an exercise that is sure not to change the world in any meaningful way?

Why do we spend hours on end combing through dusty stacks or tussling with software that won’t bend to our will?

Why do we spend hours on end combing through dusty stacks or tussling with software that won’t bend to our will?

I know my answer. It’s simple. Because someone has to do it.

It’s because I have all of my birth family’s photos and memorabilia, and my siblings have hounded me for years to make copies for them, so I’m finally getting around to it.

But that’s not the real answer, is it? We both know it.

There’s a reason I’m the one who ended up with all the photos, after all. Because I have always been the one who has her nose stuck in old journals of my great-great grandfather or who sits picking through dog-earred photos of my un-labeled ancestral strangers that someone shoved in a box and forgot about long ago.

I go after my ancestors with bloodhound-like dedication.

It’s a way of grounding myself, of adding to my understanding of who I am. I want connection, I seek connection to the past “me’s.”

Because as much as I am an individual, I am also an amalgamation of all those who came before me.

Because as much as I am an individual, I am also an amalgamation of all those who came before me.

That’s heredity. The simple idea that some of my traits – and maybe some of my most important traits – come from my birth family.

And so where did they come from?

A family line may pass down so much more than DNA-dependent traits.

A family passes down its way of looking at and living in the world. And if you’ve ever wondered why you do something a certain way, maybe it’s because of your great-great-grandfather.

At family get togethers my grandfather, always political and with a wry sense of humor, used to get the kids around him, and lead us in singing, “Vote the Democratic party in November, if you want to go to heaven when you die.” It still makes me laugh!

Through genealogical research I know now that he was raised by a staunch Democrat, who was in turn raised by another staunch Democrat.

There is a book I found called History of Allen County, Ohio, and Representative Citizens, published in 1906.

In it I found a sketch about my great-grandfather saying, “Like his father, he is a Democrat, and has served as school director, justice of the peace, trustee, assessor and supervisor.”

In it I found a sketch about my great-grandfather saying, “Like his father, he is a Democrat, and has served as school director, justice of the peace, trustee, assessor and supervisor.”

Now I know that I come from at least four generations of staunch Democrats, and if I look hard enough maybe I can trace the propensity back further.

Family “traits” can take strange turns, too.

I heard a story one time about a family whose tradition it was to cut the Christmas ham in half before cooking it. That’s the way it was done and no one questioned why.

But a young member of the of the family asked. Her mother didn’t know, nor did her aunts, who all cut the ham thus so before baking as well.

So she asked her grandmother, and learned that as a young bride she had a small oven, and needed to cut the ham in two for it to fit.

These are the delightful stories we can uncover when we take interest in our forebears.

But does the information have any use to us? Probably not in proportion to the amount of work it takes to find it.

But that’s just talking in practicalities. It’s not “practical” to want to know more about yourself.

It’s not “practical” to spend your time digging through your past when you “should” be straightening a messy house or putting in a few extra hours at work.

That’s okay. I’m a self-diagnosed progonoplexic.

Progonoplexia is a condition marked by obsession with one’s ancestors.

It was coined to describe the modern Greek people’s preoccupation with their ancient past.

But heck, if those monuments and statues and writers and philosophers were mine, I’d be obsessed too. If one must be obsessed with anything, ancient Greece is one of the healthier choices I can think of.

I’m not sure I can say I’m “obsessed” with my past. But there is a great sense of satisfaction in discovering my forebears. Especially the ones of just two or three generations ago, near enough to have made a big difference in who I am.

Yes, I am a staunch Democrat, like my father and grandfather and great-grandfather and great-great grandfather.

Yes, I am a staunch Democrat, like my father and grandfather and great-grandfather and great-great grandfather.

I also have a “tender heart” like my grandmother, or so says my mother.

I have courage, like my great uncle, who after shooting a grizzly bear in Alaska but being injured in the process and unable to make it back to camp, opened and slept inside the bear. (But I’ll go on record as saying I’m not that brave!)

And I am easily frustrated and distracted, like the great-grandfather who up and left his family and never returned. Again, the trait in me is diluted. I’m not that easily frustrated, but I’ve been told I don’t suffer fools.

My husband would say my genealogical pursuit is “internalizing,” which he equates with wheel-spinning. He thinks everyone should be externalizing, thinking and doing in the real world. But there’s room for both, and I do both.

What do we really discover in our ancestors? Ourselves. I know more about myself today than I did before starting my genealogical quest. And that has to be a good thing, right?

Right!

“Mules are always boasting that their ancestors are horses.”

I read that somewhere and busted out laughing. It’s true, isn’t it? And mules aren’t the only ones who do it. I do it. You do it. We all do it.

And it’s nothing to be sheepish about either. It’s easy to understand why we light up when we find an impressive, well-known ancestor.

At its most basic, it’s because we all like a good story. Life is just a series of interconnected stories. And telling those stories is the basis of communication.

The joke, “Mules are always boasting that their ancestors are horses” is about communication. So I’ll keep my comments to the way we communicate our interest in genealogy to others.

Man o’War, one of the greatest racehorses of all time. In his career he only lost one race.

When we tell people that our ancestor is a “horse” – someone who impresses people, like George Washington or Marie Antoinette or Man O’War (see photo at right), we’ve suddenly got a conversation. We’ve made a connection.

They know just enough about that historical person to be “pre-interested.”

Conversation is about finding topics of common interest, after all, and if you don’t have anything to say except that you’re related to a person who lived a long time ago, the only response you’ll get is the back of your dinner partner’s head as he turns to talk with the person on his other side.

But talking about your “horses” isn’t all about impressing other people. In fact, it’s not even primarily about impressing other people.

My eyes glazeth over after a spell spent double-checking demographics on the umpteenth ancestor in my family tree.

If you’re at all human, you probably feel the same.

We’re like the dinner partner. We don’t want to bore ourselves. Saying you’re related to Sir Isaac Newton (as I’ve been saying since I was a child) is just a shorthand way of telling someone how interesting, how rewarding it is to research your family’s history.

But unlike our fictional dinner partner, we’re just as interested in the no-names as we are the famous ones.

I’m every bit as interested in my ancestor the Reverend John Fitch, who is not well known, as I am in Isaac Newton.

But I can’t expect anyone else to be interested in him…unless I know enough about him to weave an interesting story. I know what gets a reaction – and follow-on questions – and what doesn’t.

In fact, I’m more interested in the good Reverend Fitch, because his story is not well known. I had to work hard to find out that he moved a congregation into the wilderness of Connecticut in the mid-1600s. That he was a friend of Uncas, the chief made famous in “Last of the Mohicans,” and that he helped get Mohicans on the Colonists’ side in King Philip’s War.” That’s a story or few.

We genealogists have to be obsessed, otherwise we won’t find anything more interesting than dates and names.

We are more than kin connectors or clan catalogers, family finders, or pedigree-ophiles.

The Lone Ranger saved a wild horse from an enraged buffalo, and in gratitude the horse gives up his freedom to become the Lone Ranger’s faithful steed, Silver.

We are storytellers, and we have to be blood hounds for the details, because therein lies the story.

I’m going to keep looking for the horses in my past. I’ll no doubt find some jackasses* as well, but I bet a few of them will make interesting stories too.

Note: A mule is the offspring of a horse and a donkey, or jackass.

“Mules are always boasting that their ancestors are horses.”

I read that somewhere and busted out laughing. It’s true, isn’t it? And mules aren’t the only ones who do it. I do it. You do it. We all do it.

And it’s nothing to be sheepish about either. It’s easy to understand why we light up when we find an impressive, well-known ancestor.

At its most basic, it’s because we all like a good story. Life is just a series of interconnected stories. And telling those stories is the basis of communication.

The joke, “Mules are always boasting that their ancestors are horses” is about communication. So I’ll keep my comments to the way we communicate our interest in genealogy to others.

Man o’War, one of the greatest racehorses of all time. In his career he only lost one race.

When we tell people that our ancestor is a “horse” – someone who impresses people, like George Washington or Marie Antoinette or Man O’War (see photo at right), we’ve suddenly got a conversation. We’ve made a connection.

They know just enough about that historical person to be “pre-interested.”

Conversation is about finding topics of common interest, after all, and if you don’t have anything to say except that you’re related to a person who lived a long time ago, the only response you’ll get is the back of your dinner partner’s head as he turns to talk with the person on his other side.

But talking about your “horses” isn’t all about impressing other people. In fact, it’s not even primarily about impressing other people.

My eyes glazeth over after a spell spent double-checking demographics on the umpteenth ancestor in my family tree.

If you’re at all human, you probably feel the same.

We’re like the dinner partner. We don’t want to bore ourselves. Saying you’re related to Sir Isaac Newton (as I’ve been saying since I was a child) is just a shorthand way of telling someone how interesting, how rewarding it is to research your family’s history.

But unlike our fictional dinner partner, we’re just as interested in the no-names as we are the famous ones.

I’m every bit as interested in my ancestor the Reverend John Fitch, who is not well known, as I am in Isaac Newton.

But I can’t expect anyone else to be interested in him…unless I know enough about him to weave an interesting story. I know what gets a reaction – and follow-on questions – and what doesn’t.

In fact, I’m more interested in the good Reverend Fitch, because his story is not well known. I had to work hard to find out that he moved a congregation into the wilderness of Connecticut in the mid-1600s. That he was a friend of Uncas, the chief made famous in “Last of the Mohicans,” and that he helped get Mohicans on the Colonists’ side in King Philip’s War.” That’s a story or few.

We genealogists have to be obsessed, otherwise we won’t find anything more interesting than dates and names.

We are more than kin connectors or clan catalogers, family finders, or pedigree-ophiles.

The Lone Ranger saved a wild horse from an enraged buffalo, and in gratitude the horse gives up his freedom to become the Lone Ranger’s faithful steed, Silver.

We are storytellers, and we have to be blood hounds for the details, because therein lies the story.

I’m going to keep looking for the horses in my past. I’ll no doubt find some jackasses* as well, but I bet a few of them will make interesting stories too.

Note: A mule is the offspring of a horse and a donkey, or jackass.

First names, like eye color, tend to run in families.

In my (ex) brother-in-law’s family, every first son is James, every second son is John. It has been like that for generations. He broke the tradition by a hair, naming his first son John. James will have to wait for esteemed son number two.

My sister tossed on our own family naming tradition by adding a middle name for baby John that is old-fashioned and multi-syllabic: Chauncey, which is the name of our great-great grandfather.

Chauncey is also a name that is typical for my family. Given names for us tend to be a mouthful: Theodore. Cynthia. Thaddeus. Justine. Florence. Priscilla. Abigail. Frances.

In all 2,101 ancestors I’ve come up with so far, our most common female name is Mary. There are 112 of them, which still leaves 1,989 who are not named Mary. That makes for a lot of unique names.

Of course, each generation seeks its own naming trends,whether we’re talking the 1980s or the 1480s.

Every one of my 16 Abigails are from the 16- and 1700s, except one 1800s.

Sometimes these generational naming trends fight family traditions for naming supremacy.

And so somewhere right now 2014’s trending “Joshua” is bumping a favorite family name off the birth certificate. Just as the name “Ashley” did a few years ago.

And the way “Ruth” spiked from 66th to fifth most popular girl’s name after the birth of the hauntingly beautiful “Baby Ruth,” daughter of President Grover Cleveland, in 1891.

But does every family have names as odd as mine?

Look through my ancestors and you’ll find Aleonore, Amabil, Ansfred, Apollonia, Apollos, Augustine, and Avelina. And Benoni, Beriah, Biggett, Bishop, and Bran. That doesn’t even exhaust odd names from the A’s and B’s!

Of course, they probably weren’t odd for the time, and that’s where it helps to put on your best Sherlock Holmes deerstalker hat and play Ancestral Name Detective.

Of course, they probably weren’t odd for the time, and that’s where it helps to put on your best Sherlock Holmes deerstalker hat and play Ancestral Name Detective.

You can sometimes guess in what era an ancestor was born, or the circumstances of an ancestor’s birth, just by the their name.

My eighth great grandfather was Benoni Gardiner. That odd name is a clue that his mother might have died in childbirth, which she probably did, as her year of death is also his birth year.

It didn’t take me much Googling to find that Benoni is a name that had special meaning in early New England families. It comes from a passage in Genesis on the death of Rachel, wife of Jacob:

And it came to pass, as her soul was in departing, (for she died) that she called his name Benoni: but his father called him Benjamin.

It’s no trick at all to know that my ancestors, Silence Brown, Delight Kent, Mindwell Osborne, Temperance Stewart, and Thankful Clapp were all named in the trendy Puritan practice of choosing virtues as children’s names.

It’s no trick at all to know that my ancestors, Silence Brown, Delight Kent, Mindwell Osborne, Temperance Stewart, and Thankful Clapp were all named in the trendy Puritan practice of choosing virtues as children’s names.

And with a name like Henry de Pomeroy, you can bet my 21st great grandfather lived in 11th or 12th century England, which he did.

But I admit I was thrown by my 18th great grandmother, Ethel May Dyer, who was born in 1320 England, not the early 20th century American Midwest.

You can learn a lot about history, too, when researching ancestral names.

Walter Giffard, my 23th great grandfather, was born in 1040 in Normandy. I figured he must have palled around with William the Conqueror, because next we see him he’s been installed as Earl of Buckingham after William won the Battle of Hastings in 1066 and parked his throne in England.

Sure enough, a little Googling proved my hunch was right. (Don’t be too impressed. The Battle of Hastings in 1066 is one of the few historical dates I remember from school.)

At first ol’ Norman-named Walter was surrounded by people with weird Anglo-Saxon names like Cyneweard, and his friends Godric, Aelfwine, Godgivu , Aethelred, and Deorwine.

William and his Norman crowd brought their refined, wine-drinking names with them, and the not-so-sore-losing conquerees soon discovered that they liked both the culture and the names of the conquorers better.

That’s why your neighbors are probably William instead of Wigberht, John instead of Eoforhild, or Susan instead of Swidhun.

It’s also the reason there are, statistically, 60 Michaels to every Hector, and 57 Johns to every Stuart.

Because the pool of popular children’s names shrank after the Norman invasion.

Instead of the Anglo-Saxon baby name book that would have been hundreds of pages long, parents would have had more of a pamphlet to go through now.

To put it another way, if you went out to meet a group of ten friends in England in about 1300, the group would have, statistically, two Johns, two Matildas, at least one William and Isabella, and either a Thomas, Bartholomew, Cecilia, or Catherine for the others.

Naming became so uncreative in England, in fact, that there were sometimes several children with the same names in one family.

Like a family noted in the History of Parish Registers, which reads:

Like a family noted in the History of Parish Registers, which reads:

“One John Barker had three sons named John Barker, and two daughters named Margaret Barker.”

I just hope they didn’t all look alike too.

It got confusing real fast. Thus the surname became a thing.

For a while, last names kept to the knitting. If you read King Edward IV’s accounting books from 1480, you would see IOUs made out to:

John Poyntmaker, for pointing of xl. Dozen points of silk pointed with agelettes of laton.

To a laborer called Rychard Gardyner working in the gardyne.

To Alice Shapster for making and washing xxiiii. Sherts, and xxiiii. Stomachers.

But they started running into a problem of duplicates, so someone got smart and extended the roster of names by adding “son” (in whatever appropriate language) to the ends of given names.

Then someone else started in on adjectives, like Short, Little, Red, or White.

Then someone else started in on adjectives, like Short, Little, Red, or White.

Then they started putting their creative muscle into it and got Longfellow, Blackbeard, Stern, and Peacock (“vanity, vanity, all is vanity”).

You probably don’t know anyone named “Crooked Nose,” but maybe you know a Cameron, which is Gaelic for the same.

And you probably don’t know an “Ugly Head,” but I bet you know its Gaelic version, Kennedy.

You probably do know what the name Williamson means. But I bet you didn’t know that William is German for Desire Helmet.

It’s fun to play ancestral name detective, though it can be frustrating. But if you’re hitting brick walls that you need to find a way around, put on your deerstalker hat and think like Sherlock. You might be surprised at how well it works.