When Pearl Abigail Eggleston stepped out her front door and into the dusty, packed-dirt streets of 1900’s Chagrin Falls, Ohio, she wore white lace. Like a swan, she glided across Summit Avenue, delicately lifting the hem of her skirts just an inch and lengthening her stride to clear wheel ruts, revealing only the toes of her kid leather lace-up ankle boots, polished that morning. Her blouse, gloves, and skirts were all white as a swan’s wing, and her fine, blonde hair upswept beneath a pale green feathered hat. Embroidered vines and leaves circled her high-necked collar, and pearl buttons fastened her blouse and sleeves. No dust settled on her hem. No smudge fell upon her cuff. She glided as if over water, not dirt and gravel.

Or at least this is how I imagine her, navigating the world on her terms and doing her best to make it look effortless. That characteristic was to be tested many times in her life.

She was born in 1879 to a medical doctor and college-educated mother, an only child for 11 years until her younger brother, Paul, was born. This gave her mother, Clara Brown Eggleston, ample time to raise Pearl with all the advantages afforded a child of polite society.

Pearl did not come from a wealthy family. She was not born with a silver spoon in her mouth, though her mother no doubt found the money for one.

Even as a girl Pearl enjoyed nice clothes and good manners, a trait she shared with her mother. They were not social climbers, they were merely bred and trained in the fashion of 19th century ladies. “Pearl could do without the necessities of life as long as she has the luxuries,” her father once said.

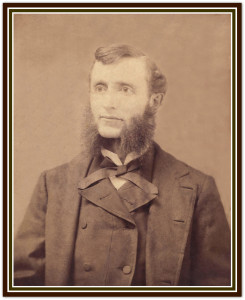

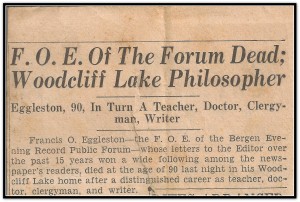

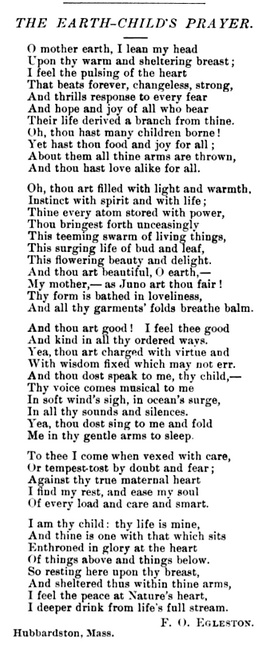

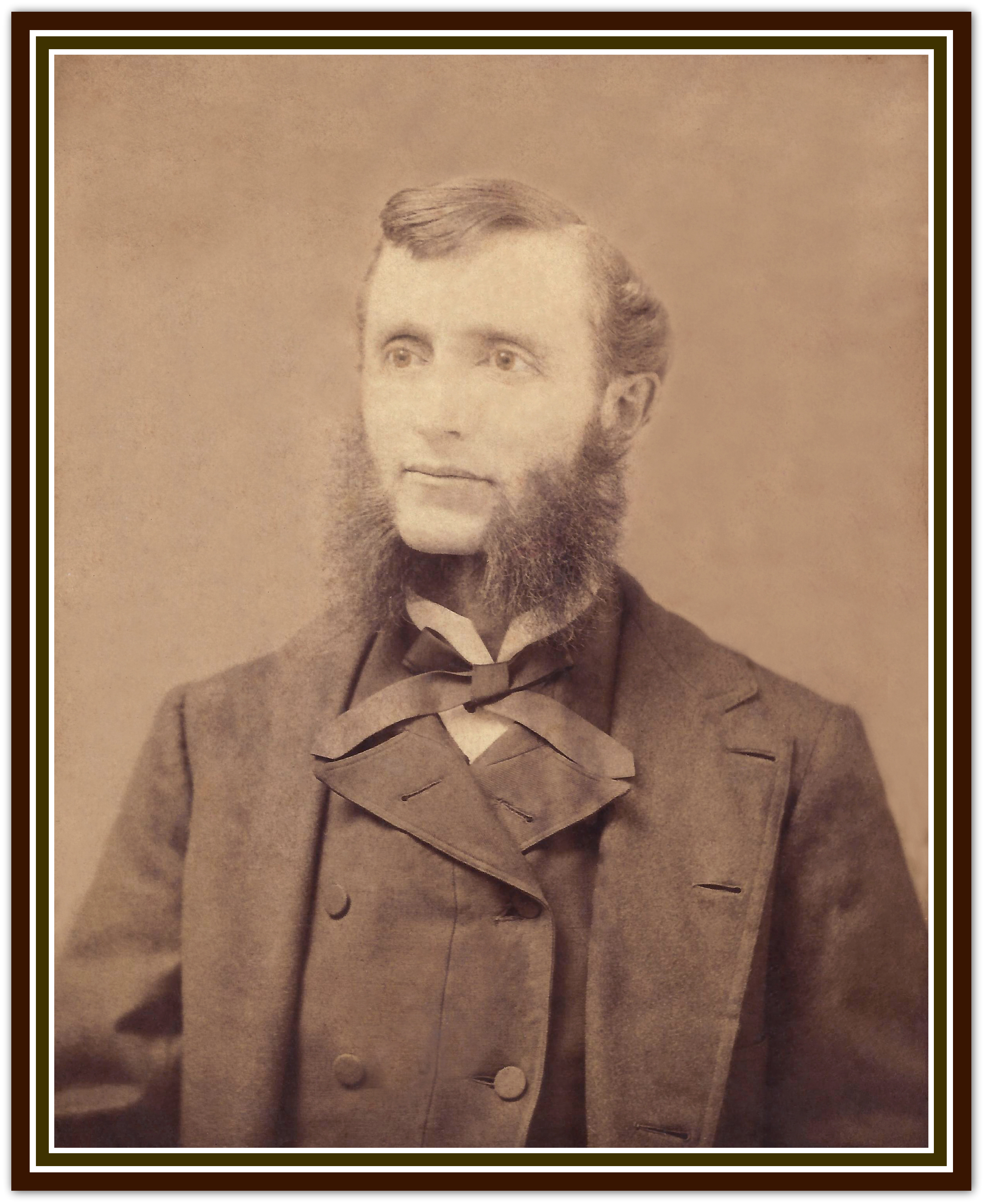

Pearl’s father, Francis Otto Eggleston, was a commanding presence. He was an eloquent speaker who had studied the classics from a young age, and he could hold an audience. That, along with his position as a physician of Knoxville, Tennessee, placed the young Eggleston family in that town’s best society, where little Pearl would watch and learn behaviors and manners she held to her whole life, whether living in Manhattan, or in the dust bowl poverty of wild Oklahoma.

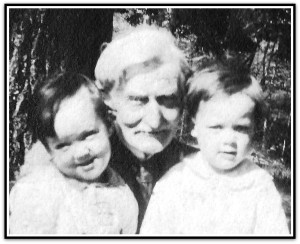

In his biography, her father wrote of baby Pearl: “She was a picture. She was the only living wax doll I ever saw, and everyone admired her.” I have a photo of her at about age five or so, a delicate white lace collar buttoned high on her neck over a wool coat, her hair pulled back tight and with a curl “just so” on either side of her forehead. She looks like a serious little girl, her cupid’s bow lips and her heavy-lidded teardrop eyes both downturned at the outer points.

This is not a child who has ants in her pants. She is not barely contained, as are many children her age in their photos. She looks, instead, like she would be content to sit in this place until her mother tells her she can move, whether that is in one minute or ten.

This is not a child who has ants in her pants. She is not barely contained, as are many children her age in their photos. She looks, instead, like she would be content to sit in this place until her mother tells her she can move, whether that is in one minute or ten.

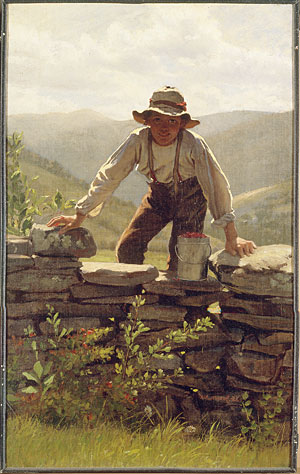

Her father remembered the stylish outfits her mother put together with apparent pleasure. “Pearl must have been around six or seven years of age when we made our trip to and sojourn in Boston. I recall her fuzzy coat of dark green, and the red turban with an eagle’s quill stuck slantingly in one side. (A very picturesque headpiece.) She had her blond hair cut off before we left Troy, as did all her little friends of the same age.”

That haircut, and one of her similarly-shorn friends, were immortalized in a photo soon after.

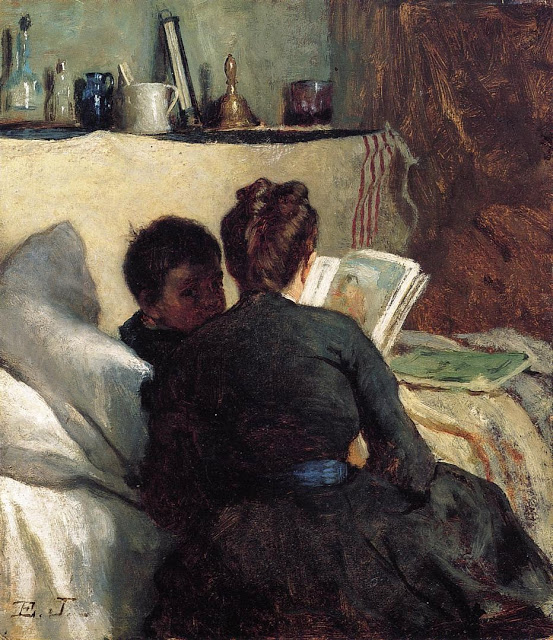

In white eyelet and lace, Pearl gazes serenely into the distance over her friend, whose head rests lightly on Pearl’s shoulder. Grandmother, for Pearl Abigail Eggleston was to be my grandmother, has that same calm look as in the previous photograph, but behind that look lay what her daughter-in-law, my mother, called “a tender heart” that expressed both joys and sorrows to great degree.

Pearl’s father, by that time, had made the switch fro m healing people’s bodies to healing their souls. “I tire of butchery as an occupation,” he wrote. He too, had a tender heart. And so he returned to school for a Doctor of Divinity degree, emerging a Methodist minister.

m healing people’s bodies to healing their souls. “I tire of butchery as an occupation,” he wrote. He too, had a tender heart. And so he returned to school for a Doctor of Divinity degree, emerging a Methodist minister.

From that point on the family moved frequently, as an itinerant clergy is one of the practices of Methodists, and has been since the church’s beginnings, when John Westley wandered the English countryside, preaching out of doors and from town to town.

Like other Methodist clergy, when the Egglestons moved, it was not just to the other side of town. They went from Ohio to Tennessee, to Vermont, to Massachusetts, New Jersey, New York, and back to Ohio. Pearl and her mother were dutiful, Clara taking her place in church society and Pearl in school as soon as they landed in a town.

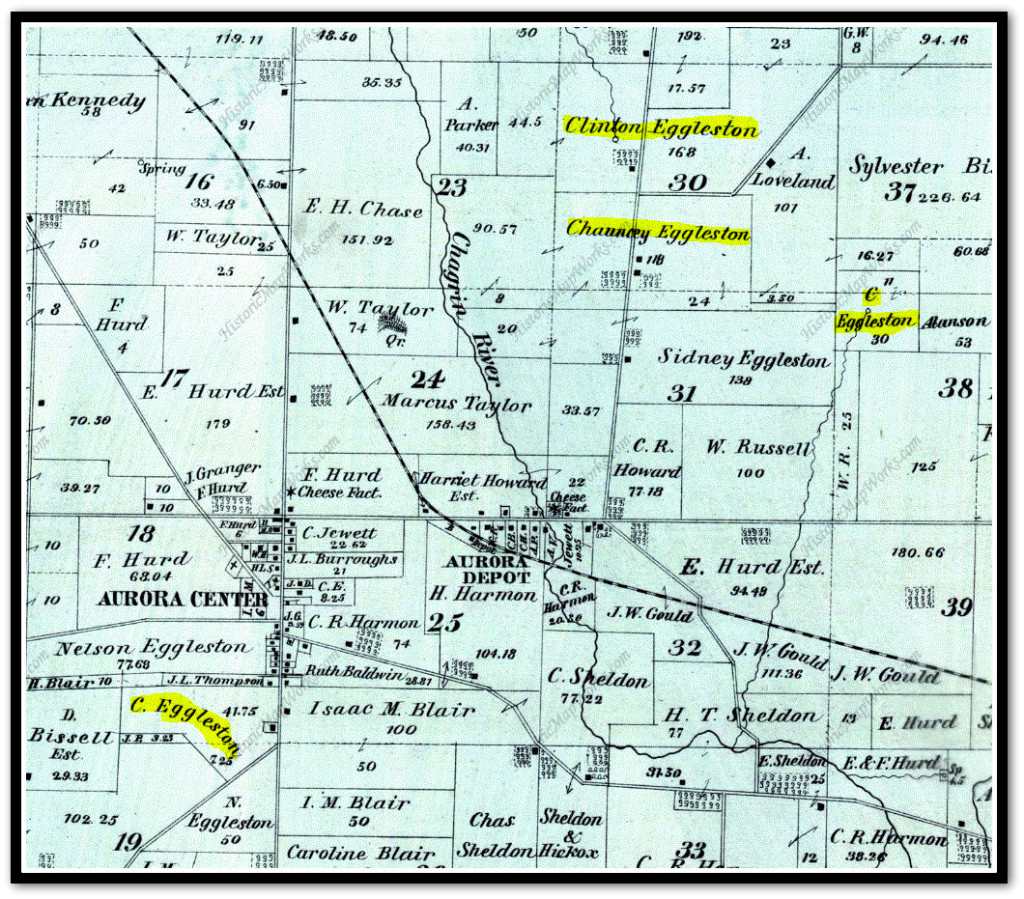

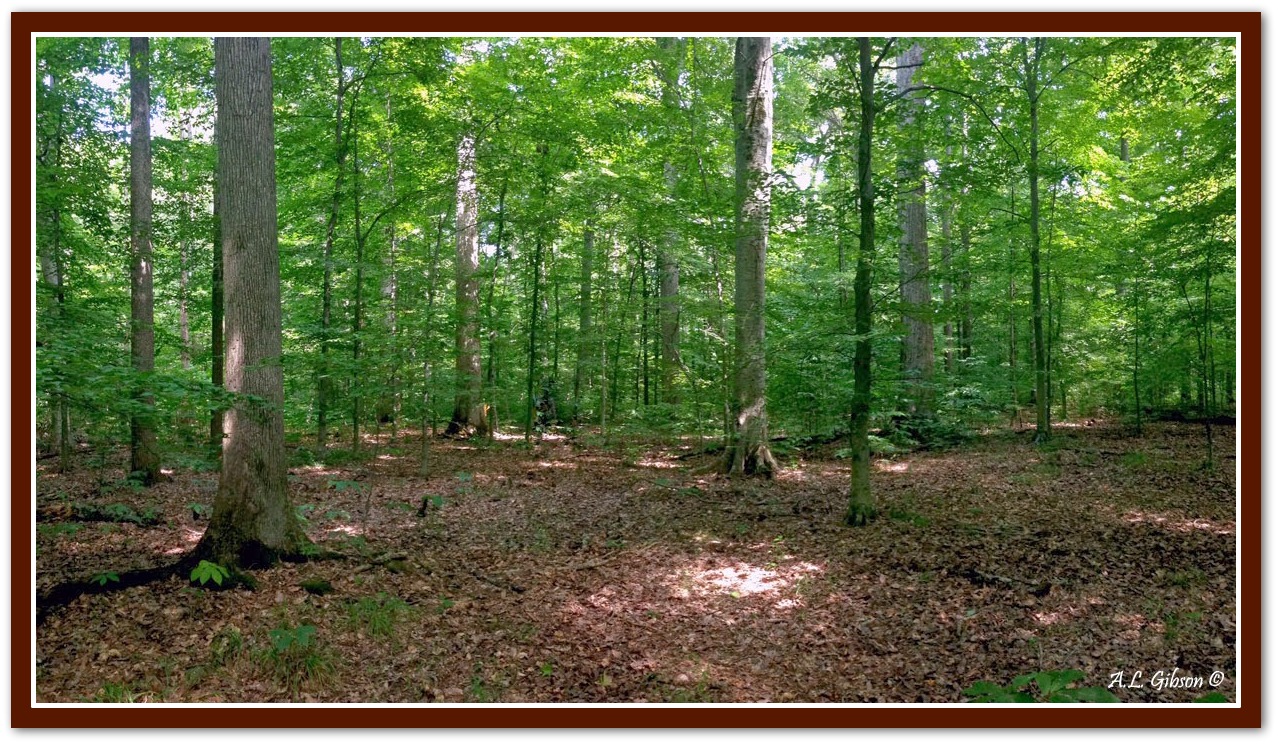

As a girl, she and her mother spent summers visiting Pearl’s grandparents in Chagrin Falls, Ohio, traveling from their home in New England to that “pleasant mid-western village with its shaded streets and comfortable Mid-Victorian homes,” as she wrote 60 years later.

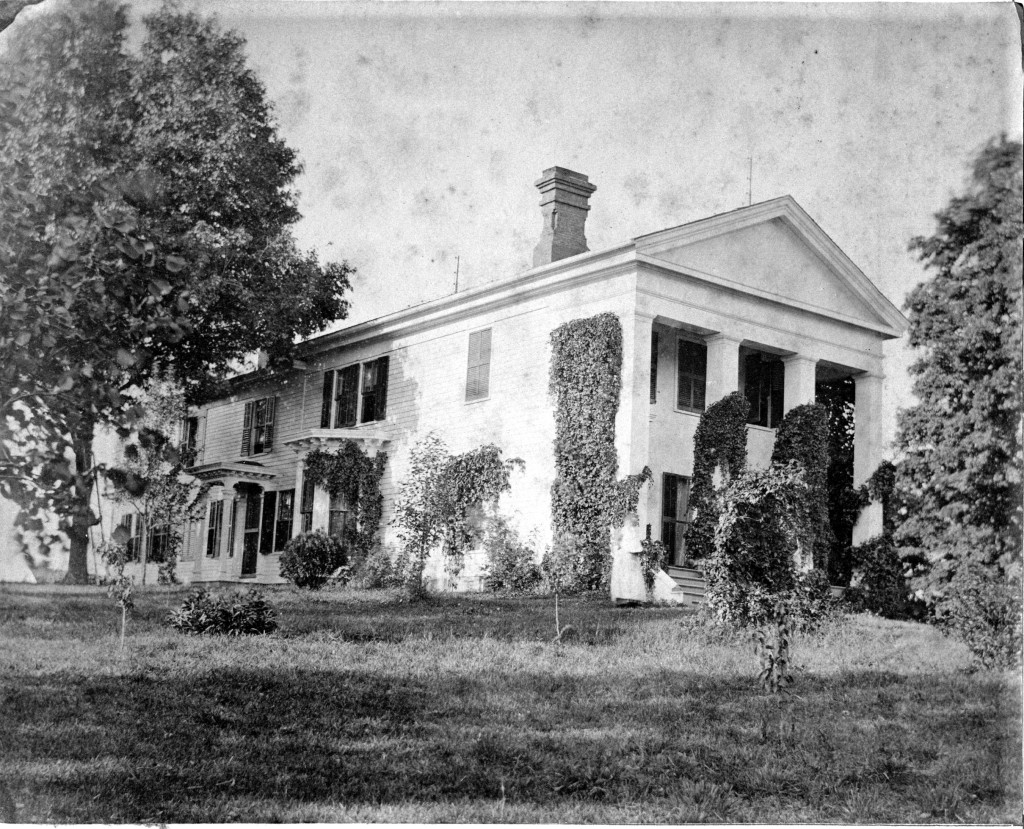

To Pearl, that was her true home. “A feeling of peace and security immediately enveloped me; a feeling I never remember having anywhere else.  Remembered delights and fascinating new experiences were before me, safely in the little white house or secure in the mansion on the hill.” They “were a gay and cheerful family,” she wrote.

Remembered delights and fascinating new experiences were before me, safely in the little white house or secure in the mansion on the hill.” They “were a gay and cheerful family,” she wrote.

Her two sets of grandparents were different from each other, but equally loved.

Her Grandparents Eggleston belonged to a world of “beauty and elegance, though bought at the expense of hard work and thrift. The great house with its huge rooms, its bay windows and fire places, porches and pantries, the stable and carriage house, the wash house and long arbor, the stone walks, so good for rope skipping; the hitching post carved to represent a small negro, guarding the stone block where one could gracefully enter or leave the waiting surrey (complete with the “fringe on top”).”

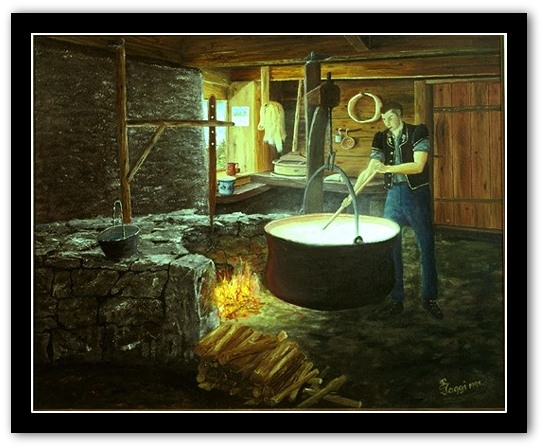

Her Grandparents Brown had a cheese factory, and a home that held “the greatest joy of all,” the “mysterious room, ‘grandfather’s room,’ the ‘holy of holies,’ reached by a steep, dark, winding and entirely suitable stairway,” and holding a vast collection of rocks, insects, and music boxes that Pearl could play with for hours.

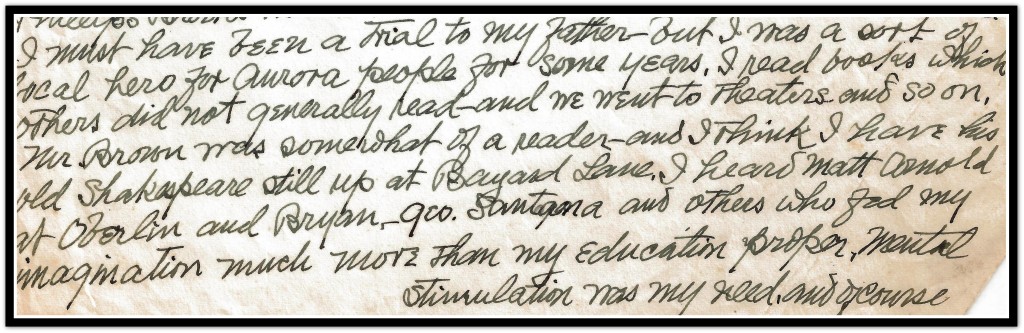

Later, in her teens, Pearl was enrolled in the Lake Erie College for Women in Painesville, Ohio. Her father wrote that, “She and Elizabeth Clark attended Painesville [Lake Erie] College. I drove them over from Chardon more than once — a pair of romantics who had their dreams.”

After their time there Pearl and her friend Elizabeth became two of the earliest American women to attend a regular four-year college, Oberlin.

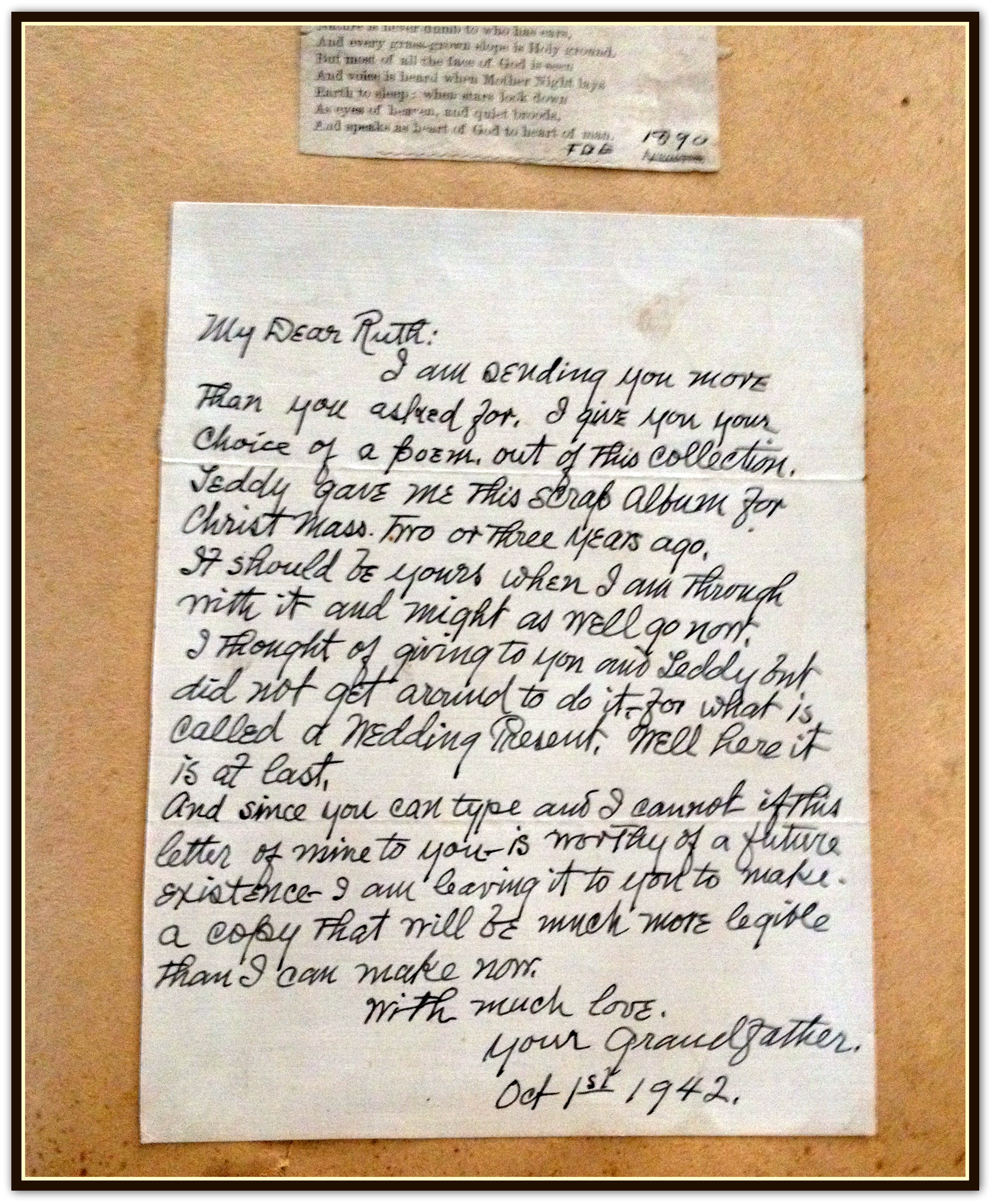

That is where they both met their husbands; first Pearl, who, her father wrote, “fell for Robert Berryman when she first went to Oberlin (1901). He was a track champion and as a scholar a prodigy. Later he made the only perfect score in the N.C.B. on Wall Street.” Then, “Elizabeth Clark married Waldo,” Robert’s younger brother, “soon after Pearl married Robert.”

“Pearl,” he continued, “would have liked nothing better than to settle down and be a professor’s wife.” But that was not to be. Robert was offered a “tenure track” teaching job at Ann Arbor, Michigan, but he had other plans.

The next chapter of Pearl Eggleston’s life will be published soon. To make sure you don’t miss the rest of the story, sign up to this blog at the top right of this page.

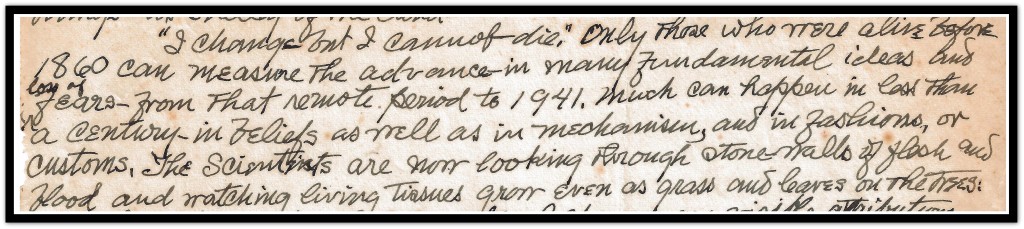

Darwin’s On the Origin of Species was published in 1859, yet it wasn’t until the 20th century that Darwin’s explanation of life was widely accepted by even the scientific community.

Darwin’s On the Origin of Species was published in 1859, yet it wasn’t until the 20th century that Darwin’s explanation of life was widely accepted by even the scientific community.

Two of the family’s five members died, my great-grandmother, Abigail Hickox Eggleston, and her young daughter, my great-grand aunt, Mary Eggleston.

Two of the family’s five members died, my great-grandmother, Abigail Hickox Eggleston, and her young daughter, my great-grand aunt, Mary Eggleston.

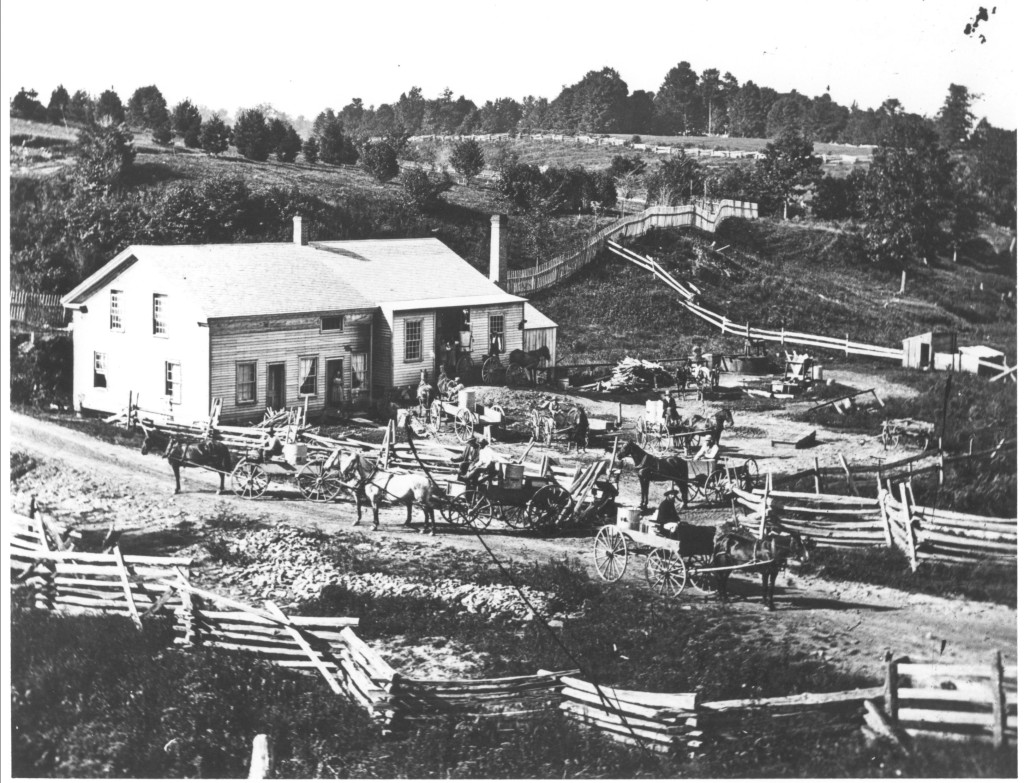

village founded by his forebears, who walked with their wagons hauled by teams of oxen from Connecticut across the rugged, nearly impenetrable Allegheny mountains and into the wild frontier of New Connecticut, as the Ohio territory was called, in 1807.

village founded by his forebears, who walked with their wagons hauled by teams of oxen from Connecticut across the rugged, nearly impenetrable Allegheny mountains and into the wild frontier of New Connecticut, as the Ohio territory was called, in 1807.

I don’t know Clinton’s reasons. Francis wrote simply that his father was “conservative in methods.”

I don’t know Clinton’s reasons. Francis wrote simply that his father was “conservative in methods.”

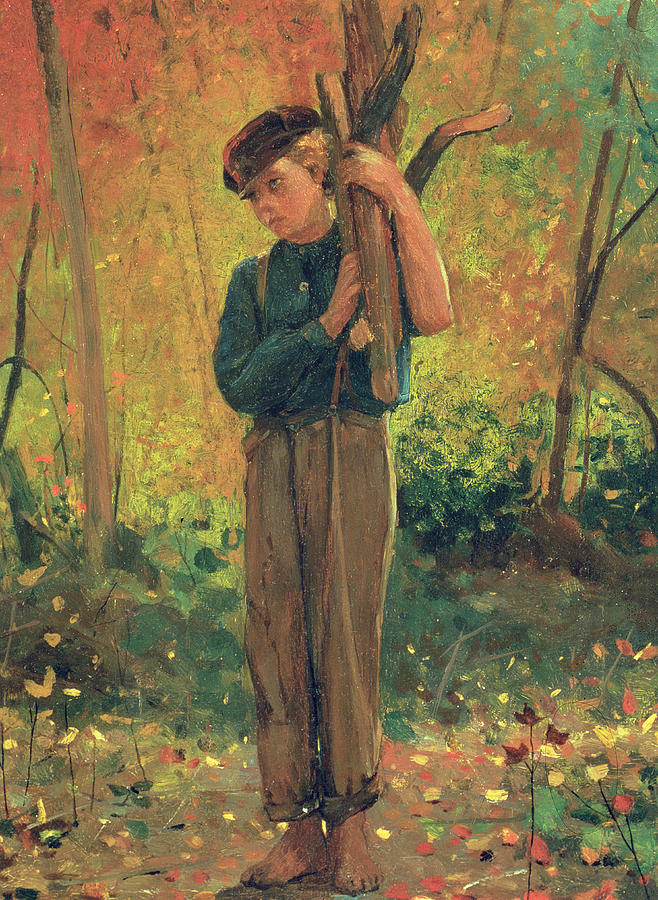

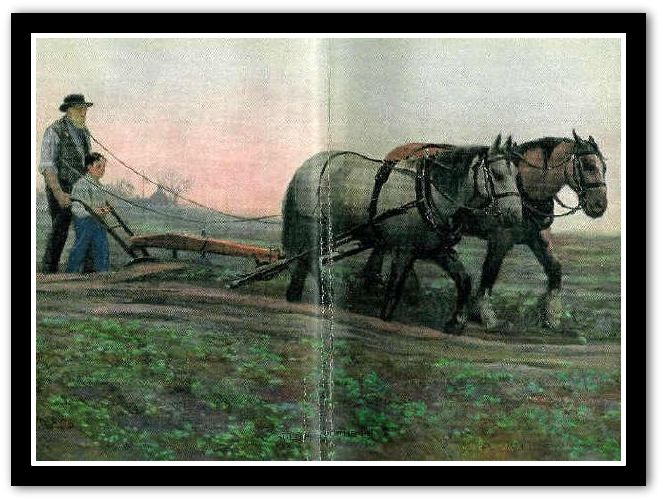

Just an adolescent, he was sent to split timber into “rails, 12 feet long and perhaps five inches square,” and to put his muscle behind “a great wood pile which was cut by horse-power and drag saw and split and corded by man and boy power.”

Just an adolescent, he was sent to split timber into “rails, 12 feet long and perhaps five inches square,” and to put his muscle behind “a great wood pile which was cut by horse-power and drag saw and split and corded by man and boy power.”

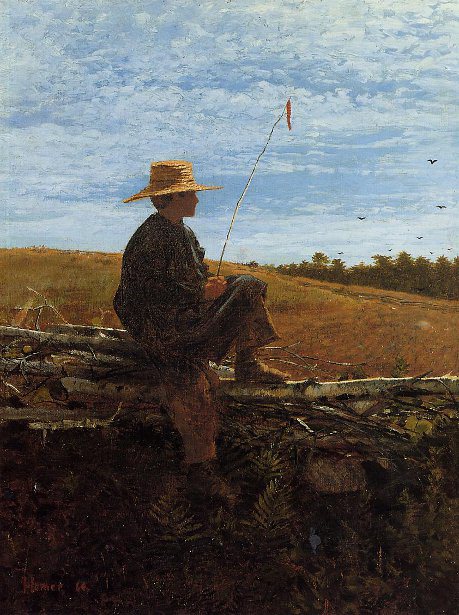

Francis helped produce all the chief products of the farm, which were milk, butter, cheese, and sugar; and to sow, grow, hoe, and harvest the field crops, which were hay and corn to feed the cows, and oats for the horses.

Francis helped produce all the chief products of the farm, which were milk, butter, cheese, and sugar; and to sow, grow, hoe, and harvest the field crops, which were hay and corn to feed the cows, and oats for the horses.

I began this story saying that Francis Eggleston often found himself in the wrong place, doing the wrong thing, or more specifically, the wrong thing for his temperament and interests.

I began this story saying that Francis Eggleston often found himself in the wrong place, doing the wrong thing, or more specifically, the wrong thing for his temperament and interests.

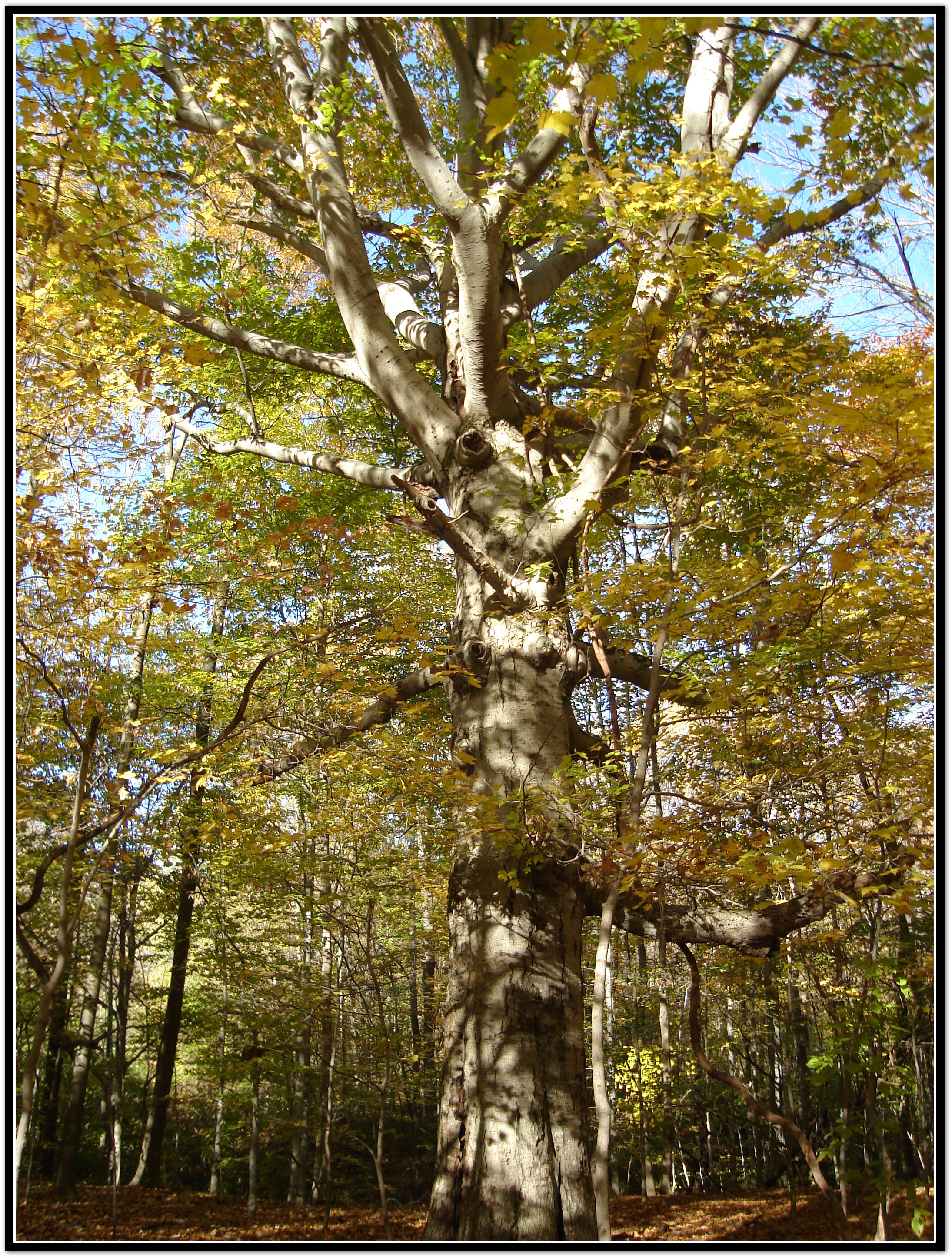

There were no chestnut trees, but they had hickory trees so big around that a full-grown man could not wrap his arms around them.

There were no chestnut trees, but they had hickory trees so big around that a full-grown man could not wrap his arms around them.