You can see Chapter 1 of this story here.

FRANCIS EGGLESTON: CHAPTER 2

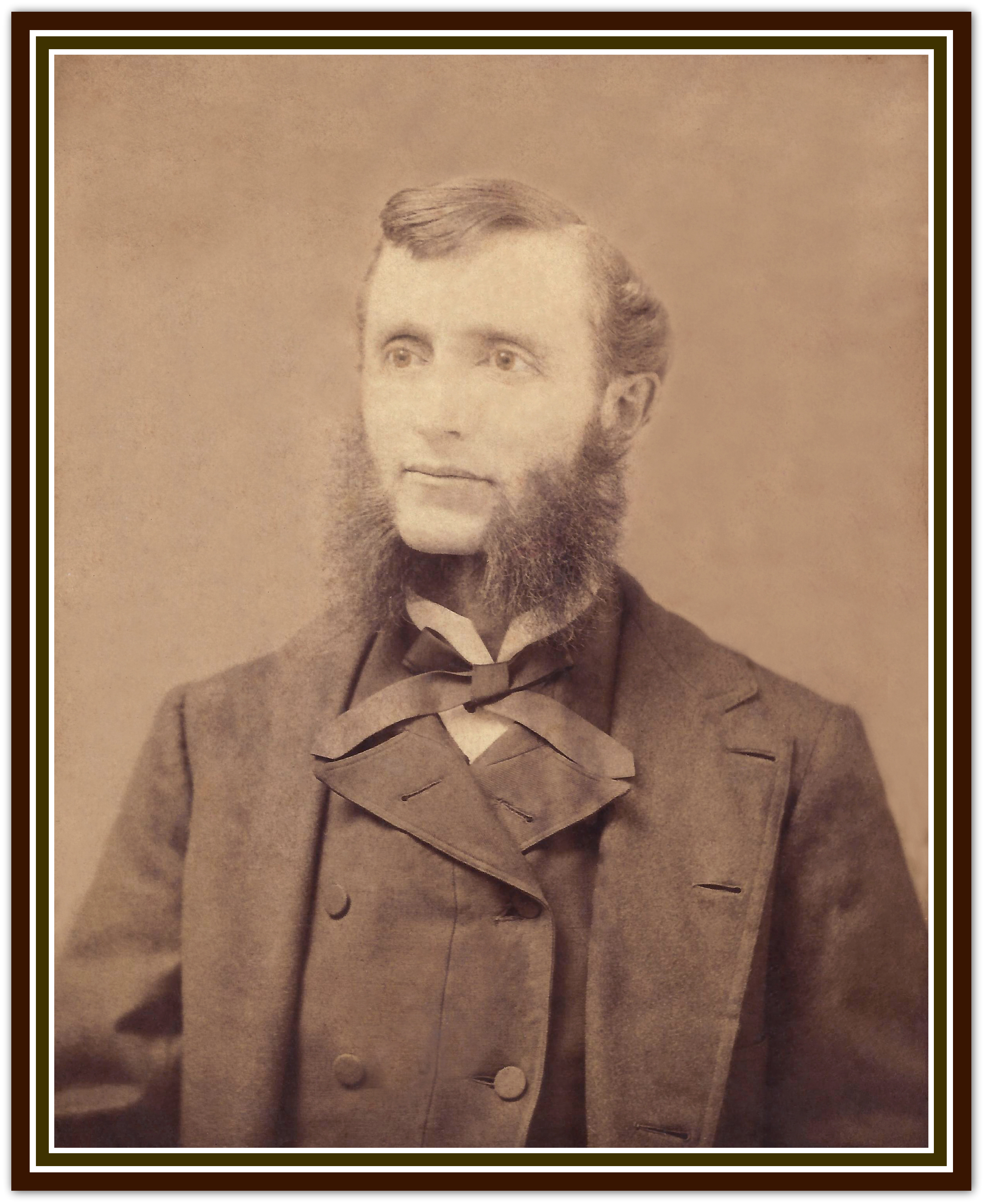

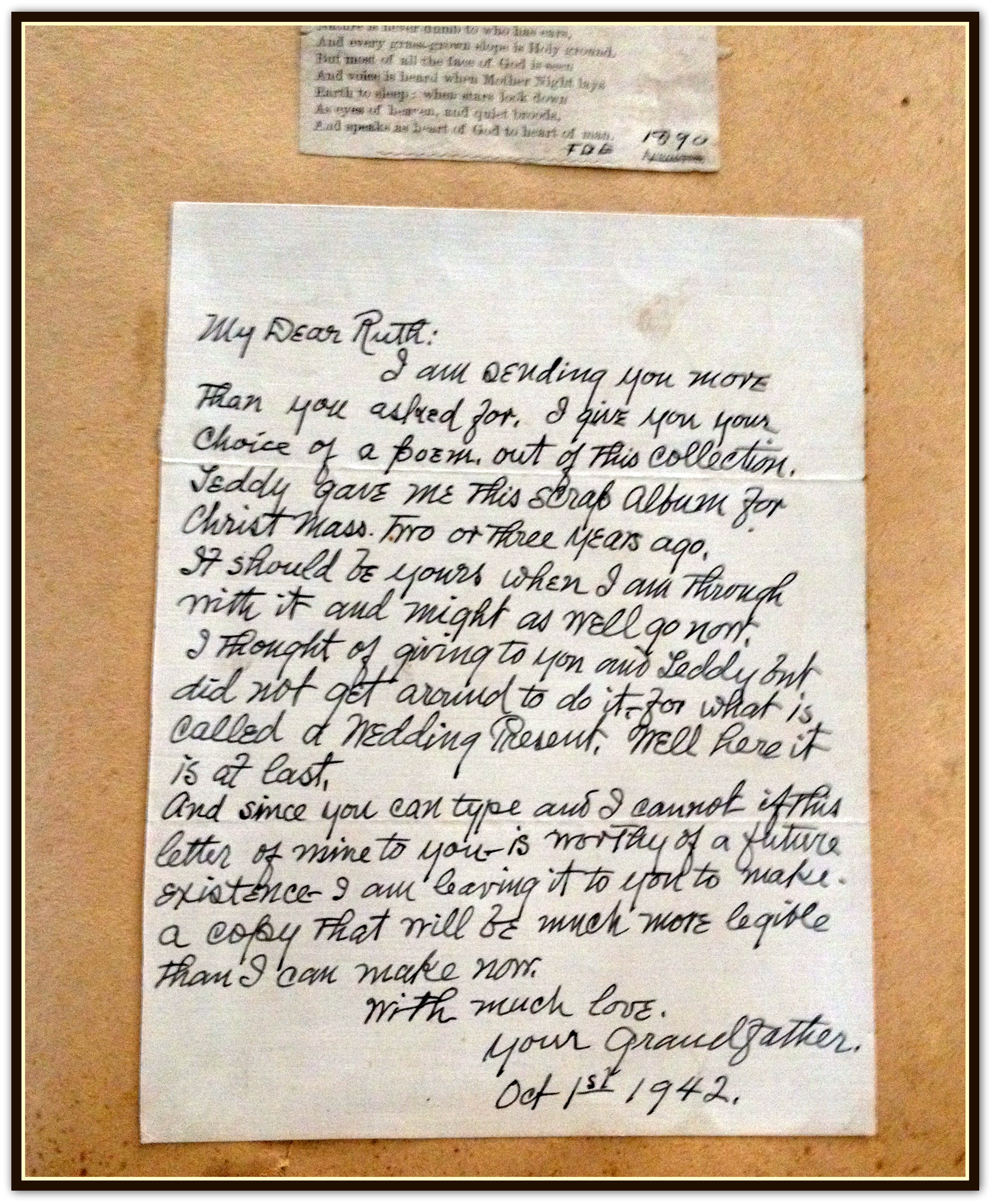

Francis Otto Eggleston, my great-grandfather, was a medical doctor first, then a Methodist minister, a Unitarian minister, and finally, in his later years, newspaper columnist.

But he didn’t consider himself a Renaissance man. He thought of himself instead as a man who made many poor choices before settling down to do something he loved.

Francis was a poor fit with his environment right from the start.

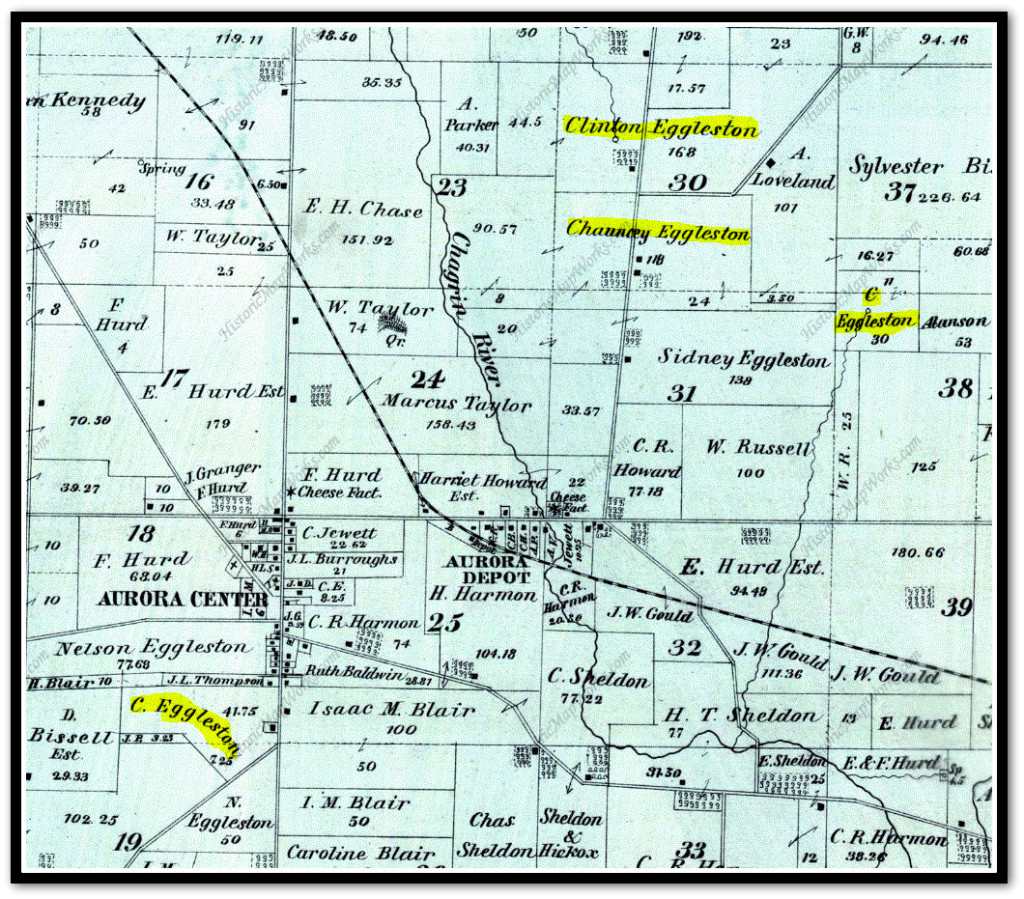

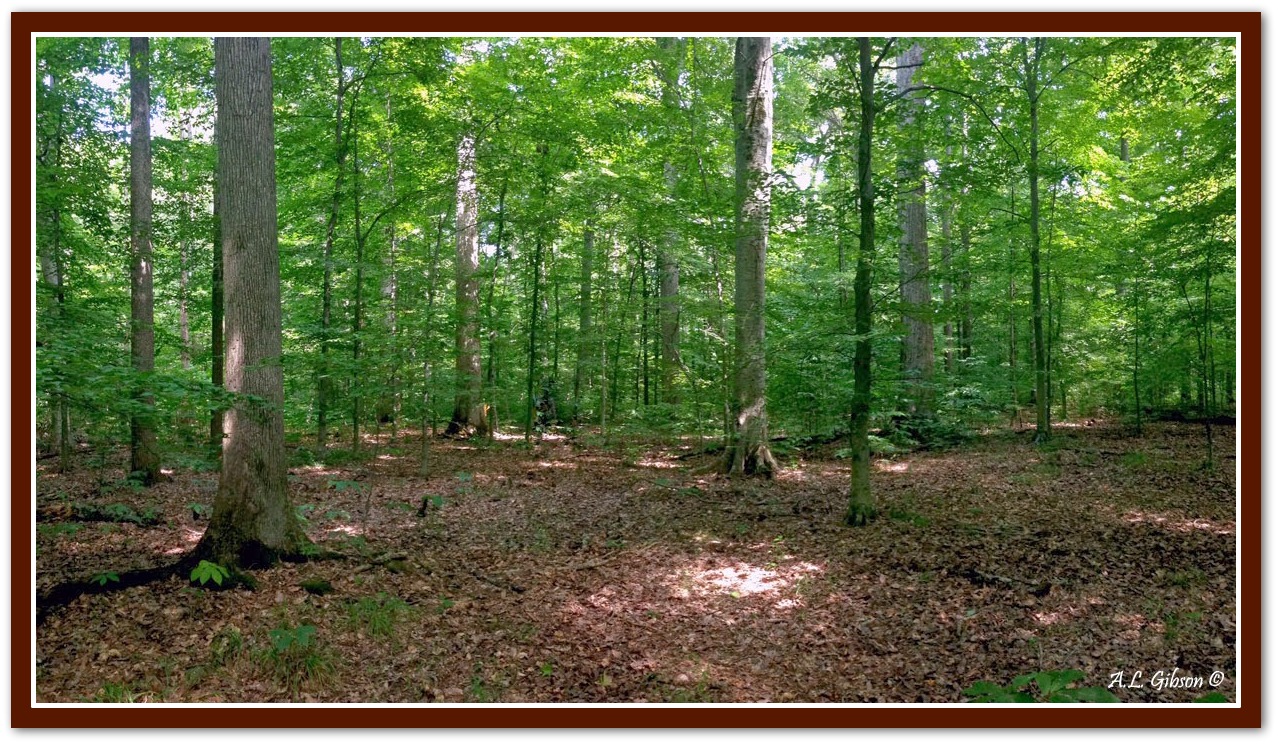

In his biography he writes that he was born, “in a new house on a farm in Aurora,” an Ohio  village founded by his forebears, who walked with their wagons hauled by teams of oxen from Connecticut across the rugged, nearly impenetrable Allegheny mountains and into the wild frontier of New Connecticut, as the Ohio territory was called, in 1807.

village founded by his forebears, who walked with their wagons hauled by teams of oxen from Connecticut across the rugged, nearly impenetrable Allegheny mountains and into the wild frontier of New Connecticut, as the Ohio territory was called, in 1807.

There they settled, “25 miles south east of the village of Cleveland,” which was no more than “a biggish village” even as late as 1853, the year he, Francis Eggleston, was born.

From a population of less than 50,000 in 1803, which was about one person per five miles square, the population of Ohio grew to about two million in just the 50 years between when the Eggleston settlers arrived and Francis Eggleston’s birth.

Small towns dotted the landscape, and farms stretched their borders to the edge of wilderness. It was a good time – an exciting time – to be in Ohio, with all its promise as a new state in a new country.

Small towns dotted the landscape, and farms stretched their borders to the edge of wilderness. It was a good time – an exciting time – to be in Ohio, with all its promise as a new state in a new country.

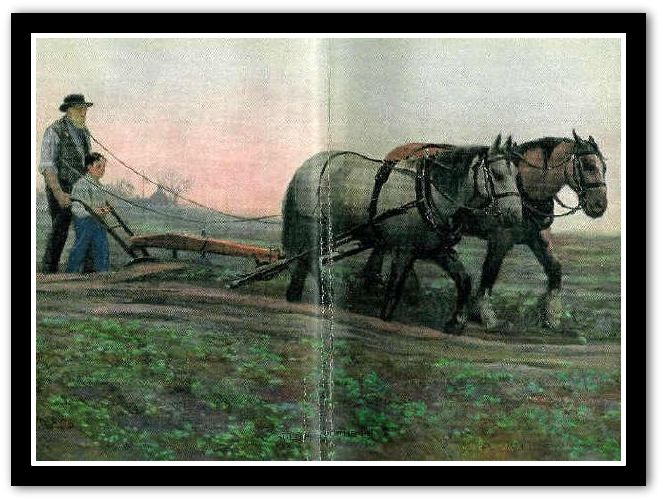

The mid-1800s was a time of great invention for farm machinery, too. In 1830, using the most modern equipment of the day, a farmer could expect to spend about 300 hours to produce 100 bushels of wheat. Just 20 years later, by the time Francis was born, with the invention of reapers, steel plows, thrashing and mowing machines and improved fertilizers, that time would be cut to a third, about 90 hours.

But Clinton Eggleston, Francis’s father, did not go in for modern farm machinery, and it was plenty vexing to Francis.

I don’t know Clinton’s reasons. Francis wrote simply that his father was “conservative in methods.”

I don’t know Clinton’s reasons. Francis wrote simply that his father was “conservative in methods.”

He could well afford what machinery he wanted, as he was a prosperous dairy farmer and sugar producer.

Perhaps one who is conservative in his ways simply has a romantic attachment to the old ways, enjoying a slower, quieter way of life.

Of course, it took a while for the new machinery to become widely used. The machines had to first be manufactured in quantity, and then marketed far and wide, reaching out to these “hinterlands” farmers. So Francis had to wait.

He wryly compares the era of his youth to the age when man first discovered tools, the Neolithic era, writing of his childhood, “That was back in the tool age — when a plow, harrow and one horse cultivator ridden by a boy and guided by a man” did the work.

“The machine came in about the time that kerosene (coal oil then), put the tallow candle out of business, which must have been around 1860.

Ironically, as much as Francis wished he had the advantages of modern machinery as a lad on the farm in 1870, he would change his mind by 1941, wishing for the days of horse and buggy again, because cars go too fast!

Still, you can sense his frustration with farm life when he writes,”We had a farm of something over 200 acres…. “What we did not have was labor saving machines — we always did the hard work the hard way. This did not tend to make boys like the farm.”

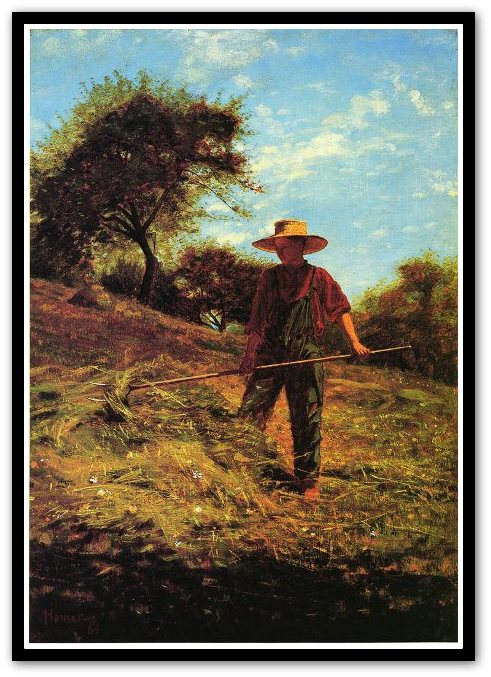

He lived the typical farm boy’s life, milking cows, feeding chickens, and guiding the big work horse down field rows while his father drove the plow, which was a good deal of work on a 200+ acre farm.

Though he was a scant 120 pounds and called himself more of “a dreamer” than the kind of boy who would thrive on farm work, he was expected to pull his weight.

Just an adolescent, he was sent to split timber into “rails, 12 feet long and perhaps five inches square,” and to put his muscle behind “a great wood pile which was cut by horse-power and drag saw and split and corded by man and boy power.”

Just an adolescent, he was sent to split timber into “rails, 12 feet long and perhaps five inches square,” and to put his muscle behind “a great wood pile which was cut by horse-power and drag saw and split and corded by man and boy power.”

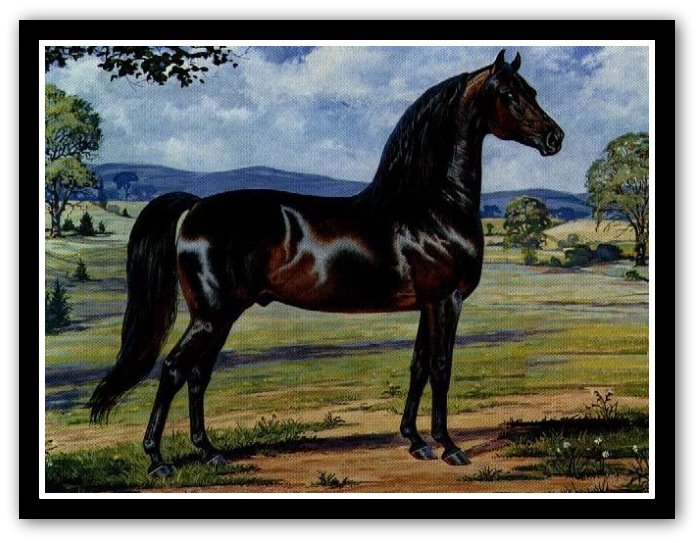

What he did like, though, were the horses. The family “always had three or more horses or some extra colts growing up and sometimes a yoke of oxen.

“I was fond of ‘horse-flesh’ and ‘broke’ one colt to drive before he was a year old. He would pull me on a hand-sled and keep up with a full grown team.

“In summer I rigged up a sulky and drove him until he was full grown.”

In his biography he tells the story of his father’s “gorgeously trimmed” Rockaway canopy-top carriage.

The Rockaway was a luxury model carriage, with a fully enclosed cabin, brass carriage lamps, beveled windows, or “glass curtains,” tufted leather seats, and spring axle for a smoother ride. That was quite the ride for a small Ohio farm town!

“I never knew where he got it but it lasted until a pair of colts ran away with it, broke the pole and smashed the top.

“My mother jumped out but one horse had simply landed on top of the other – being scared by a noisy rattling rig for hauling empty barrels – when the pole broke Father had to let them go until someone caught them.

“He sold them then – never drove them again. That was about 1860 as I remember. After this we had a splendid little team of dark brown Morgans – and after this I was not so familiar with the teams, but Father had good horses.”

Francis helped produce all the chief products of the farm, which were milk, butter, cheese, and sugar; and to sow, grow, hoe, and harvest the field crops, which were hay and corn to feed the cows, and oats for the horses.

Francis helped produce all the chief products of the farm, which were milk, butter, cheese, and sugar; and to sow, grow, hoe, and harvest the field crops, which were hay and corn to feed the cows, and oats for the horses.

The cows “ran out on pasture in summer, eating grass, and were driven in by a boy and dog morning and eve.”

This was a job he no doubt liked, though, as it gave him time to think on the ideas he read about from his “bedside books” the previous night before falling asleep, and to practice the poetry he memorized so well and quoted throughout his life.

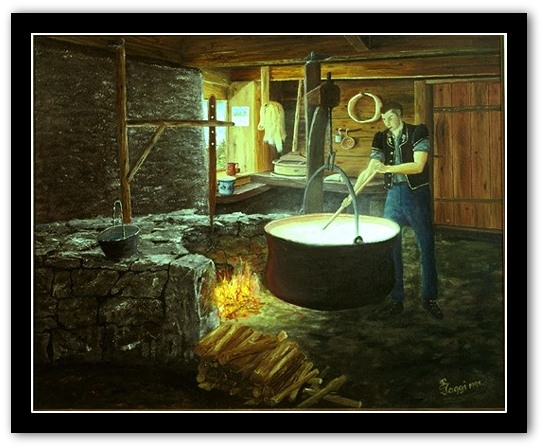

The family’s chief occupation was dairy farming. After milking the cows, the new milk was set in tin pans that held about eight quarts each and were left to set until the cream rose to the top, which took about 24 hours. Then the cream was skimmed off with a perforated tin skimmer and used to make butter, and a small bit used in cooking.

He described the cheese making process:

“The milk in early time was heated with a steamer and worked dry in a big wooden tub. Later there was a regular cheese vat,” and “cheese was pressed in a hoop by its own weight.

“After the war (1860-64) milk was sold to cheese factories and this made less work for the housewife. Washing milk pans, pails and a churn was work, and called for plenty of hot water.

“When the factory system came in milk was strained into a tin can as large as a barrel and loaded on a wagon that had a route.”

From our perspective in 2014, all this sound like a huge amount of work, doesn’t it? Most of us in America have moved over to the “knowledge economy,” and have turned over raising our food, building our homes, and just about everything physical to others.

That’s just not how it was in the second half of the 19th century, when most of America did not live in cities.

I began this story saying that Francis Eggleston often found himself in the wrong place, doing the wrong thing, or more specifically, the wrong thing for his temperament and interests.

I began this story saying that Francis Eggleston often found himself in the wrong place, doing the wrong thing, or more specifically, the wrong thing for his temperament and interests.

Was being born and raised on a farm one of his experiences of poor fit? He seems to think so, though never says.

“As a boy,” he wrote, “I was said to be lazy. The true fact was that I was always averse to farm drudgery and dirt. I was mechanical, and always had something to make or repair – lazy I was not.”

Francis Eggleston didn’t find his identity in outdoor labor, but in his mind. The next stage of his life would fit him much better. We’ll see that when next we pick up his story in Chapter 3, here.

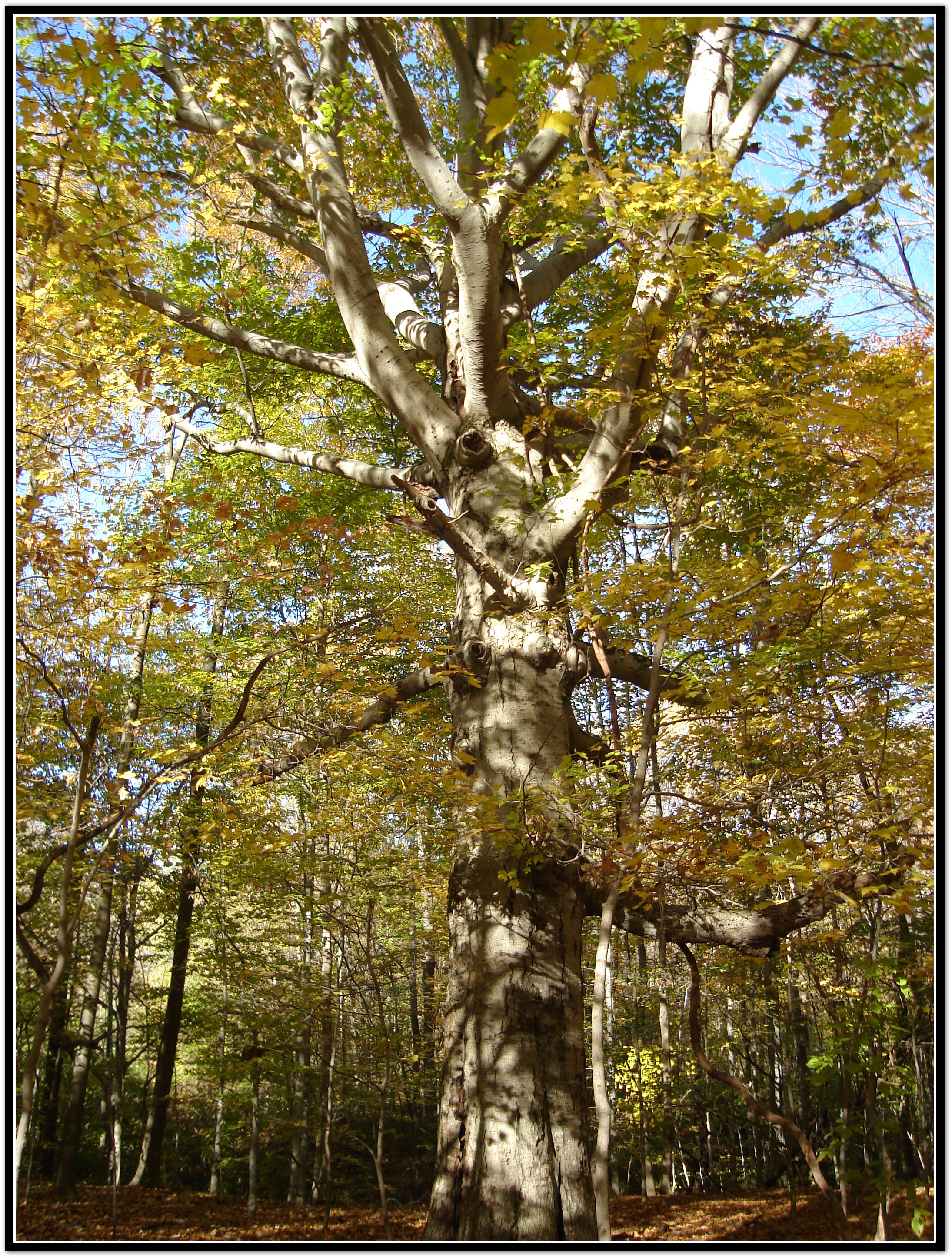

There were no chestnut trees, but they had hickory trees so big around that a full-grown man could not wrap his arms around them.

There were no chestnut trees, but they had hickory trees so big around that a full-grown man could not wrap his arms around them.

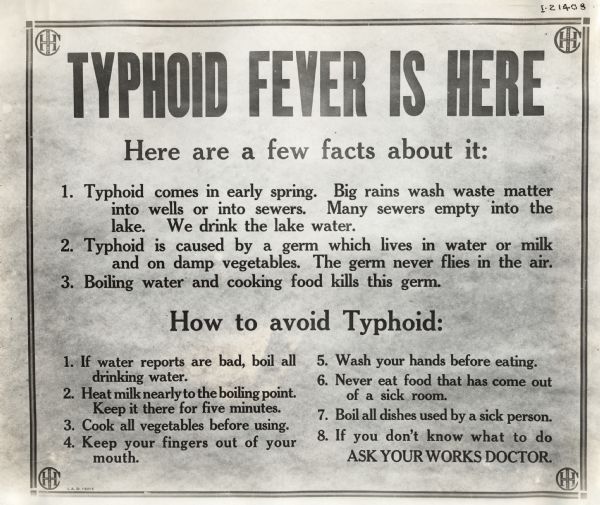

Recovery for the others was complete, and my great-grandfather suffered no long-lasting ill effects from the disease, other than the tragic loss of mother and sister, who I am sure he mourned for all his life.

Recovery for the others was complete, and my great-grandfather suffered no long-lasting ill effects from the disease, other than the tragic loss of mother and sister, who I am sure he mourned for all his life.