I’ve never embraced my Scotch-Irish ancestry.

In the first place, my mother always emphasized that the word is “Scots,” not “Scotch.” I’m pretty sure it’s because she disliked Scotch’s association with whiskey. And she never hyphenated “Scots” with the “Irish” part. To her, our ancestors were purely Scottish, and the fact that they passed through Ireland for a generation or two was of negligible consequence. Irish meant Catholic to Presbyterian her, and we assuredly were not Catholic, thank you very much, and here you can see where comes all the trouble in the Isles of England.

sure it’s because she disliked Scotch’s association with whiskey. And she never hyphenated “Scots” with the “Irish” part. To her, our ancestors were purely Scottish, and the fact that they passed through Ireland for a generation or two was of negligible consequence. Irish meant Catholic to Presbyterian her, and we assuredly were not Catholic, thank you very much, and here you can see where comes all the trouble in the Isles of England.

But the main reason I never embraced the Scots-Irish is because any time that designation is mentioned it seems to be preceded by “The Fighting.” I don’t find that embraceable. A certain segment of Scots-Irish Americans, led lately by former Secretary of the Navy, Jim Webb, likes to proudly point to the Scots-Irish propensity to, as he says, mistrust government and bear and use arms.  He even wrote a book called, “Born Fighting: How the Scots-Irish Shaped America.”

He even wrote a book called, “Born Fighting: How the Scots-Irish Shaped America.”

If the Scots-Irish are so damn testy, where are all of Scotland’s wars? Huh?

Webb and his cohorts say the Scots-Irish have “a propensity” to mistrust government and bear and use arms. All “a propensity” means is “a prejudice.” A propensity to mistrust means that however a person decides to act, the decision is already weighted toward mistrust; the deck is stacked against trust. Completely objective people do not have “a propensity” to believe a certain way, no matter what the evidence says.

Now, don’t go all political on me. There’s no political subtext meant here. Honestly, if Webb and others are right, I’m glad the Scots-Irish were around to save our butts in the Revolutionary War. (But then, if three quarters of the Rebel Army was Scots-Irish, as he points out, how do you explain the South losing the Civil War? …Just askin’.)

Now, don’t go all political on me. There’s no political subtext meant here. Honestly, if Webb and others are right, I’m glad the Scots-Irish were around to save our butts in the Revolutionary War. (But then, if three quarters of the Rebel Army was Scots-Irish, as he points out, how do you explain the South losing the Civil War? …Just askin’.)

You know, it takes (at least) two sides to make a war. Nearly all Scotland’s wars were fought with the English, but we don’t go around calling them, “The Fighting English,” do we?

A little background might help here.

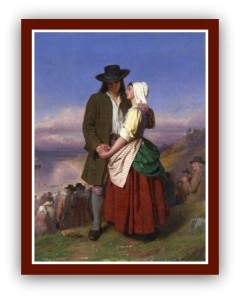

When the Scottish people began their several hundred year migration to America, they had just spent 700 years battling the English. No kidding. 700 years! Finally, in the early 1700s, Scotland’s James I became king and unified Great Britain. James decided to stock Ireland with Protestants from Scotland, and the Scots were only too happy to oblige because they were just coming out of a decade-long famine and hoped for better lives elsewhere. Their new lands were in Northern Ireland, where they were immediately seen as the enemy by the Catholics opposed to their religion and infringement on Ireland’s lands.

When the Scottish people began their several hundred year migration to America, they had just spent 700 years battling the English. No kidding. 700 years! Finally, in the early 1700s, Scotland’s James I became king and unified Great Britain. James decided to stock Ireland with Protestants from Scotland, and the Scots were only too happy to oblige because they were just coming out of a decade-long famine and hoped for better lives elsewhere. Their new lands were in Northern Ireland, where they were immediately seen as the enemy by the Catholics opposed to their religion and infringement on Ireland’s lands.

So far we’ve tallied 700 years of war, a ten-year famine, and now 150 or so years of strife within Northern Ireland. But there’s more.

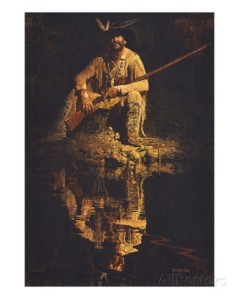

The American Colonies were prospering, but they had problems with the Natives. (And the Natives had problems with them!) Natives kept attacking the towns and settlements, and the situation was particularly bad in those parts of the Colonies that bordered the frontier. So the secretary of state of Pennsylvania thought up a clever solution. He would create a human buffer between his colony’s towns and the frontier. And who better to be border buffers than the fighting Scots-Irish. So he offered free land to lure immigrants, who were already eager to get out of Ireland.

The American Colonies were prospering, but they had problems with the Natives. (And the Natives had problems with them!) Natives kept attacking the towns and settlements, and the situation was particularly bad in those parts of the Colonies that bordered the frontier. So the secretary of state of Pennsylvania thought up a clever solution. He would create a human buffer between his colony’s towns and the frontier. And who better to be border buffers than the fighting Scots-Irish. So he offered free land to lure immigrants, who were already eager to get out of Ireland.

Those poor Scots-Irish. An entire people suffering from “soldier’s heart,” a sort of constant anxiety first described in Civil War veterans. They couldn’t catch a break.

People become conditioned to their environments. Said a different way, your environment can make you a different person. If they had just come out of 860 years of peace instead of war, maybe Jim Webb’s book would be called “The Peace-Loving Scots-Irish.”

My mother’s mostly-Scottish family is rural Virginia, though by what evidence I’ve seen so far they came by way of Jamestown, not by the well-traveled Scots-Irish route via Pennsylvania and down through the Ohio Valley. The character of my mother’s family is gentle, communal, earthy, peace-loving, home-loving, and not particularly religious or political.

My mother’s mostly-Scottish family is rural Virginia, though by what evidence I’ve seen so far they came by way of Jamestown, not by the well-traveled Scots-Irish route via Pennsylvania and down through the Ohio Valley. The character of my mother’s family is gentle, communal, earthy, peace-loving, home-loving, and not particularly religious or political.

Since getting interested in genealogy I’ve come to better embrace my one quarter Scots-Irishness. I can move beyond media-friendly monikers like “Born Fighting.”  I can see now that it’s not about the fighting. It’s about the courage. They didn’t move into Ireland to fight. They didn’t sail to America to fight.

I can see now that it’s not about the fighting. It’s about the courage. They didn’t move into Ireland to fight. They didn’t sail to America to fight.

Labels like “The Fighting Scots-Irish” emphasize a certain kind of courage at the expense of other kinds. Like the courage to cross a border, even a sea, to better their lives. Like the courage to walk into the wilderness and carve out a place to call their own. That doesn’t take aggression. They didn’t move forward by way of slaughter or hacking down forests. They moved forward by facing the unknown with a powerful strength of character and purpose. To carve a place in the wilderness and make it their own, after being chased around and out of for a couple centuries. “Leave us be!” could have been their moniker.

Leave us be! To live our lives in peace and community, we’ve crossed the Irish Sea, and then the Atlantic Ocean. We were lured by King James, who planted us as Presbyterian seeds in Ireland, and then by American colonists who sent us to the hinterlands and planted us a buffer between them and the Natives. Conflict precedes us, it does not follow us. You think us fighters, but we are not. Leave us in peace and we stay in peace!

Now here we are further cementing the fate of these people by popularizing the fighting image, lauding them as heroes for sending their boys to fight our shared wars. This doesn’t mean we shouldn’t be proud of them, because we should. But we shouldn’t make it seem expected of them because they’ve got fighting in their blood and that’s always been their role.

Now here we are further cementing the fate of these people by popularizing the fighting image, lauding them as heroes for sending their boys to fight our shared wars. This doesn’t mean we shouldn’t be proud of them, because we should. But we shouldn’t make it seem expected of them because they’ve got fighting in their blood and that’s always been their role.

I’m embracing the one quarter of my blood that is Scots-Irish. These are most assuredly people of strength and courage, and I like that. Of course, there’s also the music, but that’s another story for another time.

May the best ye’ve ever seen

Be the warst ye’ll ever see.

May the moose ne’er lea’ yer aumrie

Wi’ a tear-drap in his e’e.

May ye aye keep hail an’ hertie

Till ye’re auld eneuch tae dee.

May ye aye be jist as happy

As we wiss ye noo tae be.